WATCH: ‘Superkilonova’; a star so nice, it explodes twice

Astronomers might have recently observed what could be a first-of-a-kind outer space oddball event — something that has only been hypothesized but never seen — and a Big Island observatory was part of the discovery.

A team of astronomers using a variety of telescopes — including W. M. Keck Observatory atop Mauna Kea — seem to have discovered a possible “Superkilonova,” or a kilonova spurred by a supernova.

Basically, it’s a star that exploded not once, but twice after a pair of dead stars called neutron stars are created by the supernova and then smash together.

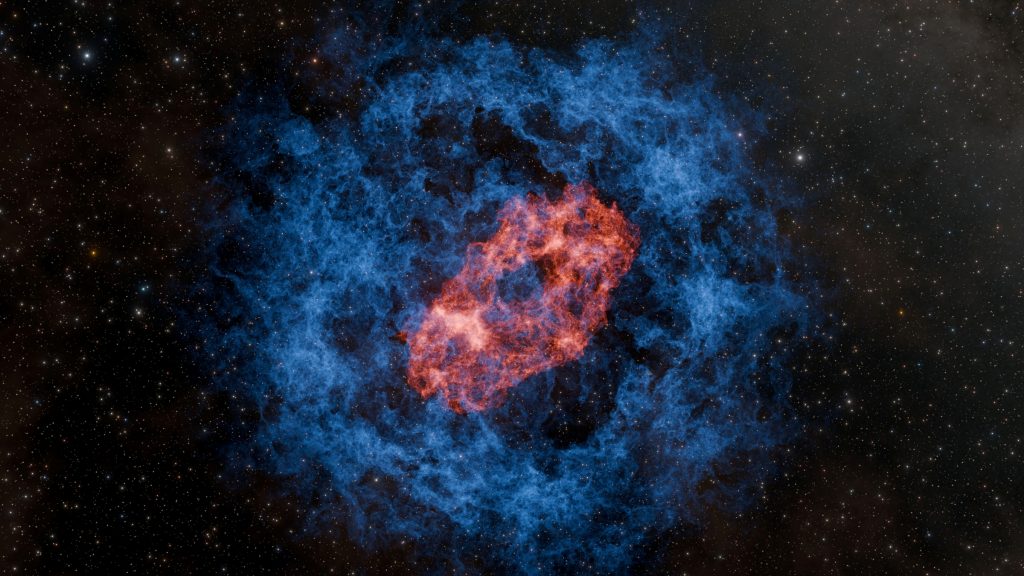

When the most massive stars reach the ends of their lives, they blow up in spectacular supernova explosions, seeding the universe with heavier elements such as carbon and iron.

Another type of explosion — the kilonova — occurs when a pair of dense neutron stars smash together, forging even heavier elements, such as gold and uranium.

The heavy elements created by these explosions are among the basic building blocks of stars and planets.

Only one kilonova has been unambiguously confirmed to date, a historic event known as GW170817 in 2017.

Two neutron stars smashed together, sending ripples in space-time known as gravitational waves, as well as light waves, across the cosmos.

The cosmic blast was detected in gravitational waves by National Science Foundation’s Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory and its European partner the Virgo gravitational-wave detector.

It was also detected in light waves by dozens of ground-based and space telescopes around the world.

The curious case of kilonova candidate AT2025ulz — the recently discovered blast — is complex and thought to have stemmed from a supernova blast that went off hours before, ultimately obscuring astronomers’ view and making the case even more complicated.

“At first, for about 3 days, the eruption looked just like the first kilonova in 2017,” said California Institute of Technology professor and Palomar Observatory Director Mansi Kasliwal in a release about the discovery. “Everybody was intensely trying to observe and analyze it, but then it started to look more like a supernova, and some astronomers lost interest.”

Not his team of astronomers.

Their study, led by California Institute of Technology, is published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

A new gravitational-wave signal was picked up in August by The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory and Virgo in Italy.

An alert was issued within minutes — containing a rough map of the source — signaling to researchers in the astronomical community that gravitational waves were registered from what appeared to be a merger between two objects — at least one of them being unusually tiny.

Kasliwal — after AT2025ulz was first identified by Zwicky Transient Facility at Palomar Observatory — coordinated with Keck Observatory staff astronomer Michael Lundquist to launch a rapid target of opportunity observation, a process that allows scientists to request immediate access for short-lived cosmic events.

Mansi’s request enabled the immediate spectroscopic follow-up using Keck’s low-resolution imaging spectrograph.

“Keck Observatory provided the imagery and spectroscopy via our low-resolution imaging spectrograph instrument to measure the host extinction and redshift of the galaxy, as well as looking at the spectroscopic evolution,” said Lundquist in the discovery release. “This highlights Keck Observatory’s target of opportunity capability to rapidly respond to transient alerts and deliver the spectroscopic data needed to explore potential multi-messenger associations.”

The observations confirmed that the eruption of light faded fast and glowed at red wavelengths — just as GW170817 did 8 years earlier.

In the case of the GW170817 kilonova, the red colors came from heavy elements such as gold; these atoms have more electron energy levels than lighter elements, so they block blue light but let red light pass through.

AT2025ulz then started to brighten again, turn blue and show hydrogen in its spectra, days after the initial blast, all signs of a supernova — specifically a “stripped-envelope, core-collapse” supernova — not a kilonova.

Supernovae from distant galaxies are generally not expected to generate enough gravitational waves to be detectable by LIGO and Virgo, whereas kilonovae can.

That led some astronomers to conclude that AT2025ulz was triggered by a typical, ho-hum supernova and not, in fact, related to the gravitational-wave signal.

Kasliwal said several clues tipped her off that something unusual took place.

Though AT2025ulz did not resemble the classic kilonova GW170817, it also did not look like an average supernova.

The LIGO–Virgo gravitational-wave data also revealed that at least one of the neutron stars in the merger was less massive than our sun, a hint that one or two small neutron stars might have merged to produce a kilonova.

It is possible, With LIGO and Virgo detecting at least one sub-solar neutron star, according to theories proposed by co-author Brian Metzger of Columbia University, that two newly formed neutron stars could have crashed into each other, erupting as a kilonova that sent gravitational waves rippling through the cosmos.

As the kilonova churned out heavy metals, it would have initially glowed in red light as Zwicky Transient Facility and other telescopes observed.

The expanding debris from the initial supernova blast would have obscured the astronomers’ view of the kilonova.

In other words, a supernova might have birthed twin baby neutron stars that then merged to make a kilonova.

“The only way theorists have come up with to birth sub-solar neutron stars is during the collapse of a very rapidly spinning star,” Metzger said in the discovery release. “If these ‘forbidden’ stars pair up and merge by emitting gravitational waves, it is possible that such an event would be accompanied by a supernova rather than be seen as a bare kilonova.”

While this theory is tantalizing and interesting to consider, the research team stresses that there is not enough evidence to make firm claims.

The only way to test the superkilonovae theory is to find more.

“Future kilonovae events may not look like GW170817 and may be mistaken for supernovae,” Kasliwal said. “We can look for new possibilities in data like this, but we do not know with certainty that we found a superkilonova.”

She added: “The event, nevertheless, is eye opening.”

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)