Attack on Pearl Harbor from Japanese fighter pilots, prisoners of war points of view

Just before 8 a.m. — 84 years ago today — Dec. 7, 1941, nearly 200 Imperial Japanese Navy aircraft took the United States and O‘ahu by surprise when they attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor.

Images of black smoke billowing from and above Pearl Harbor, engulfing structures and vessels; wreckage littering the land and sea at Ford Island. These scenes are ubiquitous with the “date which will live in infamy” and ultimately thrust the United States into World War II.

It was a devastating attack.

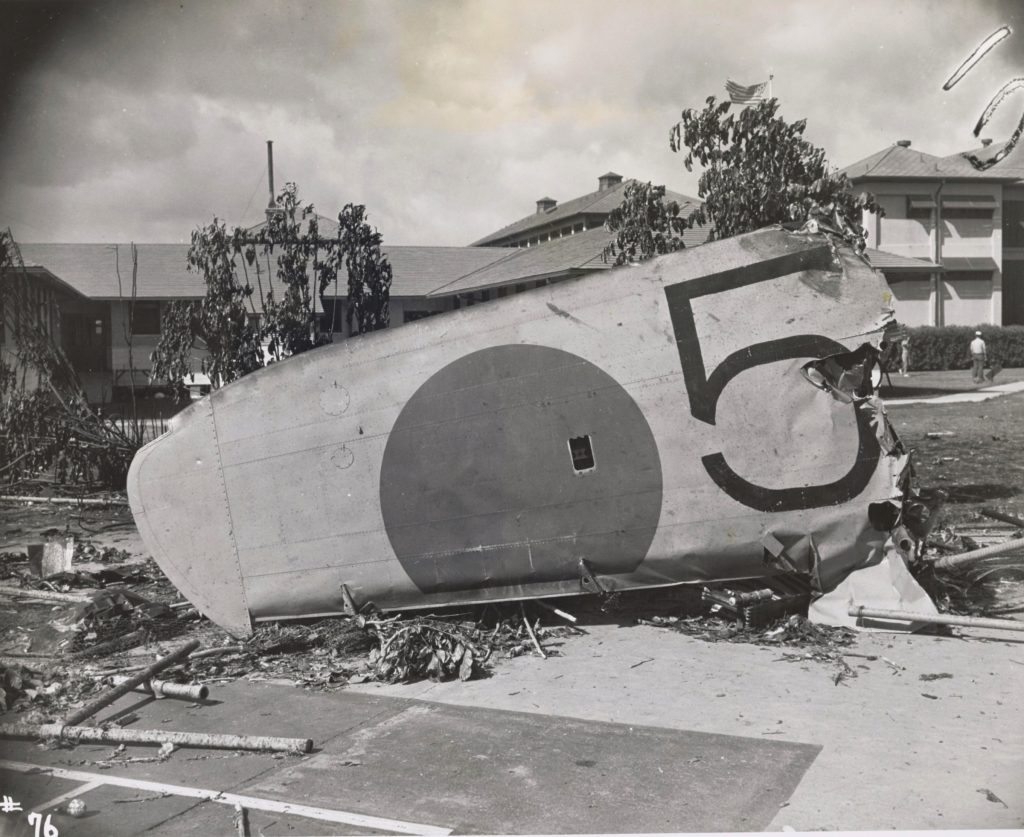

But less common are images captured by the Japanese fighter pilots themselves, found in planes or taken from prisoners of war.

