Kīlauea volcano’s rare eruption at summit, with 38 episodes and counting, hits 1-year anniversary

Katie Mulliken remembers her dad talking about the Pu‘u‘ō‘ō eruption from 1983 to 1986 in the East Rift Zone of Kīlauea. He told her living in Volcano Village, you would know when a lava fountaining episode started because you could hear the roaring of the volcano.

“I was so fascinated with that,” said Mulliken, who like her father, grew up on the Big Island. “Now, experiencing the episodes at the summit of Kīlauea — and I live in Volcano Village — it’s the same thing. You can hear the roaring from my house sometimes, or, you know, the night sky will light up once the fountaining episode has begun.”

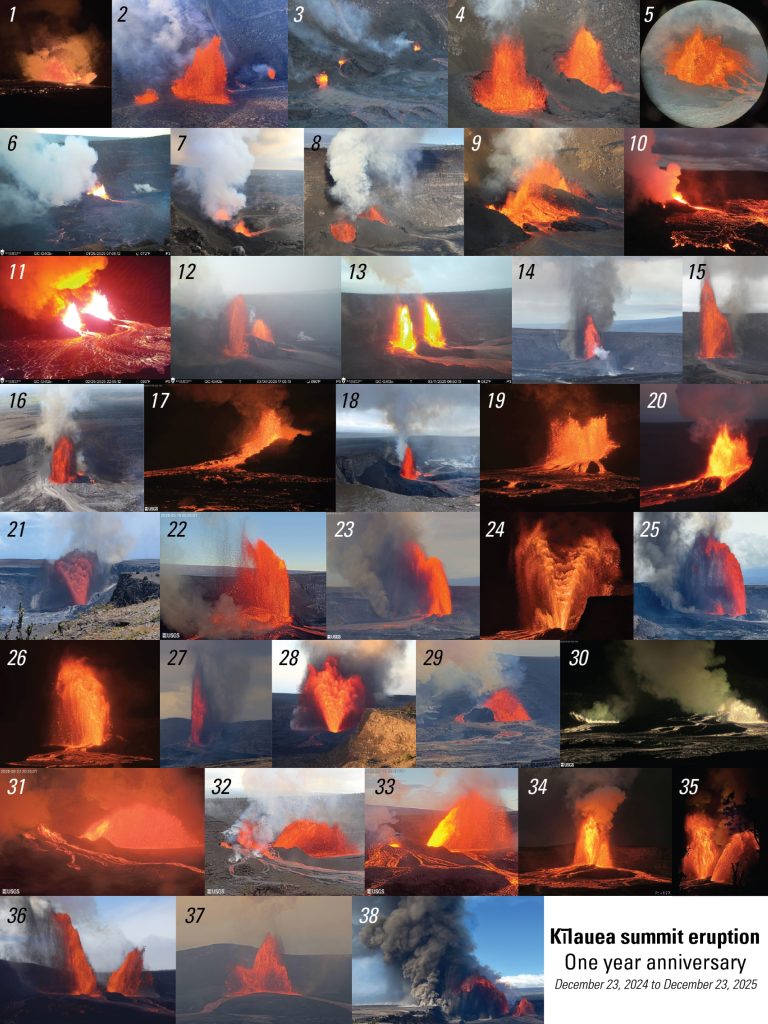

That has happened 38 times in the past year, and is expected to happen again soon.

Today, Dec. 23, marks the exact date 1 year ago that Kīlauea began a rare episodic eruption that had not happened for 40 years, since Mulliken’s dad heard the roaring from Pu‘u‘ō‘ō.

It is unlike previous summit eruptions, which produce constant lava flows for days, weeks or longer. This ongoing episodic eruption within Halema‘uma‘u Crater inside Kaluapele, the summit caldera of Kīlauea, is an uncommon type anywhere on the volcano, especially at the summit, said Mulliken, now a geologist at Hawaiian Volcano Observatory.

