WATCH: Astronomers reveal hidden lives of early universe’s ultra-massive galaxies

An international team of astronomers — aided by a Big Island observatory atop Mauna Kea — uncovered multiple evolutionary paths for the universe’s most massive galaxies.

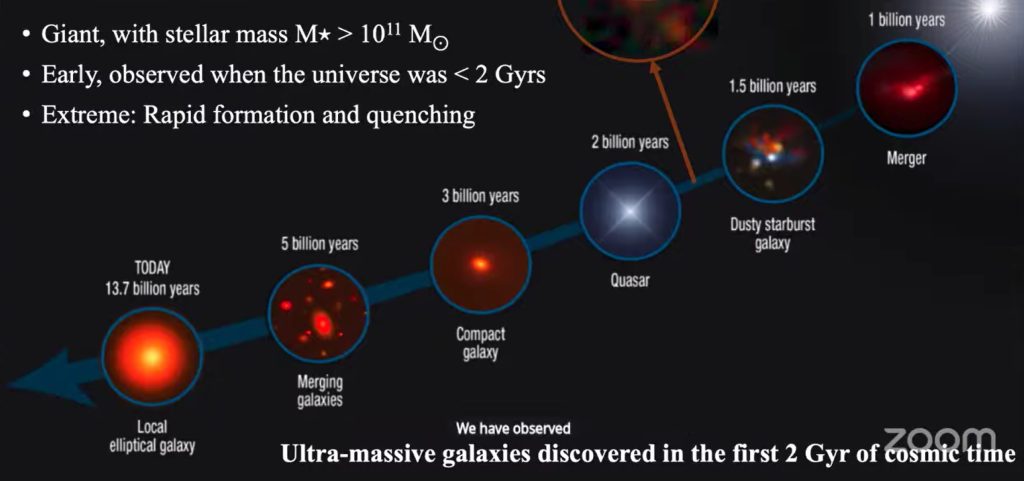

Observations of ultra-massive galaxies, each containing more than 100 billion stars, show that less than 2 billion years after the Big Bang, some already stopped forming stars and lost their dust while others continued forming stars hidden behind thick dust clouds.

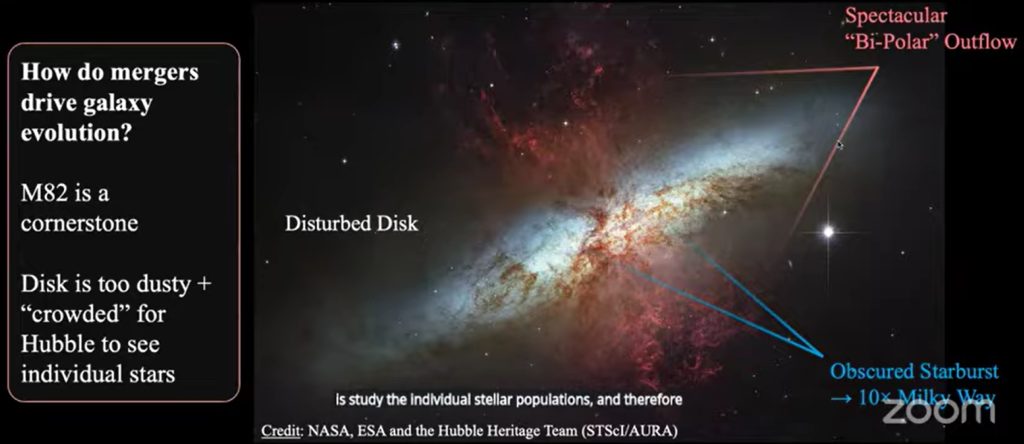

Distinguishing truly “dead” galaxies from those still forming stars has long been a challenge because dusty, star-forming galaxies can appear red and inactive — making the discovery of genuinely quiescent systems at such early times especially surprising.

“By combining multi-wavelength observations, we can tell which galaxies truly have limited ongoing star formation and which are still active but heavily hidden by dust,” said University of California, Riverside graduate student and lead author Wenjun Chang in a release about his team’s research. “Our far-infrared and [sub]millimeter measurements allow us to constrain how much dust these early massive galaxies contain.”

