El Niño ‘flavors’ help unravel past variability, future response to climate change

Looking to the past is often a way of understanding what the future will bring. A new study recently published in Nature Communications, does just that when it comes to the powerful force that is El Niño and how it responds as the Earth warms.

Scientists at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and University of Colorado Boulder have a clearer picture of El Niño patterns during more than 10,000 years after assessing the weather phenomenon’s so-called ‘flavors’ in historical records and model simulations. The research enables more accurate projection of future changes and impacts from El Niño, the primary factor affecting variability in water temperature and trade wind strength in the Pacific.

The new set of climate model simulations developed and analyzed by Christina Karamperidou, an associate professor of atmospheric sciences at the UH-Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology and lead author of the study, and co-author Pedro DiNezio, an associate professor at the UC Boulder, are the first to allow the study of changes in the frequency of El Niño flavors.

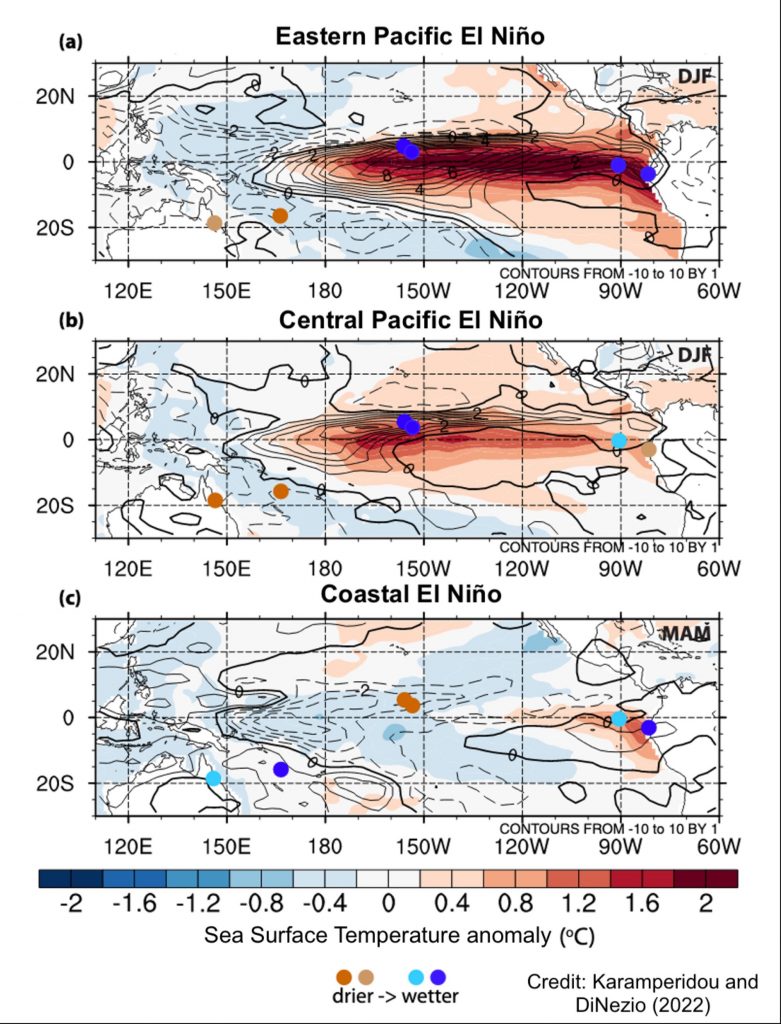

“We used a unique set of climate model simulations that span the Holocene, the past 12,000 years, and accounted for changes in the frequency of El Niño flavors, the three preferred locations in which the peak of warming during different El Niño events occur — eastern Pacific, central Pacific and coastal,” Karamperidou said in a press release. “Doing this allowed us to reconcile conflicting records of past El Niño behavior.”

This work offers new knowledge of how El Niño could respond to climate change and will help reduce uncertainties in global climate models, offering more accurate predictions of El Niño impacts.

El Niño is a warming of the ocean surface, or above-average sea surface temperatures, in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. The low-level surface winds, which normally blow from east to west along the equator, instead weaken or in some cases start blowing the other direction. Because of this, rainfall tends to become reduced over Indonesia while it increases over the tropical Pacific.

El Niño events have significant impacts on Hawai‘i’s rainfall, trade wind strength, the probability of hurricane formation and drought, and the type of El Niño event matters for these impacts.

“This information is important for water resource managers among others to better prepare for Hawai‘i regional climate,” Karamperidou said in the press release. “So it is imperative that we gain a better understanding of the mechanisms of these flavors, and also improve their representation in climate models and assess their projected changes under future climate conditions.”

Typically, researchers look for indicators of El Niño events in ancient, preserved material such as coral skeletons, Peruvian mollusk shells or lake sediment from the tropical Andes because locked within are indicators of past temperature and rainfall throughout the Pacific.

“However, depending on where the samples are taken from — eastern Pacific, central Pacific or near the South American coast — the frequency of El Niño events appears to exhibit different patterns,” Karamperidou said in the release. “Records from the eastern Pacific show an intensification of El Niño activity from early to late Holocene, while records from the central Pacific show highly variable El Niño throughout the Holocene.”

This allowed the researchers to test a hypothesis Karamperidou and her colleagues posed in 2015 — that paleoclimate records around the Pacific could be explained by changes in El Niño flavors.

“Indeed, we showed that eastern Pacific events have increased in frequency from early to late Holocene, while central Pacific and coastal events have decreased in frequency, resulting in changes in the hydroclimate in the tropical Pacific,” Karamperidou said in the press release. “Importantly, we showed that it is not only their frequency, but also the strength of their impact that changes, which is important for interpreting records of past climate.”

Additionally, this is the first study into the response of coastal El Niño events to climate changes. During these events, sea surface warming is confined off the coast of South America while the conditions in the rest of the Pacific basin are normal or colder than normal.

“These coastal events have supersized impacts with severe flooding and disasters in countries like Peru and Ecuador,” Karamperidou said in the press release. “In fact, we showed in another recent paper that even though these events are not felt around the globe like the more widely known eastern and central Pacific events, a better understanding of the mechanisms that drive them is essential for understanding the drivers of the other two flavors as well.”

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)