Grammy winner and Lifetime Achievement honoree Kahumoku talks about his future

Just how multiple Grammy winner George Kahumoku has run a successful music career and a farm seems a bit of a mystery, until he describes his daily routine and great ʻohana. Oh, and somewhere in there he’s managed to earn three Master’s degrees — one in sculpture, another in business administration, and a third in fine arts.

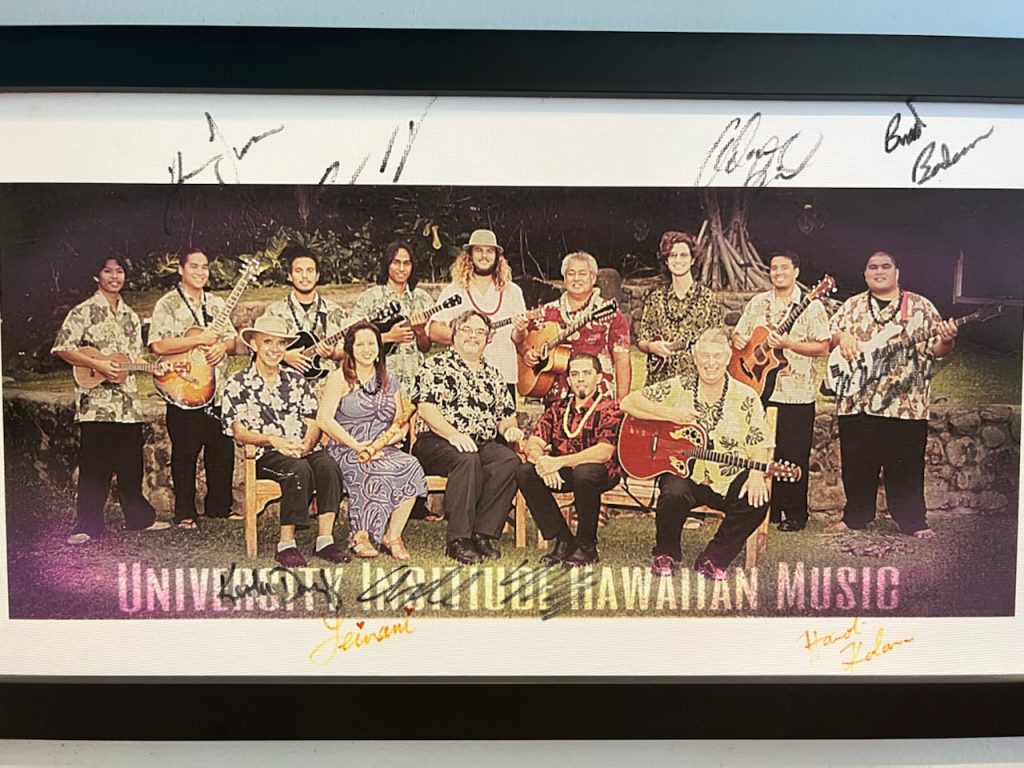

For more than 50 years, Kahumoku has not only contributed to a growing interest and respect for Hawaiian music, especially in the revival of kī hōʻalu, slack key guitar. He’s also helped in institutional building by founding the Institute of Hawaiian Music at the University of Hawaiʻi-Maui College. The Institute helps to train the next wave of songwriters in Hawaiʻi.

This year, Kahumoku is among a handful of musical artist to receive the Hawaiʻi Academy of Recording Artists’ 2022 Lifetime Achievement Award.

In this interview, Kahumoku describes a Hawaiian culture that nurtured his life as a musician, his artistic routine, and the “accident” that made winning Grammys possible. Maui Now writer Gary Kubota interviews him.

KUBOTA: Congratulations on being recognized by the Hawaiian Academy of Recording Arts for your “Lifetime of Achievement.” I have to tell you I’m fascinated by your many talents — singing and playing the guitar, writing songs and short stories, sketching illustrations — and farming? How did you learn how to farm?