The study — led by Chang under the mentorship of University of California, Merced Vice Chancellor for Research, Innovation and Economic Development and physics professor Gillian Wilson — was presented during a media briefing Jan. 5 as part of the 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Phoenix, Ariz.

The findings come from the MAssive Galaxies at z ~ 3 NEar-infrared Survey, or MAGAZ3NE survey. It is a long-running collaboration using spectroscopy and multi-wavelength observations to investigate how the most massive galaxies in the universe formed and evolved.

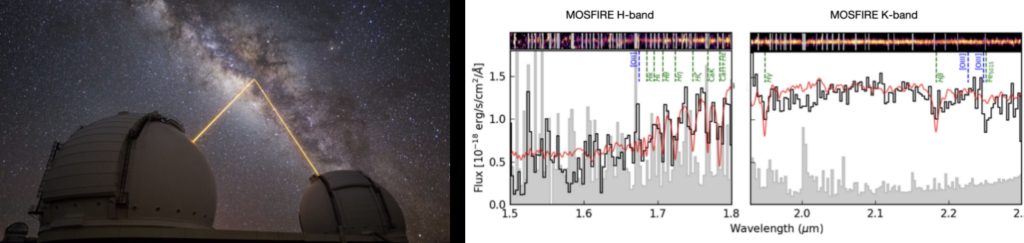

The team used more than 30 nights of the Big Island’s W. M. Keck Observatory spectroscopy obtained through the Multi-Object Spectrograph for Infrared Exploration, or MOSFIRE, instrument. That provided precise redshifts and stellar mass measurements needed to interpret multi-wavelength data.

Combining Keck Observatory optical data with longer-wavelength far-infrared and radio observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, or ALMA, and the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array enabled the researchers to test whether massive galaxies previously classified as quiescent were truly inactive.

Or were they instead hosting star formation or nuclear activity obscured at optical and near-infrared wavelengths?

“While optical and near-infrared data alone can severely underestimate obscured star formation in dusty massive galaxies, [Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array] probes far-infrared wavelengths, allowing improved constraints on the nature of these galaxies,” said University of California, Davis researcher Benjamin Forrest in the release.

Forrest played a central role in the development of the MAGAZ3NE survey and its multi-wavelength analysis of ultra-massive galaxies. He also led the proposal that resulted in many of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array observations used in this study.

“What is striking is not just that we can detect hidden activity, but that we see such diversity among galaxies with similar masses at the same epoch,” Wilson said in the release. “That tells us that the shutdown of star formation in the most massive galaxies was neither uniform nor simple, and it places important new constraints on our understanding of galaxy formation and evolution in the early Universe.”

Understanding how massive galaxies stop forming stars is key to explaining why today’s universe looks the way it does.

The team’s research helps clarify whether ultra-massive galaxies in the early universe are “dusty or dead” — their answer is not one or the other. The results show most of the ultra-massive galaxies studied are genuinely quiescent, indicating a rapid and efficient shutdown of star formation.

Several systems within this quiescent population are among the most dust-poor massive galaxies ever identified at these early cosmic times.

The remaining two galaxies exhibit residual dust emission, with one showing evidence for ongoing but heavily obscured star formation and the other caught in the process of quenching.

These results offer a rare glimpse into the diverse evolutionary paths taken by the universe’s most massive galaxies.

“What excites me most about this work is that we are able to study an extremely rare population in the universe by combining data from as many telescopes as possible,” Chang said. “By bringing together optical, near-infrared and far-infrared observations, we can build a much more complete picture of what ultra-massive galaxies really look like at these early cosmic times.”

Members of the MAGAZ3NE collaboration involved in this work include:

- Ian McConachie, postdoctoral researcher at University of Wisconsin–Madison.

- Professor Allison Noble of Arizona State University.

- Professor Tracy Webb of McGill University.

- Professor Adam Muzzin of York University, Canada.

- Professor Michael Cooper of University of California, Irvine.

- Professor Gabriela Canalizo of University of California, Riverside.

- Professor Danilo Marchesini of Tufts University.

- Percy Gomez, staff astronomer at W. M. Keck Observatory.

- Stephanie Urbano Stawinski of University of California, Santa Barbara.

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)