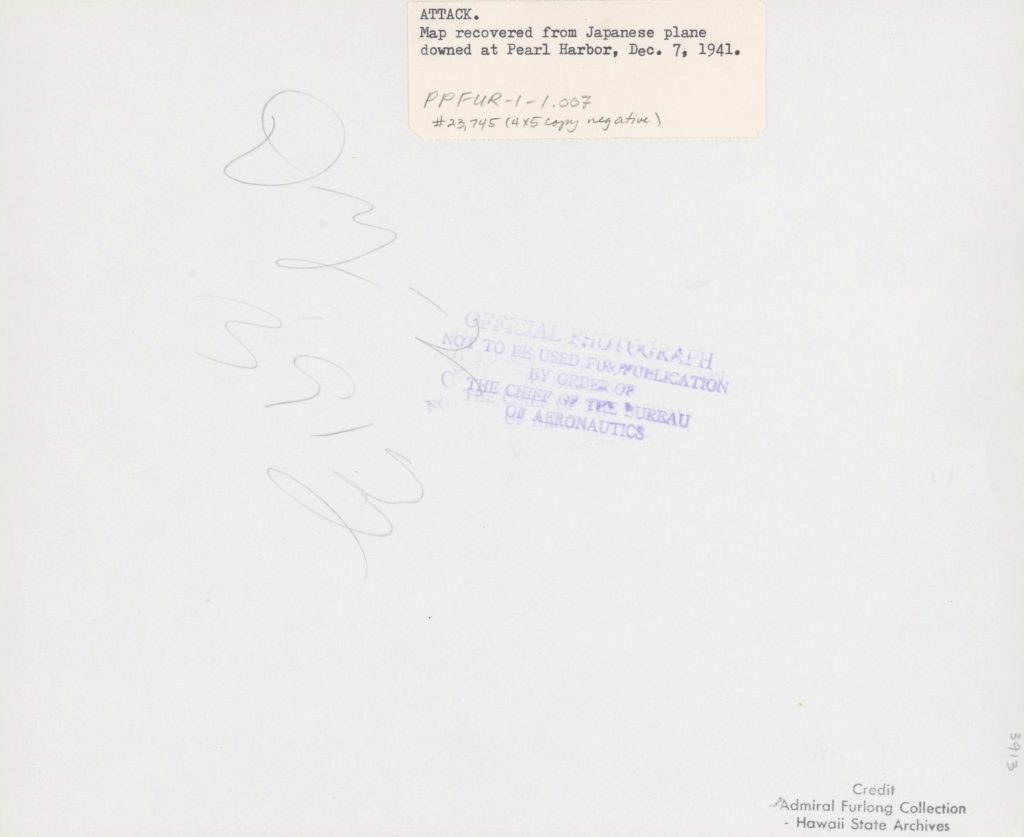

The U.S. military kept the photos close for decades; some marked on the back as “Not To Be Used For Publication.” They were kept in the dark, not seen publicly for decades while under military ownership.

It wasn’t until the images were donated to Hawaiʻi State Archives that they became public. They were then digitized and posted on the state archives website, making them even more accessible to see and use.

Eight of the nine U.S. battleships at anchor in the harbor were sunk or heavily damaged — including the USS Arizona, which saw the highest casualties from the attack as a total of 1,177 crew members died, more than 900 of them still entombed in the sunken vessel.

The battleship and its now silent crew still suffer from the attack’s ramifications.

Significant portions of two World War II-era mooring platforms — which could have collapsed through the ship’s decks because of their weight — were only just removed in October, relieving stress on the war grave and now memorial site, helping preserve the historic vessel.

More than 150 U.S. aircraft were destroyed in the Japanese sneak attack, and on a single day, more than 2,400 U.S. military service people were killed; another 1,200 wounded. Nearly 70 civilians also were killed in the strike.

Just a day later, then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the declaration of war against Japan mere hours after a nearly unanimous vote by Congress to officially enter the conflict.

Hawaiʻi State Archives wanted to highlight some of those photos recovered from the Japanese perspective as a way to mark the somber 84th anniversary of the attack, which is today, Dec. 7, and allow the public to better understand the events of that day.

There are a couple of aerial photographs taken from a plane during the Dec. 7, 1941, attack. Both photos show Ford Island in the foreground and a row of battleships. You can see them here and here.

Another photo from a “captured Japanese” pilot shows military members saluting a plane taking off from a tarmac, with the Japanese flag flying above them.