KAHUMOKU: My Great-grandpa Willy Kahumoku and his eldest son, Uncle Pila Kahumoku, taught me on their farm in Kealia in South Kona in the 1950s. I grew watercress and taro at age three and raised my first animal, a horse named “Jimmy Boy,” at age five. Horses were a natural part of our lives. We would go Christmas caroling from house to house in our village on horseback. There were only two cars in the village. The cars served as taxis, and we used the taxis to go shopping 19 miles away in Kainaliu, or to the Kona Airport 50 miles away.

KUBOTA: Were the plants and your horse part of your daily responsibility?

KAHUMOKU: Yes, we were all given responsibilities as children. When I was three years old, my great-grandfather put four 1-foot sticks on the ground, forming a square foot, and told me that was my kuleana, my responsibility. The sticks were placed under our leaky red wood water tank. I planted the square with dryland water cress. By the time I was five years old, I had the whole sides of the 16-foot redwood water tank planted in unchoy and dryland water cress.

By the time I was 15, my responsibility expanded. I was taking care of a quarter acre of taro, bananas, wild yam, tapioca, sweet potato, coffee and breadfruit. When I was 30, I was farming almost 40 acres of mostly taro, Chinese ginger, bananas, awa, and cucumbers, and raising pigs and cattle. At 36, I was in charge of farming and ranching a thousand of acres in Kona, had 19 families working for me, and helped to run a slaughterhouse on the Big Island. I did all the above one square foot at a time — a method taught to me by great grandpa Willy Kahumoku when I was just three years old.

KUBOTA: That sounds more than a full-time job? Where did you find time to play and sing?