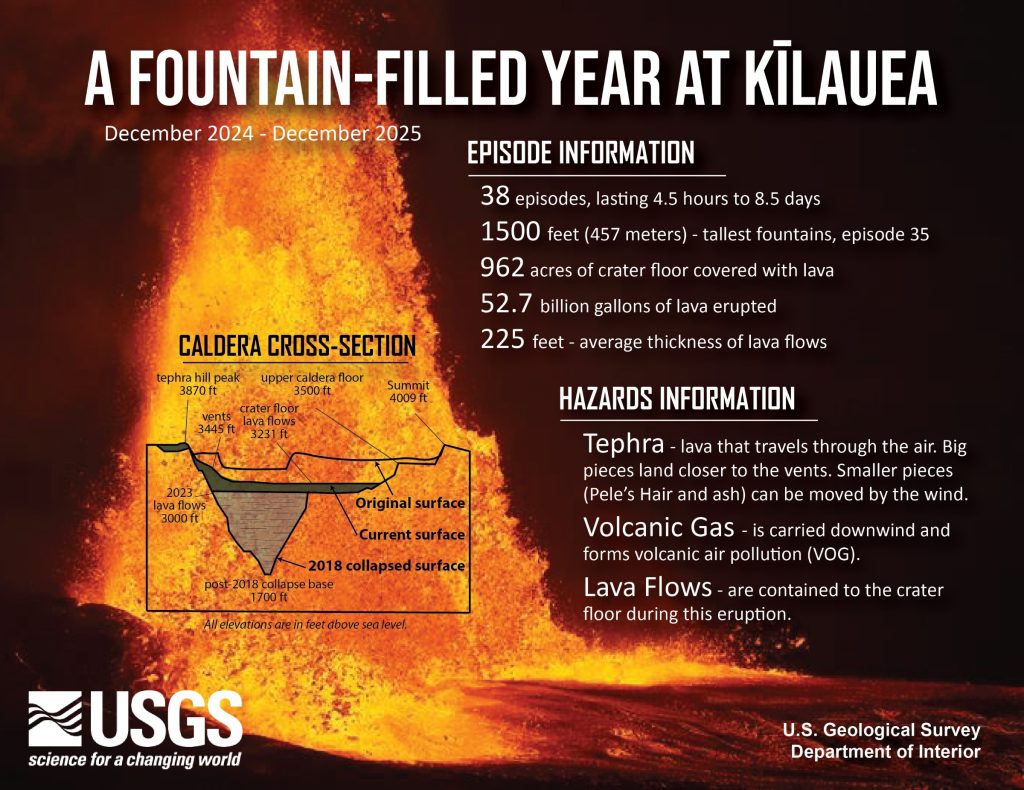

It has produced 38 eruptive episodes throughout the past year, all with dramatic high lava fountains, some as high as 1,500 feet, and molten rock flowing onto the crater floor and significantly changing its landscape.

Based on current rates of inflation at the summit, the 39th episode could be happening as you read this. Hawaiian Volcano Observatory forecast models indicate its onset between Dec. 23 and Dec. 26, with it most likely between Christmas Eve and Christmas Day.

There have only been four episodic eruptions on Kīlauea since documentation begin during the 1800s, including the current eruption.

The other three were:

- 1959 Kīlauea Iki eruption: It happened in the crater just north of the volcano’s caldera, lasting only about a month with 17 episodes and inclined lava fountains, including the highest lava fountains measured on Kīlauea to date at a massive 1,900 feet.

- Initial fountaining phase of the 1969-74 Maunaulu eruption. This occurred in the upper East Rift Zone, producing 12 episodes of inclined fountaining throughout nearly a year, reaching heights of nearly 1,800 feet.

- Early episodes of Puʻuʻōʻō from 1983-86: This happened in the middle East Rift Zone, with 44 lava fountaining episodes recorded throughout the 3-year period, reaching up to about 1,500 feet at times.

Ken Hon, scientist-in-charge at Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, said there has been an average of two to three eruptions a month during this episodic eruption.

“So that’s been exciting,” he said.

Thousands of visitors — from near and far — have flocked to Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park, where the eruption is confined. For those lucky enough to be there at the right time, they were treated to awesome views of sustained lava geysers.

Hon said “it’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity” to see lava fountains like those that have erupted during the past 12 months — and to be able to see them in an area that is so easy to access.

During Episode 35 on Oct. 17 and 18, the lava reached the top height so far of this ongoing eruption at nearly 1,500 feet.

These types of fountains are the distinguishing feature of Hawaiian volcanism — “what Hawaiian volcanoes are famous for.” Few other volcanoes around the world produce the large fountains of incandescent material.

“So being able to see it and have this opportunity to study them up close has been great,” Hon said. “Even more than that, we’re excited they’re occurring in a place where everyone can see it.”