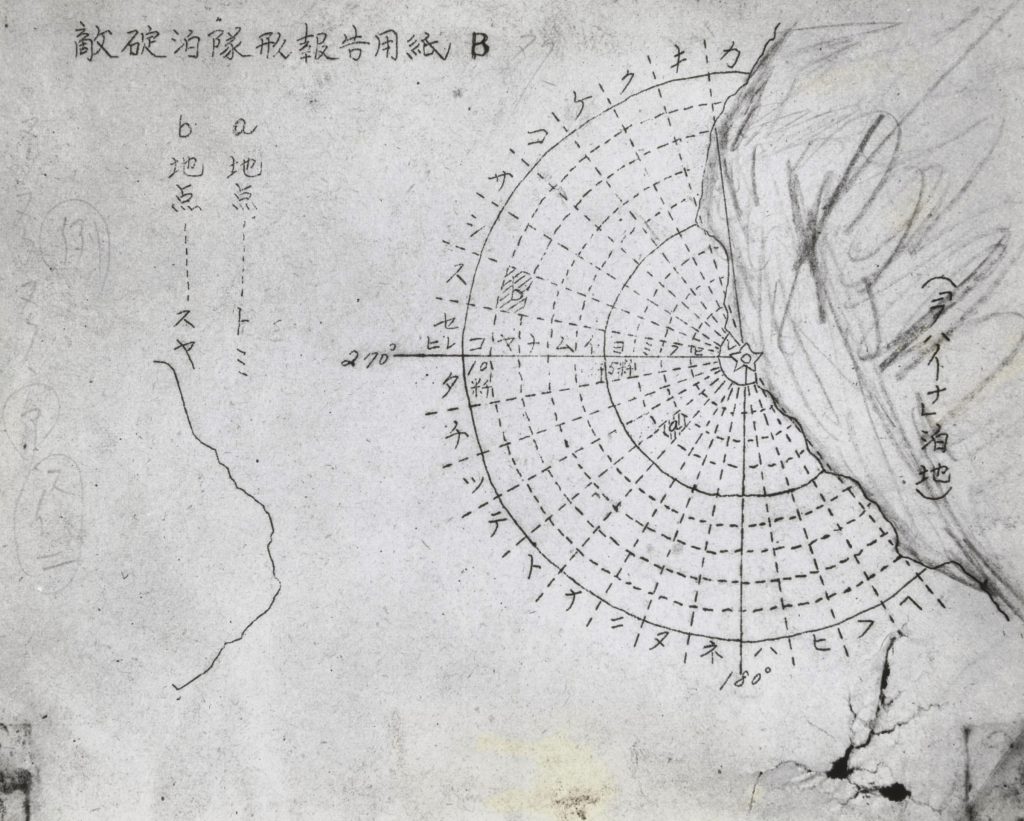

Other pictures document items taken from downed Japanese planes.