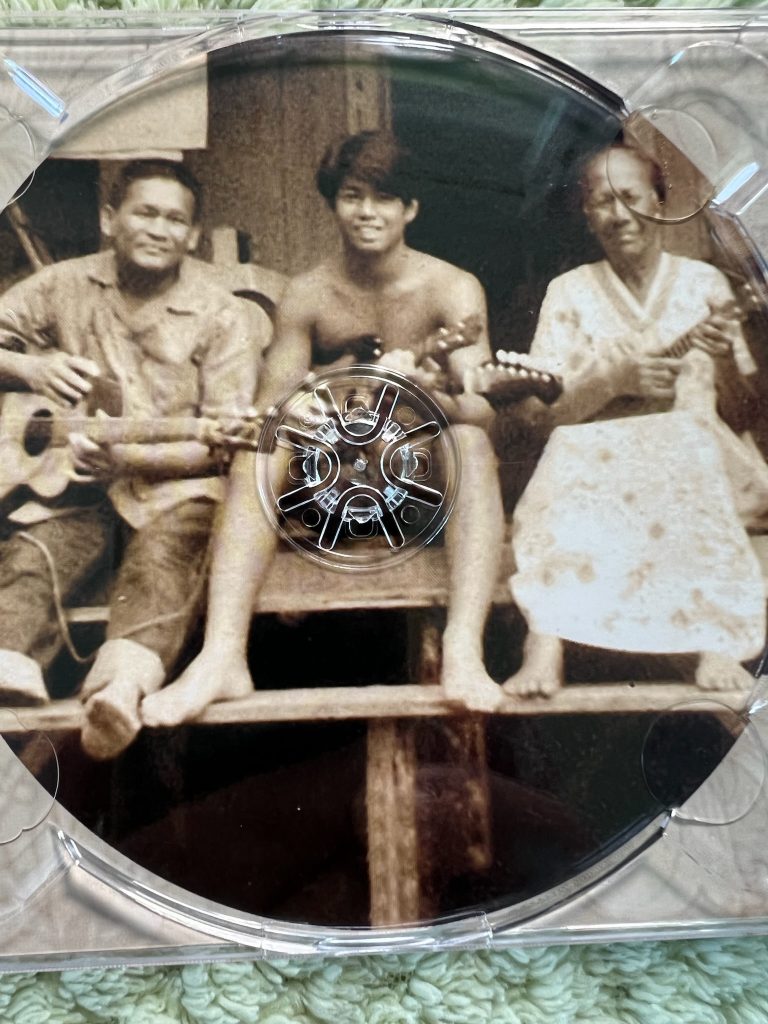

KAHUMOKU: I grew up in a musical family with 26 cousins. We all sang Hawaiian hymns at churches. Everyone played music. We played music six to seven days a week. Great-grandpa Willy was a Native Hawaiian practitioner and Kahu, a priest, for a Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He raised pigs, which was the mainstay for rights-of-passage events such as births, the first-year baby lūʻau, weddings, house warmings, canoe launchings and deaths. So, there was usually something happening — a party to prepare, the party itself, and the after-party event. Our ʻohana shared and played music at all these events. Later when Great-grandpa Willy died, his wife Tutu Ko’o Ko’o Ha’ae Kahumoku, who was a member of United Church of Christ in Kealia, Kona and a Kahu herself, met Filipino cowboy Grandpa Tommy Martinez who continued with the music events.

KUBOTA: How did you learn how to play the guitar in the slack-key Hawaiian style?

KAHUMOKU: Great-grandpa Willy was my main mentor and my dad, George Sr. An older cousin who grew up with Tutu Ko’ko’o and Great-grandpa Willy, Edward Michael Naihe, was my main inspiration. Out of the 26 cousins, cousin Michael was the best. My brother Moses was second best. I was maybe the 11th best player.

KUBOTA: I understand together you and your wife Nancy have three children and quite a number of hānai, adopted children?

KAHUMOKU: Nancy has a son and daughter from a previous marriage, and I got a birth son, Keoki, and 12 hānai children. So we have 15 kids, 34 grand kids and 11 great-grand kids all together.

KUBOTA: Perhaps much more than any Hawaiian musical artists, you’ve included dozens of artists in your compilation albums — albums that have won Grammys and helped their careers as well. Besides yourself, how many musical artists have been on your Grammy-winning albums?

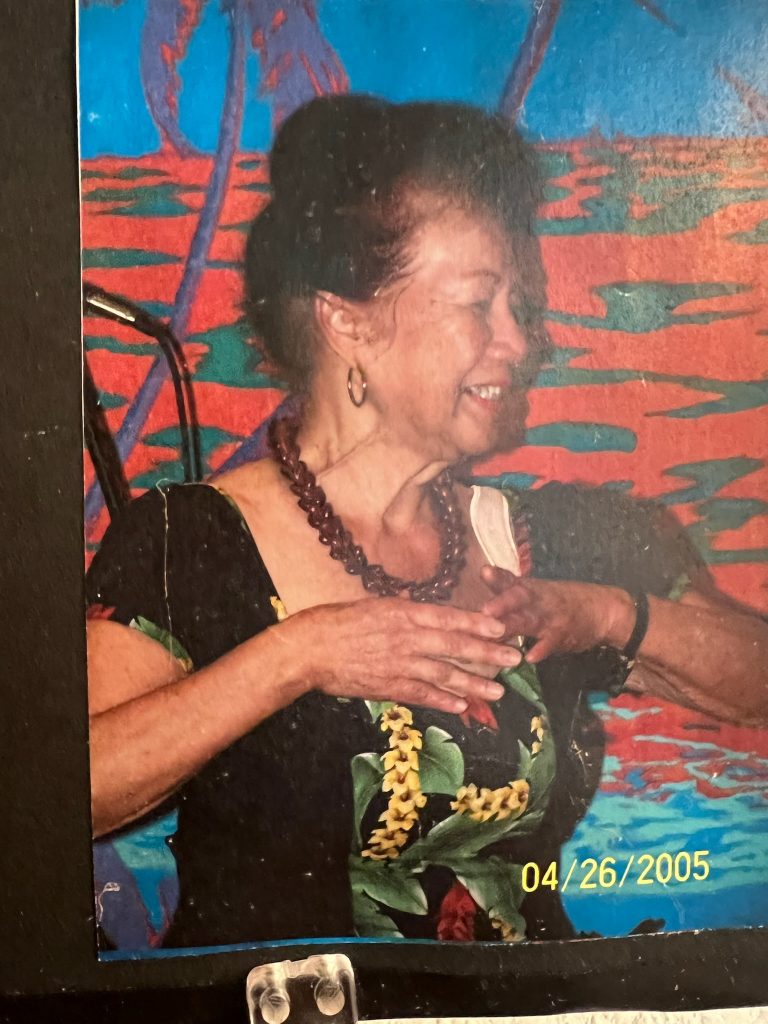

KAHUMOKU: We have recorded over 50 solo artists including Aunty Genoa Keawe, Ohta San, Richard Ho’opiʻi and Pekelo Cosma, Cyril Pahinui, and Dennis Kamakahi. More than 35 solo artists have been on our six Grammy nominee compilations and winning Grammy CD’s.

