Volcano Watch: What do small earthquakes beneath Kīlauea summit mean for the ongoing eruption?

Since the current eruption began on the night of Dec. 23, 2024, the Kīlauea summit region has been remarkably quiet from an earthquake standpoint.

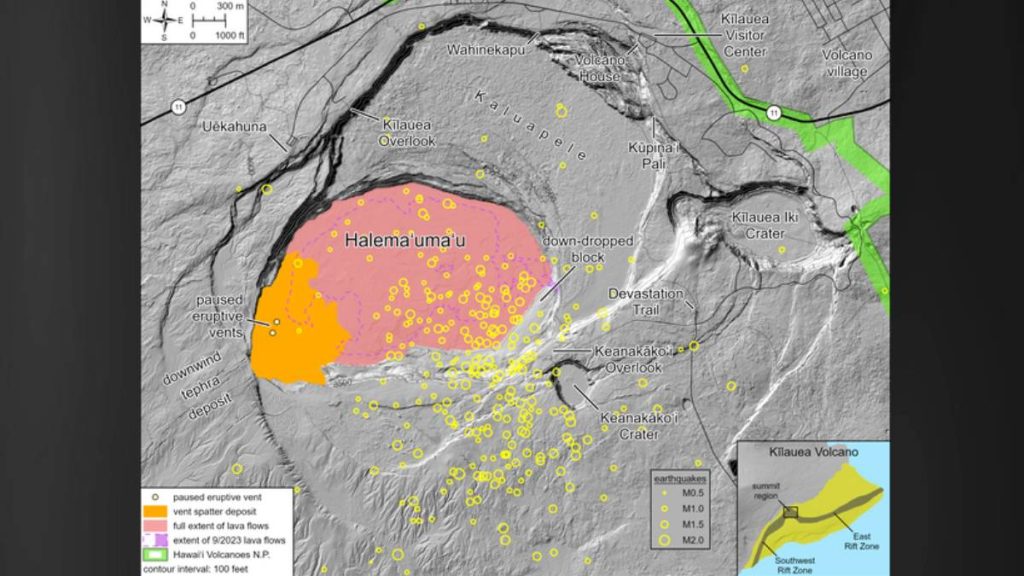

But since the end of episode 40 on the evening of Jan. 12, nearly a dozen small earthquake swarms have occurred involving earthquakes 1 to 2.5 miles beneath Halemaʻumaʻu and the summit caldera of Kīlauea.

Each swarm was brief, lasting around half an hour, and consisted of tiny earthquakes, usually smaller than magnitude 1.5. Up to 25 earthquakes were detected during one of the swarms, but the actual number of earthquakes was more because many earthquakes were too small to locate precisely.

The only other time earthquakes occurred like this was when a small intrusion formed in the southwest wall of the crater during episode 30 on Aug. 6, preceding a fissure that erupted briefly.

Summit deformation as seen in changes in ground tilt (slope) around the summit is broadly due to changes in pressurization of the shallow Halemaʻumaʻu magma chamber. During fountaining, the magma chamber deflates as lava is erupted, while during pauses it steadily reinflates.

In addition to this cyclic behavior, GPS data suggested that the Halemaʻumaʻu reservoir was slowly repressurizing to a higher level with each episode, and that the system was slowly gaining back pressure that was lost during the initial strong deflation of the first four episodes of the current eruption.

Kīlauea summit magma system is in a complex balance of magmatic pressure and strength of the surrounding rocks. These small earthquake swarms since the end of episode 40 indicate a small shift in this balance.

Most of the swarms have been accompanied by small and brief deflationary signals in the tilt recorded on tiltmeters in Kīlauea summit region. Outside of the swarms, overall inflationary tilt is continuing in a typical pattern for episode pauses.

These swarms may be our first sign of changes in the ongoing eruption, though it is not yet clear exactly what that change will look like. Earthquake locations during the swarms are widely dispersed, and do not delineate a specific pathway.

Deformation patterns during the swarms show that a small amount of magma was possibly being transferred from the Halemaʻumaʻu magma chamber, likely into surrounding cracks.

In contrast, when a new eruptive fissure formed in the southwest wall of Halemaʻumaʻu during episode 30 on Aug. 6, earthquakes were tightly clustered along the path that magma made to the surface and changes in the patterns of summit region ground deformation clearly indicated that magma had intruded into shallow depths along a well-defined crack.

We can look to past episodic eruptions for clues as to how any potential changes in the current eruption could unfold.

The fountaining phases at the start of the Puʻuʻōʻō (1983–86) and Maunaulu (1969) eruptions on the East Rift Zone of Kīlauea transitioned into different styles of activity because of accumulated pressure.

At Puʻuʻōʻō, fissures reopened on either side of the vent, while at Maunaulu, the eruption stalled and the vent collapsed though the eruption resumed at new fissures nearby months later. Likewise, pressure is continuing to grow in the shallow Halemaʻumaʻu chamber, and likely responsible for some of these subtle recent changes.

The Kīlauea Iki eruption in 1959 is not very comparable and occurred under unique conditions that are summarized in a separate “Volcano Watch” article.

As these past episodic eruptions demonstrate, the episodic fountaining nature of the ongoing eruption in Halemaʻumaʻu could eventually change. Under current conditions, the most likely change could be that the vents breakdown and begin to erupt lava more continuously in Halemaʻumaʻu, or lava could form a new vent in the summit area or upper Southwest Rift Zone. While it is possible that magma may migrate into the East Rift Zone, it is the least likely scenario.

The USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory will continue to closely monitor Kīlauea (and Mauna Loa, too).

Editor’s Note: Volcano Watch is written by staff at Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. The articles over the past two weeks have described past episodic lava fountaining eruptions at Kīlauea Iki (1959) and Maunaulu (1969). Next week, Volcano Watch will continue this series with a summary of the most recent past episodic eruption at Kīlauea. Why? Because past eruptions can provide clues about how the ongoing episodic eruption in Halemaʻumaʻu might progress or change.

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)