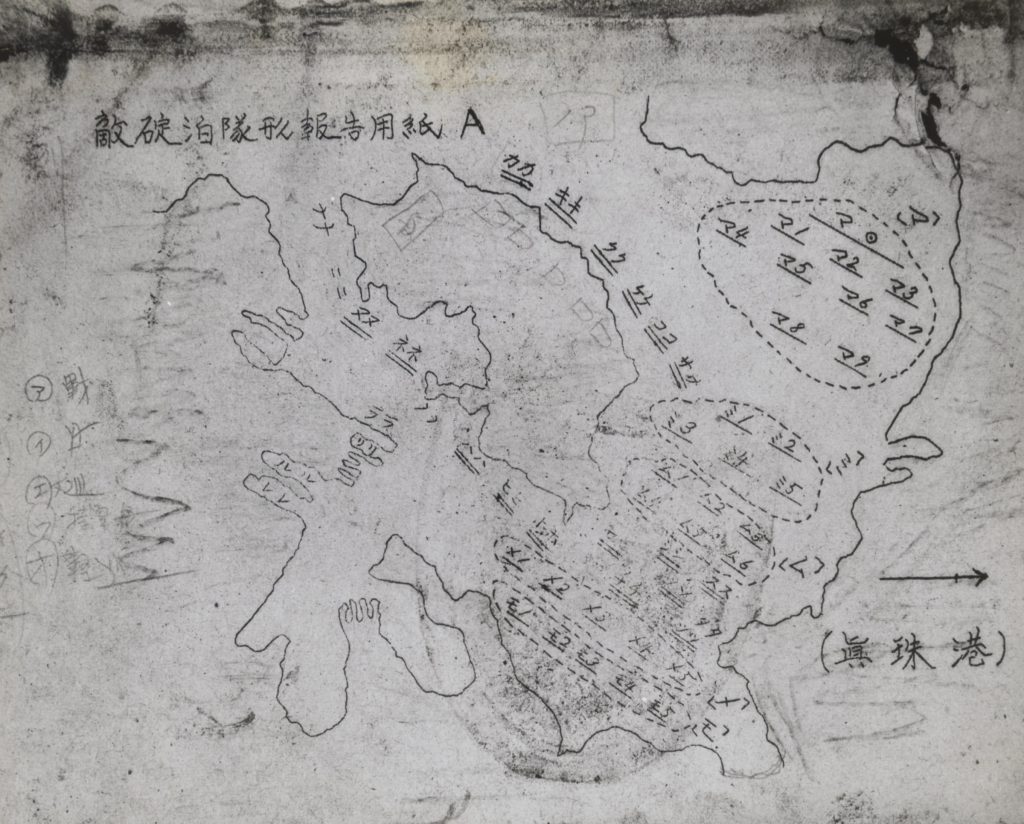

Two images show maps recovered from one of the planes. The kanji on one map reads “Enemy anchorage formation report form.” The characters on the other similarly say “Enemy anchorage formation report form B.”

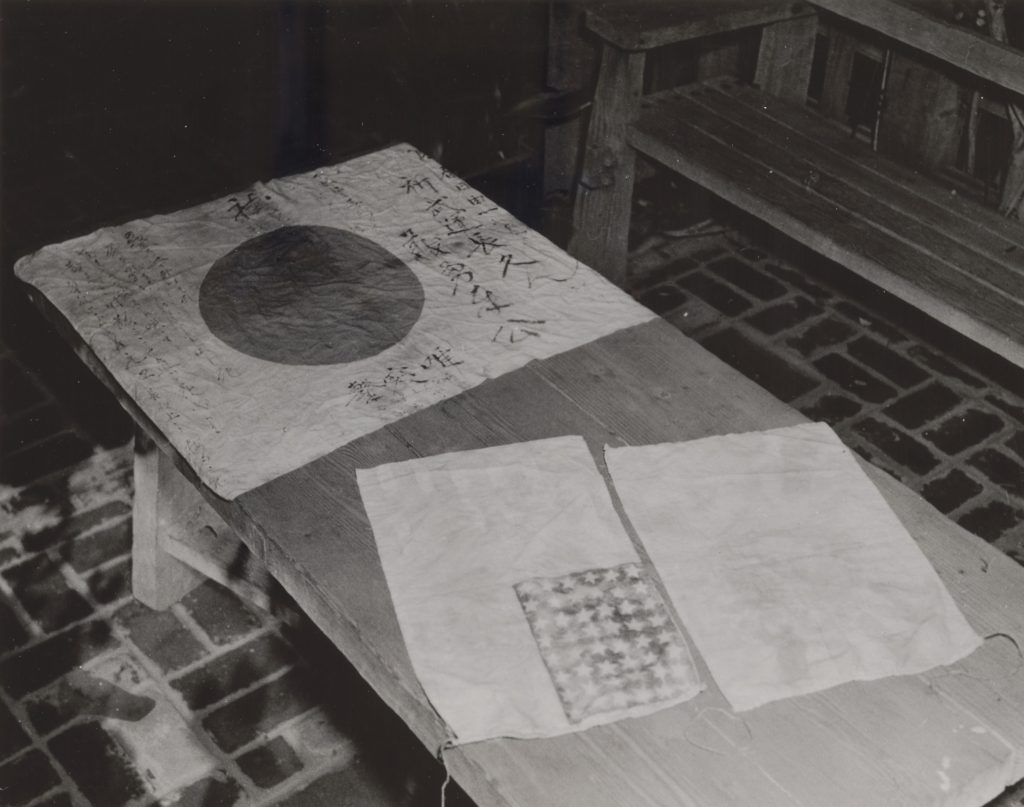

Another photograph shows flags taken from a Japanese submarine in a raid on Hawaiʻi.