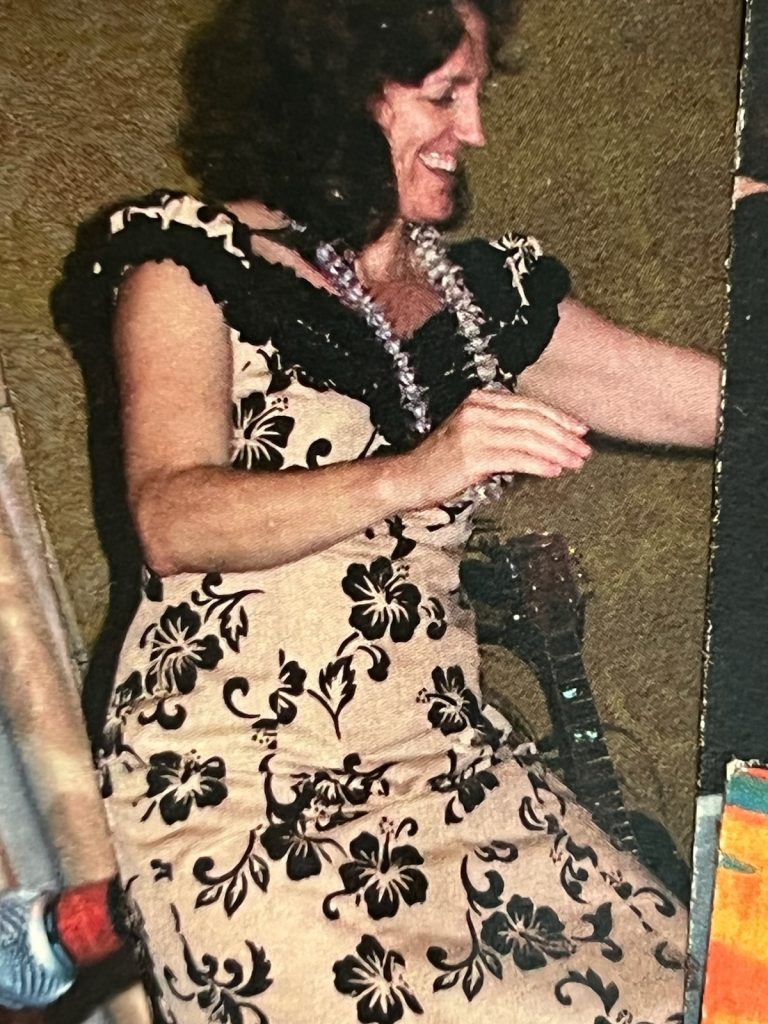

KUBOTA: I know your wife Nancy works closely with you, and she herself is the sister of well-known composer/entertainer George Winston. How has that helped you in your development as an artist?

KAHUMOKU: Nancy was her brother George Winston’s personal assistant for 15 years. GW trained her well. I stole her away from GW. Nancy fields all our family’s paper work and day-to-day work, so that I can stay focused on being creative and fulfill my passion of farming and feeding people. She also manages my weekly Wednesday Nāpili Kai Beach Resort “Slack Key Show” and does the marketing and social media. She fields music contracts, music licensing and royalty agreements and tries to catch the dollars we make to invest in our future, before I spend it all on the farm or feeding the homeless. I may be the creative center for all our endeavors, but Nancy is the heart, body, soul and hands and other body parts that keeps the Kahumoku heart running and beating. She does the day to day up keep and maintenance and keeps her hands on the beat of our music and branding. Nancy completes our relationship and love circle.

KUBOTA: What about George Winston himself?

