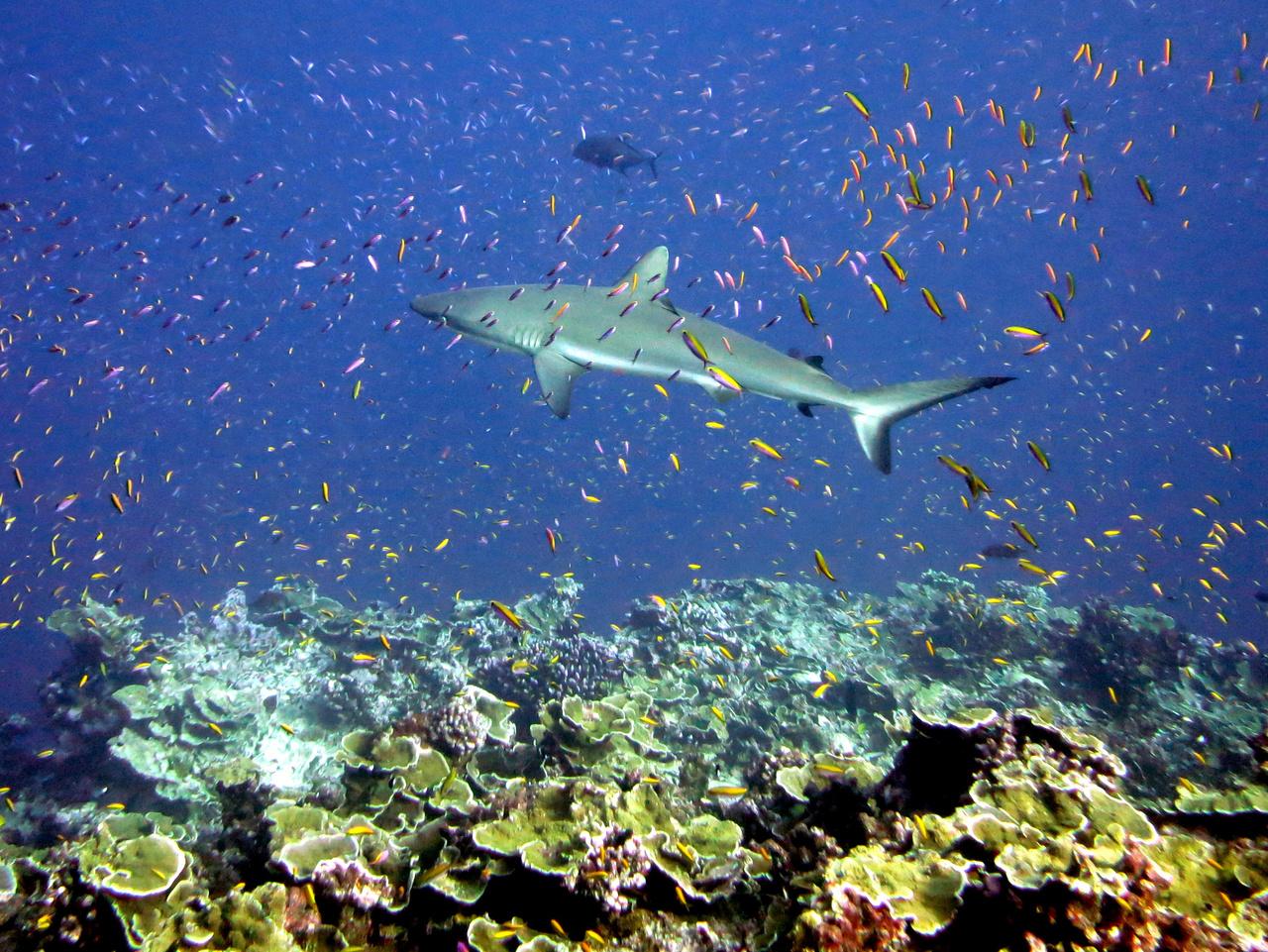

REPORT: Interventions May Save Coral Reefs

While the management of local and regional stressors threatening coral reefs is critical, these efforts on their own will not be enough in the face of global climate change, according to a new report released by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, said a University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa news release on Nov. 29, 2018.

The report co-authors, including Robert Richmond, research professor and director at Kewalo Marine Laboratory in the UH at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, explored the state of science on a variety of approaches to sustain coral reefs in rapidly deteriorating environmental conditions and assessed the interventions’ benefits and goals, feasibility, risks and infrastructure needs.

Worldwide, coral reefs have an estimated value of $1 trillion and nearly 500 million people depend on these vital ecosystems for wave protection, fisheries and tourism, cultural heritage, and food and livelihoods. Over the past few decades, however, about 50% of coral reefs have been lost and the rate of loss has increased with the impacts of global climate change.

“Quitting cigarettes is a positive step, but is insufficient if one already has lung cancer,” said Richmond. “The same is true for reefs–stopping stressors now is key, but only part of the solution. Interventions are needed and we are running out of time.”

This report is the first in a two-phase study evaluating the risks and benefits of implementing novel ecological, genetic and environmental interventions that could enhance the recovery and persistence of coral reefs. Included are 18 interventions across four broad categories.

Genetic and Reproductive Interventions provide an opportunity for increased selection and breeding of stress-tolerant traits that may improve the resilience of coral populations and species. Additional interventions include coral cryopreservation and genetic manipulation.

Physiological Interventions could influence the physiological responses of corals without changing their genomes. Pre-exposure of corals to high temperatures; manipulation of the symbiotic algae and microbiome; and additions of nutritional supplements, antibiotics, and antioxidants have been shown to confer resilience and improve disease resistance and overall condition.

Population and Community Interventions involve movement of individuals from one location to another could directly alter the composition of an entire population or communities of coral reefs. Relocation happens at different scales: from assisted gene flow to movement of coral to new ranges including across ocean basins.

Environmental Interventions employ a portfolio of local coordinated interventions to reduce light and heat stress include local cooling and shading. Reduction of ocean acidification in combination with biological and ecological interventions may also be necessary to ensure the persistence of coral reefs.

The questions to be considered, said Richmond, include: What is the goal: to protect and restore a reef, a species, habitat, an ecological function, an economic or cultural asset or a combination? How do we restore those conditions that support natural recovery and resilience?

In its final report, the committee will provide an environmental risk assessment and decision framework for evaluating the risks and benefits of implementing these interventions. Although reducing carbon emissions is an important mitigation strategy for addressing the impacts of climate change, even limiting human-induced surface warming to 2º Celsius is unlikely to save most coral reefs from the increased frequency and severity of bleaching events without further interventions, the report said.

“We can act to leave a vibrant legacy for the future,” encouraged Richmond. “This requires urgent interventions, not only to protect what’s left, but also to restore what has been lost.”

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)