Survival of 4 Hawaiian Honeycreepers in Jeopardy, Extinction Study Shows

A new extinction study shows some species of the native Hawaiian honeycreepers could vanish in two years.

On Thursday, April 14, state and federal conservation managers shared a report that provides the most up-to-date scientific and biocultural information available to help inform emergency management decisions, aimed at saving four native honeycreepers: ‘akikiki, ‘akeke‘e, kiwikiu, and ʻākohekohe.

Avian malaria, a disease transmitted by invasive mosquitoes, is driving the potential extinction of Kiwikiu and ‘akikiki have fewer than 200 birds remaining and could go extinct in the next two years. A single bite from an infected mosquito can kill.

“Until avian malaria can be stopped from spreading, all native forest birds will be at risk of disappearing,” officials stated.

Dr. Robert Reed, Deputy Director, U.S. Geological Survey Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center (USGS-PIERC) states, “The report sought the expertise of biologists representing multiple organizations and biocultural experts from the Native Hawaiian community across the state. Their perspectives and knowledge are summarized in the report and will inform conservation managers working to prevent these four forest bird species from going extinct.”

The study was published by the University of Hawai’i at Hilo Hawai‘i Cooperative Studies Unit, which has worked closely with USGS-PIERC and its partners over many years to conduct field research and analyses that contributed to these demographic estimates. The consensus of the experts surveyed found that “in the long-term, the threat posed by invasive, non-native mosquitoes and avian malaria must be addressed.

Without intervention, the report paints a grim future for the birds. There are many fewer birds when compared to the last two decades and their available range has been significantly reduced as species move higher into the mountains to escape mosquitoes:

- ‘Akikiki

45 birds remaining on Kaua‘i

Range has been reduced by 68%

41 birds in captivity - ‘Akeke‘e

638 birds in the wild

Range has been reduced by 60%

7 birds in captivity - Kiwikiu

135 birds remaining on Maui

Range has been reduced by 41%

2 birds in captivity - ʻĀkohekohe

1,657 birds remaining on Maui

Range has been reduced by 61%

No birds in captivity

“The only long-term solution for many of the forest birds’ survival is landscape-scale control of the invasive mosquitoes,” stated Dr. Earl Campbell, Field Supervisor with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office. “We’re working with the State of Hawai‘i and partners in the Birds Not Mosquitoes Working Group to develop and implement a plan for controlling mosquitoes using a naturally occurring bacteria that prevents them from reproducing.”

That’s one of three management options evaluated in the report produced by the U.S. Geological Survey, FWS, and the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Office of Native Hawaiian Relations (ONHR).

“While most participants thought immediate steps are warranted to prevent species extinction, they also felt that the welfare of individual birds in their natural environment supported by Native Hawaiian cultural practitioners is equally important,” said Stanton Enomoto, ONHRʻs Senior Program Director. “It’s akin to ‘ohana supporting an ill family member undergoing treatment here in Hawaiʻi. ‘Ohana support for these bird species not only enhances their chance for recovery, but it sustains the biocultural relationship and preserves their legacy in the event they decline towards extinction.”

In addition to mosquito control, the other conservation actions identified in the report include:

- Bringing birds into captive care until such time landscape-scale mosquito control is achieved.

- Using conservation translocation to move birds from forests threatened by avian malaria or captivity to disease-free sites.

Currently, captive care facilities in Hawai‘i are close to full. The agencies are committed to placing birds in local facilities first and they are seeking the capacity, resources, and partnerships to increase captive care capacity here in Hawai‘i as an interim solution to the extinction crisis, meant only to prevent these species from vanishing from Earth.

The report does not recommend a specific course of action but evaluates which actions might prevent extinction and what decision-makers should consider when they implement any of the evaluated actions.

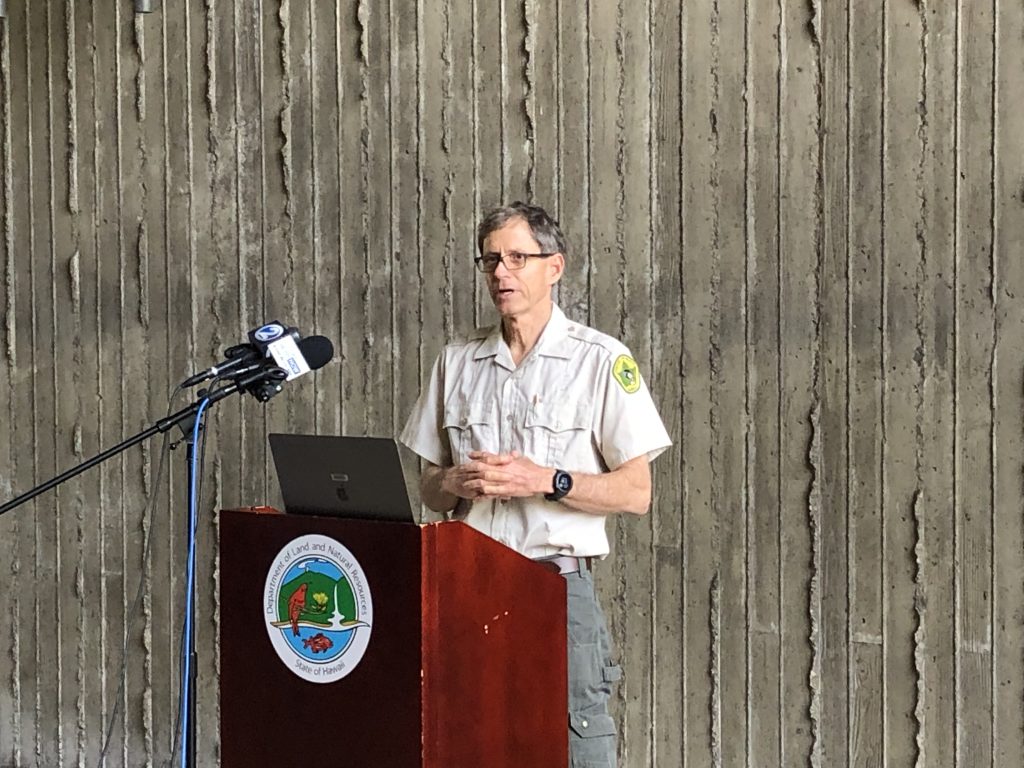

“The study provides dire predictions for these four bird species. The report is informing the urgent decisions we need to make as conservation agencies,” said David Smith, Administrator of the DLNR Division of Forestry and Wildlife. “We are working with FWS and a coalition of partners to determine which steps we can take to help prevent these birds from going extinct in the next one – ten years. We are committed to following the regulatory and public engagement processes required to take action on any decisions.”

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)