KAHUMOKU: George Winston helped to open up the slack key music to the world by recording us and marketing us through Dancing Cat and Windham Hill, and distributing our music in 55 countries via BMG Production Music. I also had my own recording and publishing company – Kealia Farms Recording & Publishing Co. My first album with George Winston, “Drenched By Music,” sold well, thanks to him and his connections with BMG distribution. We got to play in performance centers for the arts, such as the Great American Hall in San Francisco and Carnegie Hall in New York City.

KUBOTA: There is some mention that the legendary Kui Lee, songwriter of “I’ll Remember You” and “Lahainaluna,” was a supporter when you were a youngster and attending Kamehameha Schools on Oʻahu. How did that happen?

KAHUMOKU: Kui Lee gave me my the first chance to make money. At 11 years old, my dad got me my first job in Honolulu. I was working at Lippy Espinda’s used-car lot as a car washer and gas attendant. Lippy paid us 10 cents a car to wash and wisk broom each car, and put on and wipe off a coat of Turtle Wax. My goal at age 11 was to do at least 10 cars on a Friday afternoon after school and make $1. Next door was Forbidden City, where Army, Navy, Marines and Air Force guys would hang out from 10 p.m. to 4 a.m. It was an adult entertainment spot. However, on Friday and Saturday afternoons from 3 to 8 p.m., it was where the carpenters, steel workers, dry wall, cement guys, and stevedores would hang out for $1 a pitcher of beer and free pūpū. The place was packed with 500 to 1,200 construction workers. Hawaiian entertainers Sam Kapu Jr. and Kui Lee were performing. Kui Lee heard me playing my guitar during a work break at the car wash and invited me into the Forbidden City building and stage to do a slack-key song. The stevedores and construction workers threw money on the stage. I made $27.10 for a three-minute song, making more dollars than I did working a month at the car wash. By the time I was 13, I was playing for the group “Eddie Akana & the Climax 5.” We took second place at the Waikīkī Shell with over 10,000 people there. That solidified my passion for music.

KUBOTA: What were the songs?

KAHUMOKU: At Forbidden City, I played Grandpa Willy’s slack key song that he taught me.

At the Waikīkī Shell, our group “Eddie Akana and the Climax 5” sang “Kalama’ula.” Eddie sang the song. We also performed “Mustang Sally.” I played it in slack-key guitar.

KUBOTA: How did your Grammy-award winning albums come about? As I recall, there were multiple Grammy wins in a span of five years in the Best Hawaiian Music Album category and they came from live recordings?

KAHUMOKU: The compilation albums were a reflection of our Slack Key Show on Maui which was the brain child of record producer Paul Konwiser and my childhood friend Wayne Wong. We originally recorded the shows for my wife Nancy’s brother, George Winston, to enjoy, so by accident, captured them. Winston was popularizing kī hōʻalu on the US mainland through his Dancing Cat Records label and tours. Daniel Ho, who performed slack key on the albums, had the vision, expertise, and Los Angeles connections to push the albums forward towards the Grammys.

KUBOTA: Lucky to have recorded the songs “by accident” and fortunate to have included Daniel Ho in the compilation of slack key. How did you start the concerts at the Ritz-Carlton Maui, Kapalua Resort?

KAHUMOKU: Konwiser preferred the Dancing Cat artists in the beginning. The show was a conceptual extension of Dancing Cat. Nancy knew the artists from working with her brother. The Slack Key Show was easy to book at the Ritz Carlton because of that connection and because of support from Ritz-Carlton cultural adviser Clifford Naeʻole. We later moved to the Nāpili Kai Beach Club Resort because of a renovation the Ritz on Maui.

KUBOTA: My understanding is that you were at one point a teacher at Lahainaluna High School in West Maui and worked with Lahainaluna students in a special motivation program? How did that come about?

KAHUMOKU: I moved from the Big Island to Maui in 1992 to play music at night at the Westin Maui in Kāʻanapali. The Westin Mauna Kea Beach Hotel on the Big Island, where I had played since 1974, had closed for two years of renovation. During the day, I taught special motivation and art at Lahainaluna from 1992 until I retired in 2010.

KUBOTA: Why special motivation?

