‘Forever chemicals’ could increase liver disease risk in adolescents

A new study co-led by University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and Southern California Superfund Research and Training Program for PFAS Assessment, Remediation and Prevention Center, or ShARP Center, linked certain common “forever chemicals” to a higher risk of liver disease in adolescents.

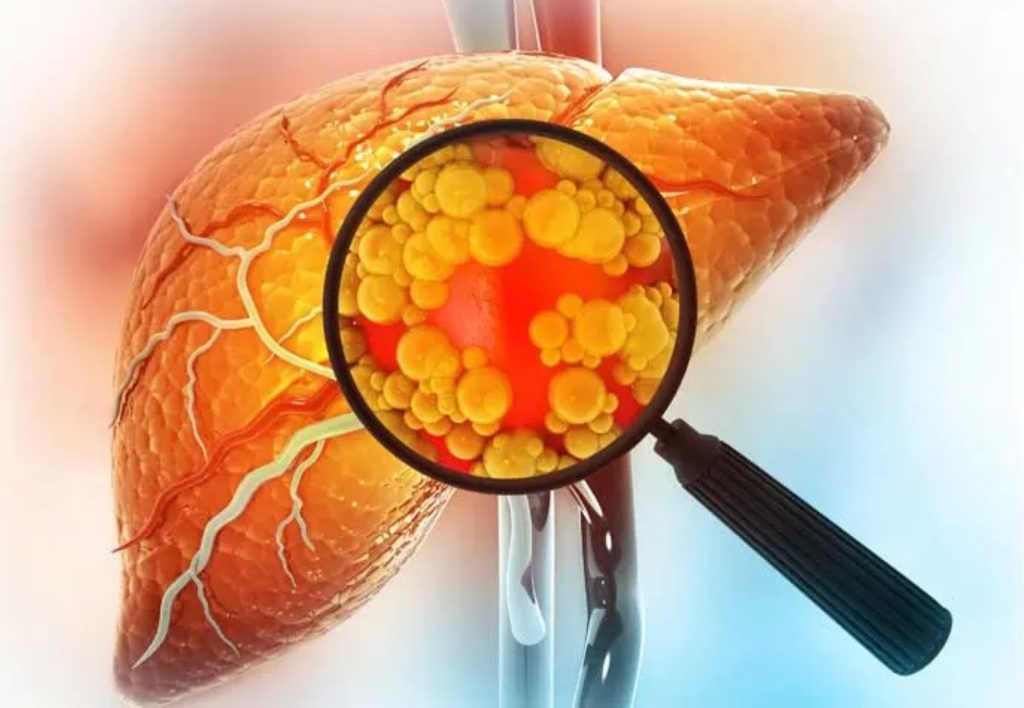

These synthetic compounds — known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS — could as much as triple the chances adolescents develop a liver condition called metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, formerly known as fatty liver disease.

The findings were published in the journal Environmental Research.

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease affects about 10% of children and up to 40% of children with obesity.

It is a chronic condition that doesn’t always have telltale symptoms; although, some patients experience fatigue, discomfort and abdominal pain. The disease increases longterm risk for Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, advanced liver injury, cirrhosis and even liver cancer.

“[Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease] can progress silently for years before causing serious health problems,” said Lida Chatzi in a release about the new study.

Chatzi is a professor of population and public health sciences and pediatrics and the director of the Southern California Superfund Research and Training Program for PFAS Assessment, Remediation and Prevention Center, a national center funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences to investigate per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances health impacts, advance cleanup technologies and support affected communities.

“When liver fat starts accumulating in adolescence, it may set the stage for a lifetime of metabolic and liver health challenges,” Chatzi said. “If we reduce [per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances] exposure early, we may help prevent liver disease later. That’s a powerful public-health opportunity.”

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances are manufactured chemicals used in nonstick cookware, stain- and water-repellent fabrics, food packaging and some cleaning products. They persist in the environment and accumulate in the body with time.

More than 99% of people in the United States have measurable per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in their blood, and at least one per- or polyfluoroalkyl substance is present in roughly half of U.S. drinking water supplies.

“Adolescents are particularly more vulnerable to the health effects of PFAS as it is a critical period of development and growth,” said the study’s first and corresponding author Shiwen “Sherlock” Li in the release. “In addition to liver disease, [Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances] exposure has been associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, including several types of cancer.”

Li is an assistant professor of public health sciences at University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Thompson School of Social Work and Public Health.

The research examined 284 Southern California adolescents and young adults from two University of Southern California longitudinal studies. The participants were already at higher metabolic risk because their parents had Type 2 diabetes or were overweight.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances levels were measured through blood tests, and liver fat was assessed using magnetic resonance imaging.

Higher blood levels of two common per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances — perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, and perfluoroheptanoic acid, or PFHpA — were linked to a greater likelihood of MASLD. Adolescents with twice as much PFOA in their blood were nearly three times more likely to have metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease.

The risk was even greater for those with a genetic variant (PNPLA3 GG) known to influence liver fat. In young adults, smoking further amplified PFAS-related liver impacts.

“These findings suggest that [per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances] exposures, genetics and lifestyle factors work together to influence who has greater risk of developing [metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease] as a function of your life stage,” said assistant professor of population and public health sciences at the Keck School of Medicine Max Aung in the release. “Understanding gene and environment interactions can help advance precision environmental health for [metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease].”

Li noted that this study is the first to examine per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in children using gold-standard diagnostic criteria, and the first to explore how genetic and lifestyle factors could interact with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances exposure.

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease also became more common as adolescents grew older, adding to evidence that puberty and early adulthood may increase susceptibility to environmental exposures.

The study builds on recent University of Southern California research showing for adolescents undergoing bariatric surgery to manage obesity, a per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance known as PFHpA is linked to more severe liver disease, including inflammation and scarring of connective tissue called fibrosis.

“Taken together, the two studies show that PFAS exposures not only disrupt liver biology but also translate into real liver disease risk in youth,” Chatzi said. “Adolescence seems to be a critical window of susceptibility, suggesting [per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances] exposure might matter most when the liver is still developing.”

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)