This episodic eruption is the first to happen in the summit caldera since documentation began. It also is unique with two active vents.

Most often, eruptive activity will eventually center on one vent or fissure, such as what happened during the 2018 lower East Rift Zone eruption, during which Ahuʻailāʻau, the name given to Fissure 8, became the dominant source of lava activity.

While eruptive episodes have lasted days, including precursor and other activity, each fountaining episode has lasted between 5 and 40 hours, with pauses of 1 to 3 weeks.

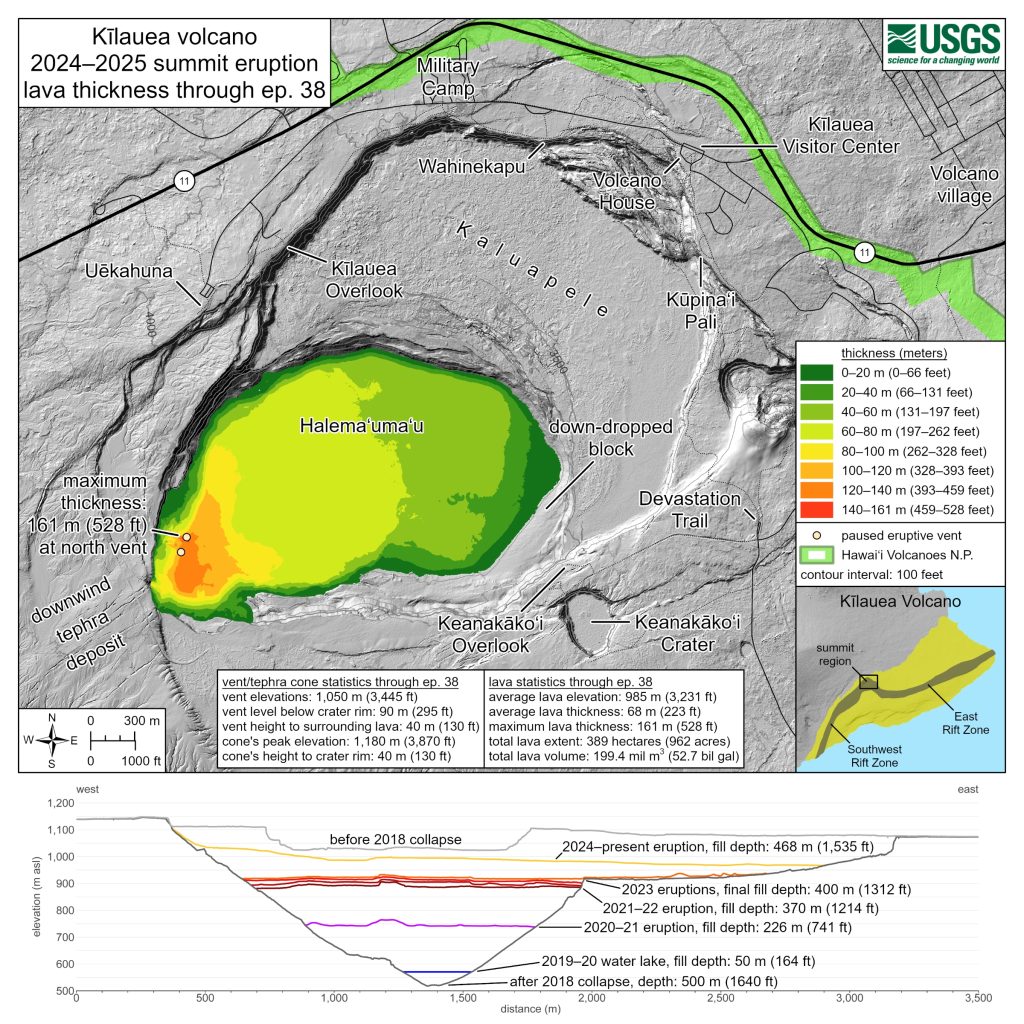

The repeated high fountaining has dramatically changed the landscape around the summit.

Tephra — volcanic material erupted during the fountaining — has blanketed the summit region to the southwest, extending for more than a mile of a closed area within Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park, covering pre-existing cracks and fault scarps.