KAHUMOKU: In teaching in indigenous cultures, I found that there is a disconnect between students and their families and our community and the educational system. What the alternative education and special motivation program did in my classroom was to create a sense of community for our special students to pursue their natural talents, not based on rote memorization and sitting for six hours straight everyday. They were talented in hands-on activities and needed to use that stored up energy. I had done this kind of work before as a school principal at Hale O Hoʻoponopono at the City of Refuge in Kona on the Big Island for Kamehameha Schools and Konawaena public schools from 1975 to 1992.

KUBOTA: What kind of hands-on activities?

KAHUMOKU: Mostly, I taught them how to feed themselves and their families and be sustainable. Most of my kids remember me for the work experiences and food we cooked and shared. In Kona as well as Lahaina, I taught kids how to plant and fish by the Hawaiian moon calendar and how to raise and slaughter pigs, sheep, goats, cows, feral animals like pigs and deer, as well as domestic chickens and pigs. At Lahainaluna, the students and I also harvested watercress, unchoy, Tahitian prawns, and cultivated wild clams in our irrigation ditch or awai. The students also learned how to frame doors and windows in a house.

KUBOTA: How did the founding of the Institute of Hawaiian Music at the University of Hawaiʻi-Maui College come about?

KAHUMOKU: The Institute was the brainchild of my friend Jonny Baldwin. I taught music, including guitar and ‘ukulele, at the University of Hawaiʻi-Maui College and used to jam and play music every once in a while with Jonny. He played a great banjo. We would play music jam and share music and songs on hand-written cheat sheets. Johnny told me that if I started a school for teaching Hawaiian music, he would support it. I raised over $450,000 from our Maui community and our patrons of the arts donors and Jonny Baldwin doubled it to $900,000.

Events began to come together. T.S. Restaurants’ Hula Grill started the yearly Hula Grill Contest on Maui with my son Keoki. Then TS Restaurants started doing ʻukulele contests on Oʻahu as well as Kauaʻi. The winners from these ʻuke contests and my workshops statewide became our students at UHMC – Institute of Hawaiian Music. They naturally fed into becoming the first students and graduates from the UHMC institute of Hawaiian Music. I became the founder and director of the Institute of Hawaiian Music in 2008. I retired in 2010, and Keola Donaghy took over, adding the ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi Language program — a much needed part of the Hawaiian curriculum.

KUBOTA: I know you’ve often used songs passed down by your family. What made you want to record songs of Queen Liliʻuokalani?

KAHUMOKU: I was asked to do the soundtrack for the film documentary, “ʻOnipaʻa.” My friend Meleanna Meyer produced and directed it. It’s an important film. The documentary was about the overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani in 1893 and the marches in the mid-1980s and early 1990s to ʻIolani palace. I knew most of the songs about Liliʻuokalani through my family. Some I learned from Kamehameha School, and some I learned from Pukaʻana Congregational Church in Kona and Ka Makua Mau Loa Church in Kalihi on Oʻahu. The film was first shown on PBS and then Hawaiʻi Theatre.

KUBOTA: What’s your favorite song by her?

KAHUMOKU: My favorite song is “Aloha ʻOe” because it touches everyone and makes a connection to people, and Hawaiʻi. This song connects me to my audience immediately no matter where I play in the world. It’s usually the first song I sing doing my set here on Maui as well as on the road. I also love the Queen’s Prayer, where she is asking God for forgiveness for the usurpers of her throne.

KUBOTA: What does that tell you about her to write a song of forgiveness?

KAHUMOKU: She let go and let God guide her.

KUBOTA: Have you done other soundtracks for films?

KAHUMOKU: Yes, several Hawaii-Five-0, Adam Sandler’s Bedtime Stories, The Descendants, Eddie Kamae’s “The Hawaiian Way,” Ray Kane’s film “That Slack Key Guitar,” and some German and French films about Hawaiʻi.

KUBOTA: When you are back at your farm, what are your daily tasks?

KAHUMOKU: Everyday I do my creative work first, try to write or draw before going outside. I try to write everyday for two to six hours a day. The farm chores are feeding the animals, picking ripe fruit, pulling and planting taro for the Maui Food Hub, Merriman’s, TS Restaurants and Tantes. We sometimes catch feral pigs and make smoke meat or kalua pig. We sell some, share some, mostly feed the homeless. Sometimes, we bow and arrow 15 to 50 deer that we donate to feed families in need on Maui. We have two part-time workers and many volunteers.

