Myth busted: Maunakea, Mauna Loa do not protect Big Island from tropical cyclones

It makes sense that many people believe Maunakea and Mauna Loa — Hawai‘i’s two tallest volcanic mountains, both at nearly 14,000 feet and side-by-side — can ward away Tropical Storm Calvin or any other tropical cyclone that is headed in the Big Island’s direction.

Nobody is alive to remember the last time a hurricane struck the Big Island — the Kohala Cyclone of 1871 — or the destruction it left in its wake.

That helps explain the origin of the myth that Maunakea and Mauna Loa protect the island from tropical cyclones, according to a research paper published in January 2018 in the Bulletin of the American Meterological Society.

“As a result of this long absence of hurricane impacts, a number of myths have arisen such as ‘the volcanoes protect us,’ ‘only Kaua‘i gets hit’ or ‘there is no Hawaiian word for hurricane,'” says the research paper: “Hurricane with a History: Hawaiian Newspapers Illuminate an 1871 Storm.” It was co-written by Steven Businger, a professor of meteorology at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa with a Ph.D. in atmospheric sciences.

The authors said if a similar storm of the same intensity were to happen today, the destruction would be far greater.

But maybe that hurricane was an aberration. Is it possible that the myth is right? That the two monoliths rising out of the middle of the Pacific Ocean do protect the island from tropical cyclones?

“No,” said John Bravender, the warning coordination meteorologist with the National Weather Service forecast office in Honolulu. “The terrain does not protect us.”

But while the mountains don’t stop the island from being struck by tropical cyclones, storms are affected by Hawai‘i’s terrain once they pass over land — just like their Atlantic counterparts.

“The terrain really disrupts the structure and low-level rotation of a tropical cyclone, causing it to rapidly weaken,” Bravender said.

That means Maunakea and Mauna Loa, along with the state’s other mountains, do play a role in protecting other parts of the state from tropical cyclones that come from the east. Tropical Storm Iselle, which hit the Big Island on Aug. 8, 2014, just east of Pāhala, is a good example of this. Not much of the storm was left after it passed over the Big Island.

On the flip side, the state’s topography amplifies and funnels tropical cyclone winds through channels between the islands and across ridges. It also can focus heavy rainfall on mountain slopes, causing destructive flash floods and landslides.

Think Hurricane Lane in August 2018 that caused one death and at least $20 million in damage, including from flooding caused by record rainfall in windward portions of the Big Island, even though it stayed well offshore.

Even a weak tropical cyclone can cause considerable property damage and losses because of the unique terrain of the island chain.

This is why meteorologists and other weather forecasters urge people not to become complacent in making storm preparations just because landfalls and direct strikes are somewhat rare in Hawai‘i. For information about how to be prepared, click here.

About 70 tropical cyclones (hurricanes and tropical storms) have affected Hawai‘i since the mid-20th century. Of those, only 10 made direct landfall, a small number compared to the hundreds of tropical cyclones during the same time period that impacted or made landfall in states along the U.S. Atlantic Coast and Gulf of Mexico.

The 10 cyclones that made landfall in the Hawaiian Islands since official record-keeping began in 1949 include three on the Big Island, two in recent history.

Iselle was the first tropical cyclone to make landfall in the state since early September 1992, when the most powerful hurricane in recorded history to strike Hawai‘i — Hurricane Iniki — devastated Kaua‘i.

Iselle walloped eastern and southeastern portions of the island, causing one death and at least $150 million in damages in Hawai‘i and Maui counties before moving west of the islands and being downgraded to a remnant low.

Tropical Storm Darby in 2016 made landfall July 23, also near Pāhala. The storm actually traversed the summit of Mauna Loa before re-emerging across waters near Captain Cook and trekking northwest, passing between O‘ahu and Kaua‘i as a tropical depression the next day, then dissipating July 25 west of Kaua‘i. Fortunately, while the storm produced torrential downpours in some areas, it didn’t cause much damage.