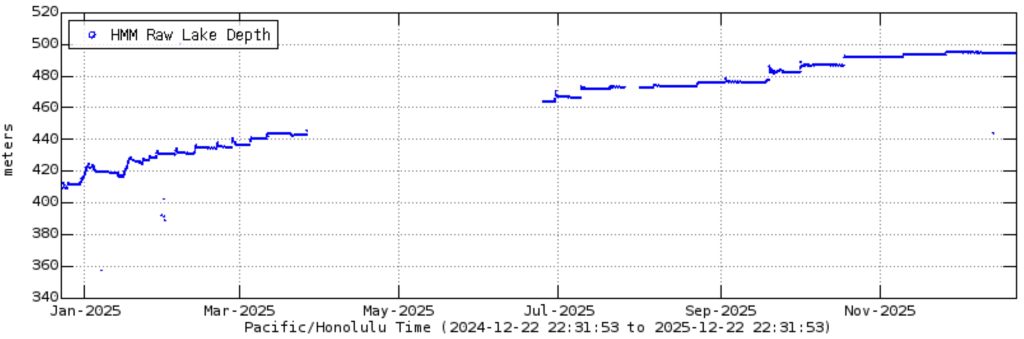

A new 140-foot hill now sits on the northwest rim of the caldera, and the floor of the caldera has raised 223 feet.

“The landscape has just been totally reshaped,” Mulliken said. “It’s such a stark contrast to what it used to look like before this eruption began. The area used to be full of cracks and crevices. The damaged road from the 2018 eruption was a very prominent feature out there.”

Now, with everything “totally blanketed by tephra,” she said it’s like a clean slate.

“All of the visual markers from that region, whether it was patches of vegetation or the damaged, cracked-up road, or this really big crack that marked the upper extent of the Southwest Rift Zone, all of that is totally buried now,” Mulliken said. “It’s just like this smooth landscape with nothing on the horizon.”

Every time she goes out there, the difference is “a little mind-boggling.”

The top of the two vents has reached an elevation of 3,445 feet, with the vents only 295 feet below the crater rim and just 130 feet taller than the surrounding lava lake. The tephra cone that has built up during the past year has a peak elevation of 3,870 feet.

To put that into perspective, Bayshore Towers on the north side of Hilo — the tallest building in the East Hawai’i community and on the Big Island — is about 135 feet tall. Furthermore, the summit of Kīlauea sits at an elevation of about 4,000 feet.

The eruption also has erupted a massive amount of molten rock.

About half of the caldera has been refilled by lava since the 2018 summit collapse after eruptions returned to the summit in 2020. This episodic eruption accounts for 25% of that.

“So, we still have quite a ways to go, but we’ve come pretty far,” Mulliken said about the caldera refilling.

Despite the awe-inspiring sights each eruptive episode has produced, they also have brought cause for concern.

Tephra — which includes the glass strands and particles called Pele’s hair — can be wafted downwind of the summit into communities several miles or more away. Places in Kaʻū, including Pāhala and as far as Ocean View, have seen accumulation of the volcanic material on the ground and other surfaces, even vehicles.

Tephra has even coated Highway 11 at times during the past year, making it more like a gravel road than a paved roadway.

There’s also volcanic gases, which can be blown even farther than tephra, including up the island chain to other places as far away as O‘ahu and even Kaua‘i. That includes vog — or volcanic fog — that is created when sulfur dioxide released from the volcano interacts with the atmosphere.

Vog can be dangerous for people with respiratory issues or even make life miserable for those without those types of problems. Volcanic gas emissions can get as high as 100,000 tonnes per day during an eruptive phase compared to about 1,000 when activity is paused.

Hawai’i Department of Health on Monday issued a warning for residents and visitors to protect themselves from poor air quality as lingering volcanic gases from the volcano continue to generate vog throughout the state.

Ashfall also has impacted communities and the national park during this eruption.

There is one other highlight of this eruption that keeps volcanic voyeurs and lava lookers as safe as watching from their homes and is related to how closely it is being monitored.

Hawaiian Volcano Observatory has a dense network of instruments constantly watching and providing data from Kīlauea’s summit — and for the first time that includes livestream webcams.

The webcams — now back up to three after a new camera was installed following the V3cam being covered by more than a couple dozen feet of tephra during Episode 38 — allow observatory scientists to monitor the eruption from different viewpoints around the caldera.

They also allow people around the world to watch the eruption in real-time.

“You can have the livestream on in your living room,” she said. “Anyone can do that. So many people comment on social media that they just keep it on [in] their living room as the episode is approaching.”

