New analysis finds Hawaiʻi reef fish did not recover after aquarium collecting ended

A new analysis of state and federal monitoring data finds that yellow tang populations on Hawaiʻi reefs failed to recover — and in some cases declined — after commercial aquarium fish collecting ended, contradicting long-standing claims that the practice was sustainable.

Yellow tang is the most heavily collected reef fish for the aquarium pet trade outside Hawaiʻi, with millions of fish removed from Hawaiʻi’s reefs throughout the past two decades alone.

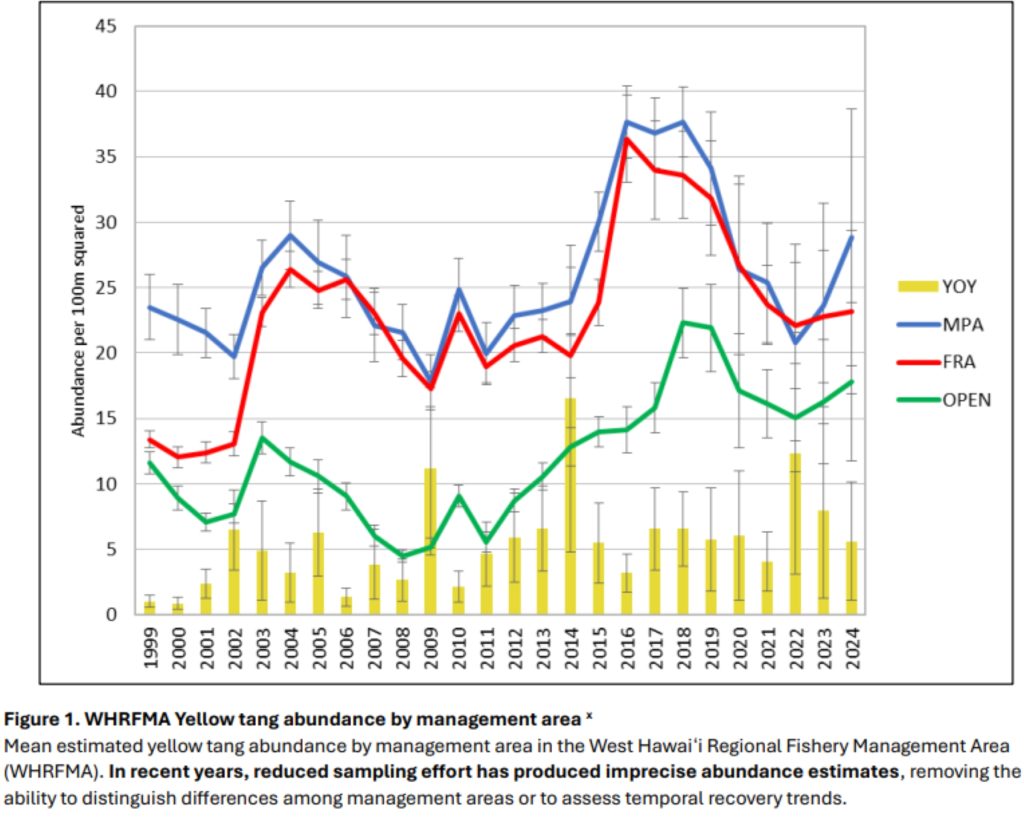

The analysis examines decades of monitoring data by Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources Division of Aquatic Resources and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, focusing on what happened after aquarium collecting stopped in 2017 and 2020, respectively, in waters off West Hawaiʻi on the Big Island and Oʻahu.

“Based on both past recovery and basic fish biology, yellow tang populations should have clearly doubled within a few years after collecting ended,” said Chaminade University professor of environmental studies/science Gail Grabowsky in a release about the new analysis. “Instead, the data show that recovery has not happened.”

What data show

- Yellow tang populations briefly increased after the 2017 closure in West Hawaiʻi waters, then fell back to roughly the same levels seen when collecting was still allowed.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data show yellow tang abundance in 2024 is lower than it was in 2019, when collecting was still occurring in O’ahu waters, where there were decades of heavy collecting pressure prior to it being stopped in 2020.

- Earlier history shows recovery is possible; after West Hawaiʻi protected areas were created in 1999, yellow tang populations doubled throughout about 4 years. That same recovery pattern did not occur after recent closures.

The analysis also highlights a major monitoring concern.

Division of Aquatic Resources in 2022 reduced its long-standing survey program from multiple survey rounds per year to just one, making recent data too limited to reliably detect changes in abundance.

Despite this uncertainty, none of the available data show population doubling.

“These findings are significant because aquarium collecting has repeatedly been justified by claims of sustainability and rapid reef fish recovery once harvesting stops,” said nonprofit For the Fishes Executive Director Rene Umberger in the release. “Those claims are not supported by what actually happened on Hawaiʻi reefs.”

The analysis is being released as state lawmakers consider legislation to permanently end commercial aquarium fish collecting in Hawaiʻi and as Division of Aquatic Resources seeks to issue new aquarium permits in West Hawaiʻi for the first time since 2017.

Contact Umberger at 808-283-7225 or via email at rene@forthefishes.org for additional information or with any questions.

Sponsored Content

Comments