KUBOTA: What brings you the most joy and happiness in what you do?

KAHUMOKU: I get the most joy when I find a balance between my ʻohana and my creativity. My greatest joy comes from seeing my son Keoki and my other other students including Peter deAquino, Garret Probst, Sterling Seaton, Max Angel, JJ Jerome, and Marvin Tevaga succeed in music and take care of their families and become self-sustaining through the arts, hunting, fishing, and farming.

KUBOTA: What lies ahead?

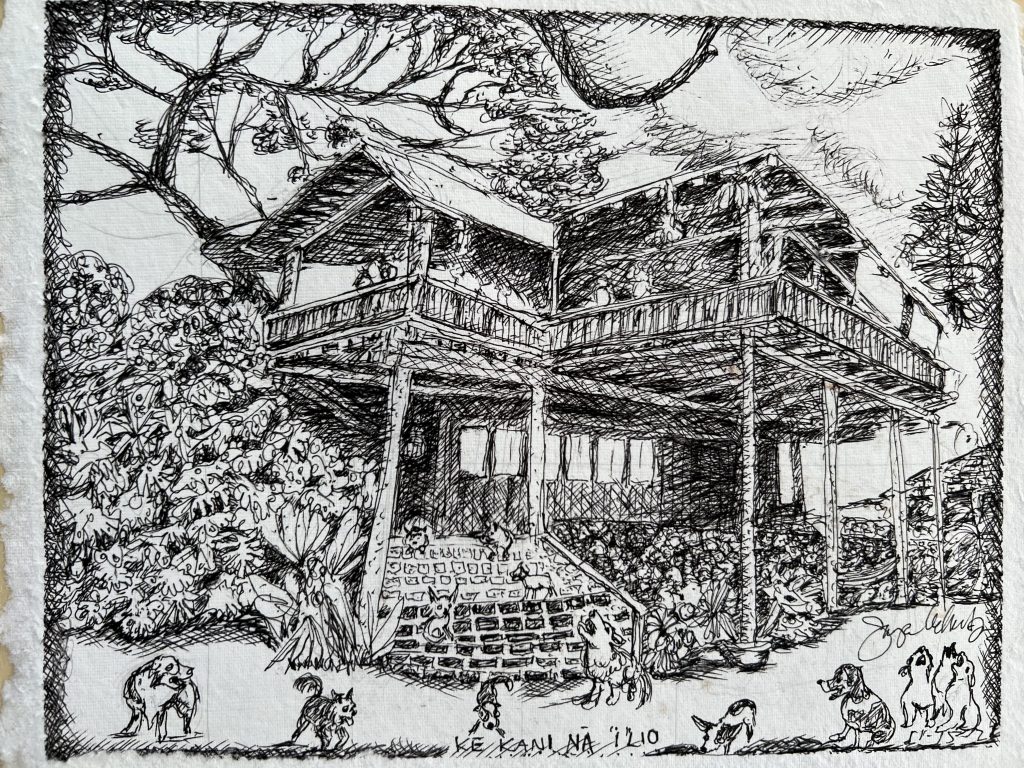

KAHUMOKU: I’m working on songbooks documenting my original songs, embellished with drawings and stories. I’m trying to leave a legacy of drawings, stories, and books about my life, music, native Hawaiian culture, especially in the area of planting and indigenous farming.

KUBOTA: You seem to have a huge body of work? How many songs, stories, and drawings?

KAHUMOKU: I have more than 1,500 chants and poems, over 300 songs, hundreds of stories, and thousands of drawings. I have published two books with about a dozen stories each. I have about 38 more books of stories but need to sit down and complete illustrations for the stories and books.

(To see a list of some of Kahumoku’s songbooks with illustrations and music as well as his Grammy-winning songs on CD, go to Kahumoku.com. He continues to perform regularly at his Wednesday shows the Nāpili Kai Beach Resort. A schedule of his resort show is at slackkeyshow.com)

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)