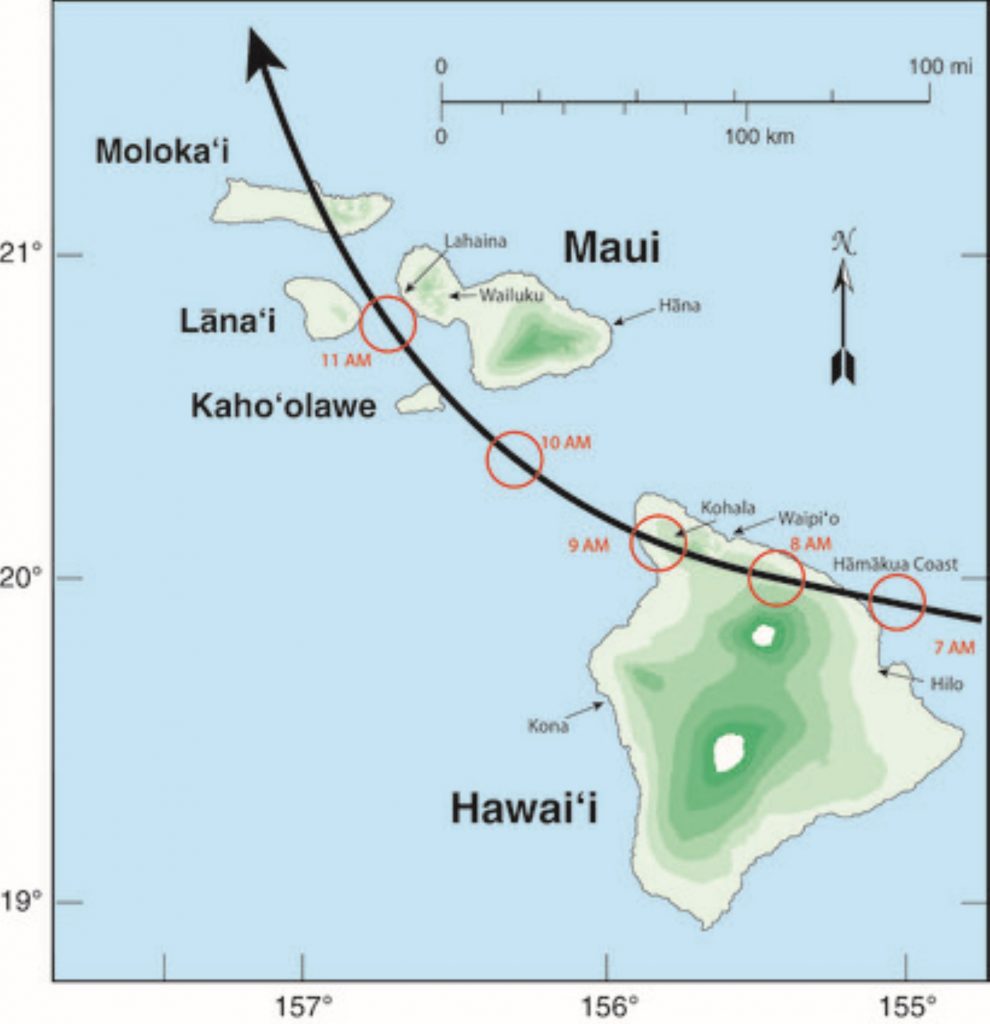

The Kohala Cyclone of 1871 was a Category 3 hurricane in today’s scale. It struck the Big Island and Maui on Aug. 9 of that year, causing extensive tornado-like destruction in its wake as it traveled up the Hamakua Coast and through Waipi‘o Valley and North Kohala before heading to the Hāna and Lahaina areas on Maui. It skirted the north side of Maunakea, with a portion remaining over water and the rest tracking over the lower Kohala range.

Hawaiian newspapers from the time provide accounts of that storm. It would be almost 90 years later before another recorded hurricane would make a direct hit on the islands. That was Hurricane Dot in early August 1959 that struck Kaua‘i.

The state’s location, however, is perhaps its best defense. Hawai‘i’s nearly 11,000 square miles is literally a drop in the Pacific bucket compared to the nearly 46,000 miles of shoreline from Maine to Texas that provide a large swath for storms to strike.

“We’re a small target in a big ocean,” Bravender said, adding Hurricane Douglas in 2020 passed only about 30 miles north of O’ahu. Its eye was visible on radar, but the state had no wind or rain associated with the storm.

“Most people don’t realize how narrowly we escaped damage because there’s no land north of us, just ocean,” he said.

Ocean water temperature also is a key. Tropical cyclones only thrive over areas of warm water. Currents from Alaska bring cooler water down the Eastern Pacific along the U.S. West Coast and then into the Central Pacific.

Storms generally form in the warm waters off the western coast of Mexico, south and east of Hawai‘i and then move west across the Pacific. Bravender said there’s usually an area of cooler water east of the state.

Because these storms need warm water of 80 to 83 degrees to maintain their strength and warmer than 83 degrees to get stronger, storms moving in from the east into that area of cooler water tend to weaken as they approach the islands.

Sea surface temperatures are typically warmer farther south, so tropical cyclones moving toward Hawai‘i from the south tend to have a better chance of surviving to the islands, which is what happened in the case of Hurricane Iniki, which formed south and east of the islands and stayed south, passing the state, before taking a turn to the north and then heading for Kaua‘i.

Drier, more stable air northeast of the state because of a high-pressure system typically parked there also deflects storms, keeping them farther south of the islands and steering them more directly west. There’s also wind shear, or a change in wind speed or direction, that destroys a tropical cyclone from above

Bravender said Hawai‘i has a lot of wind shear because of prevailing northeast trade winds at the surface and southwest winds aloft.

“Tropical cyclones can extend over 50,000 feet in the atmosphere and weaken if they get tilted, so they need little change in wind with height to develop and maintain their strength,” he said. “If winds at the top of the tropical cyclone are blowing from a different direction than the winds at the surface — i.e., if there is vertical wind shear or changing wind with height — then they will weaken.”

Hurricane season in the Central Pacific runs from June 1 through Nov. 30 each year. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted a 50% chance for above-normal tropical cyclone activity during the 2023 season.

“A key factor influencing our forecast is the predicted arrival of El Niño this summer, which typically contributes to an increase in tropical cyclone activity across the Pacific Ocean basin,” said Matthew Rosencrans, NOAA’s lead seasonal hurricane forecaster at the Climate Prediction Center, in May when the agency released the outlook for this year.

El Niño is a warming of sea surface temperatures in the Central and Eastern Pacific that allows warmer water to push farther north. That in turn means there is potential for more tropical cyclone formation closer to Hawai‘i and across the Eastern Pacific.

The phenomenon also can relax trade winds that can trap tropical cyclones well south of the islands, making it easier for them to be drawn north.

The geography, which includes Maunakea and Mauna Loa, and atmospheric conditions above and surrounding Hawai‘i create a crapshoot scenario for tropical cyclones of any kind looking to make landfall in the state. But as history shows, those conditions don’t make it impossible.

Because of that, officials urge people to be prepared, especially since impacts from a tropical cyclone aren’t just felt at their center or if and when they strike land. The effects of the storm can be felt far away from its center.

“We do worry about people taking preparedness seriously, whether it’s because of the protective myth or just because we’ve lucked out with several close calls recently,” Bravender said. “It’s too easy to become complacent and not prepare for events that have a low chance of occurrence, but it’s important to do so when the impacts can be as consequential as from a tropical cyclone.”

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)