Hon said the livestreams have been a huge advance that came about because of several factors that made it affordable and doable.

“Everybody gets a chance to see all this stuff. It’s not just us,” he said. “Everyone can see it, which is really great.”

Hon added that as a volcano observatory, the entire staff takes “great pride” that they are able to share these events with people here and around the world.

Neither Hon nor Mulliken could predict how long everyone will be able to enjoy the ongoing eruption with its episodic nature and high lava fountains.

Activity at Kīlauea can change with the drop of a hat, but Mulliken said this eruption has been consistent and there are no signs of any changes coming soon.

There are several future possibilities, such as shifting into a long-term more effusive eruption, taking on a more usual manner, or the summit could transition back into the more periodic eruptions like what was experienced between 2020 and 2024.

“We can kind of narrow down the possibilities, but we can’t predict what’s going to happen,” Hon said.

Mulliken said the entire series of eruptions at Kīlauea and Mauna Loa since the 2018 lower East Rift Zone eruption and summit collapse, and even before, is why Hawai‘i is called the “best natural laboratory for studying volcanoes.”

“We have volcanoes that erupt in these diverse ways,” she said. “And just when you start to think that things are becoming routine, they start to change. So it really, I think, reinforces that point that we live in this really special place … .”

Hon said each eruption is an opportunity to learn more, and that learning gets reinvested in the observatory’s understanding of the volcano.

“That helps us interpret what’s next to keep the community informed, right?” he said. “It’s our feedback loop.”

At 10 a.m. on Dec. 23, a U.S. Geological Survey talk, “A Year of Lava Fountains at the Summit of Kīlauea,” will take place at the Steaming Bluff area of Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park for anyone who wants to learn more about the dynamic 1-year-old episodic eruption.

Those who attend should park in the Steam Vents parking lot and take the short walk out to the bluff. Overflow parking will be available at Kīlauea Visitor Center.

Mulliken said several other events and talk story sessions are planned during Volcano Awareness Month in January 2026 that will discuss the ongoing episodic eruption. A schedule of those programs can be found on the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory website.

The observatory also posted a special 1-year commemoration item on its website with additional information.

You can also contact Hawaiian Volcano Observatory via email at askHVO@usgs.gov with any questions.

Highlights from the past year include:

- Average lava elevation: 3,231 feet.

- Maximum lava thickness: 528 feet.

- Total lava extent: 962 acres, which translates to the same space encompassed by nearly 1,688 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

- Total lava volume erupted: 52.7 billion gallons. It equates to about 79,848 Olympic-sized swimming pools, or nearly 80,000 of Hilo’s Kawamoto Swim Stadium pools or Kailua-Kona’s Kona Community Aquatic Center pools.

- Episode pumping the most lava: Episode 3 at 13 million cubic meters, or just more than 3.4 billion gallons.

- Longest eruptive phase: Also Episode 3, which lasted 8 1/2 days from Dec. 26, 2024, to Jan. 3.

- Most recent: Episode 38, that lasted from 8:45 a.m. to 8:52 p.m. on Dec. 6, and pumped out 12.1 million cubic meters of lava, or almost 3.2 billion gallons.

- Highest lava fountains: Episode 35 at nearly 1,500 feet.

- Shortest lava geysers: Episode 30 on Aug. 6 at about 164 feet.

- Shortest high fountaining phase: 4.5 hours during Episode 20; however, the episode lasted longer with precursory low-level activity beginning a day and a half before.

- Longest pause between episodes: 17 days, between Episodes 23 and 33 and 34 and 35.

- Shortest pause: 1 day, between the initial eruption the early morning of Dec. 23, 2024, and Episode 2 that started at 8 a.m. Dec. 24, 2024.

- Most amount of deflation: About 30 microradians, which happened during Episode 3 and Episode 38, both of which had similar eruptive volumes, but on much different time scales. The have marked the beginning of fountaining episodes.

- Maximum amount of inflation: About 30 microradians. These have started as soon as eruptive episodes ended.

- Triple fountaining: While there have been several instances of double fountaining throughout the eruption; Episode 38 produced triple fountaining because of a division in the north vent creating separate fountains that erupted at the same time as the lava geyser from the south vent.

- Highest plume of volcanic gases and water vapor: 20,000 feet plus during Episode 38.

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)