Displayed on a table are a large flag of Japan and two smaller flags. One of the smaller flags is a very tattered American flag; the other is so faded it’s hard to see the print, but it appears to be the ensign of the Imperial Japanese Navy — a sun with rays.

Two pictures of Japanese prisoners-of-war reveal smiling. See them here and here.

The photos are part of the Admiral Furlong Collection at the Department of Accounting and General Services Hawaiʻi State Archives.

Adm. William Furlong was a U.S. Navy rear admiral during World War II and served as Chief of Naval Ordnance from 1937 to 1941. He was tasked with overseeing recovery operations at Pearl Harbor following the Japanese attack, salvaging and/or repairing the damaged ships.

Tensions between the United States and Japan were rapidly rising throughout 1941.

Imperial Japan began a campaign in the 1930s to expand its empire around the Pacific Rim, taking over China’s Manchurian region in 1931.

That was followed by 6 years of sporadic fighting between Japan and China until a full-fledged war broke out in July 1937 between the two nations after Japan invaded China and captured its capital of Nanjing.

Meanwhile, the Empire was expanding its military forces and began to align with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Germany and Japan signed a pact in November 1936, creating an alliance against the Soviet Union.

The Axis powers were then formalized in September 1940 when Germany, Italy and Japan signed the Tripartite Pact.

Expansion of Japan into China was widely condemned by the United States. Roosevelt grew increasingly concerned that the Empire would advance into Hong Kong, Southeast Asia and the Philippines, which was a U.S. territory at the time.

So in 1940, the U.S. government began to offer China assistance with aircraft and funding in the form of loans. The relationship between Japan and the United States deteriorated further throughout the next year, especially after Roosevelt’s government lobbied sanctions against the Empire and expanded its Lend-Lease program to give China military aid.

The United States was already by early 1941 supplying Great Britain in its fight against the Nazis.

U.S. policies and sanctions against the Empire continued to up the ante, becoming more aggressive as the year progressed. Japanese military leaders began calling for a surprise attack as the Empire grew determined to outright attack the United States.

Pearl Harbor’s destruction was conceived by Japanese Adm. Isoruoku Yamamoto, with its plans laid out by Capt. Minoru Genda.

The goal was to destroy the entire U.S. naval fleet in the Pacific, with their logic being that the United States would then be unable to interfere with Japan’s territorial conquests.

Yamamoto’s attack drew inspiration from the 1925 book “The Great Pacific War” by British naval authority Hector Bywater, in which a realistic account of a clash between the United States and Japan led to the destruction of the U.S. fleet and the Empire going on and attack Guam and the Philippines.

A victory won by Britain’s Royal Air Force against the Italian fleet in November 1940 while the Italians were at harbor in Taranto, Italy, convinced the Japanese admiral that Bywater’s fiction could happen IRL — in real life.

A large naval strike force — consisting of six aircraft carriers bearing more than 400 planes — set sail NOv. 26, 1941, from Japan, operating under strict radio silence and avoiding shipping lanes for its entire voyage so it was not detected.

The fleet journeyed about 3,500 miles across the Pacific to a location about 230 miles north of O‘ahu, where the Japanese would launch their attack on the unsuspecting Pearl Harbor and U.S. Pacific fleet.

A U.S. cryptologist the morning of Saturday, Dec. 6, 1941, gave her superior a message she intercepted from the Japanese about ship movements and berthing positions at Pearl Harbor. The ranking officer said he would get back to her about it Monday, Dec. 8.

A radar operator on O‘ahu the morning of Sunday, Dec. 7, prior to the Japanese attack, saw a large group of airplanes on his screen approaching the island. Upon calling in what he saw, the radar operator’s superior said it was likely a group of U.S. B-17 bombers scheduled to arrive that day and said not to worry about it.

Capt. Mitsuo Fuchida, who likely was piloting one of those planes seen on U.S. radar, after flying over O‘ahu and confirmed the United States military had no idea the attack was coming. Fuchida sent the code message “Tora, Tora, Tora” to the Japanese fleet, and the attack on Pearl Harbor began at 7:55 a.m. that morning.

Pearl Harbor marked the first time in nearly 130 years — since the War of 1812 — that the United States was attacked on its own soil by a foreign powers.

It also wasn’t the only U.S. territory to be attacked that day. The Empire also struck the Philippines, Guam, Midway Island and Wake Island, as well as British territories Malaya, Singapore and Hong Kong.

Japan had control of all those territories within a week.

The Empire was able to destroy or damage 19 U.S. Navy ships, including the 8 battleships. U.S. aircraft carriers were out to sea on maneuvers at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, leaving the U.S. Pacific carrier fleet intact.

The Empire’s strike force for Pearl Harbor consisted of a total 353 aircraft — including 40 torpedo planes, 103 level bombers, 131 dive-bombers and 79 fighters — launched from four heavy carriers.

The fleet also included two heavy cruisers, 35 submarines, two light cruisers, nine oilers, two battleships and 11 destroyers.

Japan lost just 29 aircraft and five midget submarines. One Empire soldier was taken prisoner and 129 were killed.

Yamamoto, as if predicting the future, feared that the United States would recover from the attack and eventually fight back after he learned Japanese forces did not destroy the U.S. carriers or completely wipe out the U.S. fleet.

As history goes on to show, U.S. forces recovered — and quicker than the admiral could have expected — and within 6 months after the Dec. 7, 1941, attack, the U.S. carrier fleet dealt a decisive blow to the Imperial Navy at the Battle of Midway.

That victory gave way to the island-hopping campaign U.S. forces used to push Japan back and the eventual defeat of the Empire in August 1945. Only one Japanese carrier survived the entire war.

Sunday (Dec. 7) is observed as National Pearl Harbor Remembrance Day each year in the United States, commemorated by special ceremonies at Pearl Harbor that invite U.S. survivors from the attack still alive today to attend.

None were able to make it to this year’s event. There are only 12 now still living, all of them centenarians.

It was the first year — outside 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic — no survivors would attend the remembrance ceremony at Pearl Harbor in recent history.

“The idea of not having a survivor there for the first time — I just, I don’t know,” Kimberlee Heinrichs told the Associated Press. “It hurt my heart in a way I can’t describe.”

Her 105-year-old father Ira “Ike” Schab — who has attended the remembrance ceremony six times since 2016 — had to cancel plans to fly in from Oregon after falling ill this year, .

The former tuba player on the USS Dobbin enjoys going not just to remember those killed but also in place of his late band mates, his three brothers who fought in World War II and the now-deceased Pearl Harbor survivors he has met.

Masamitsu Yoshioka was the last survivor of the Japanese force that attacked Hawai‘i 84 years ago.

Yoshioka was one of the select group chosen to launch the daring first strike against U.S. naval power in the Pacific. As navigator of a Nakajima “Kate” torpedo bomber, he helped sink the USS Utah.

He died in August 2024 at the age of 106 years old.

In a rare interview with American journalist Jason Morgan in 2023 and another with the Asahi Shimbun newspaper 2 years prior, Yoshioka said the 23-year-old him was excited to join a “great war” and honored to be chosen for such an important mission.

But he did not hate the United States and thought Japan should have continued down the diplomatic route instead of attacking Pearl Harbor.

Did he regret the infamous attack? He had not spoken about his experiences before those two interviews because, he said, “I’m ashamed that I’m the only one who survived and lived such a long life.”

The photos accompanying this story — from the camera lenses of Japanese military personnel involved in the Pearl Harbor attack — are only a few U.S. Admiral Furlong collected. View the entire collection on the Hawaiʻi State Archives website.

Big Island Now news reporter Nathan Christophel contributed to this story.

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)