Study: Predatory Phytoplankton Key to Understanding Ocean Ecosystem

A team of researchers led by two University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa oceanography professors has revealed that an array of phytoplankton is not just using the light from the sun.

According to a press release from UH, the team, led by professors Grieg Steward and Kyle Edwards, has spent years taming mysterious marine microbes from the open ocean to grow in a lab in order to investigate their feeding habits. The group’s latest discoveries revealed that a wide variety of these phytoplankton in their collection are not just photosynthesizing; in many cases they are also voracious predators.

The study was recently published in The ISME Journal.

“We hope this work will give people a new perspective on these things we call ‘phytoplankton,’” said Qian Li, the lead author of the study and former post-doctoral researcher in the Center for Microbial Oceanography – Research and Education at the UH-Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, in the press release. Li is now a faculty member at Shanghai Jiao Tong University in China.

“A lot of beautiful complexity is hidden in that one word, and the more we look the more interesting things we find!”

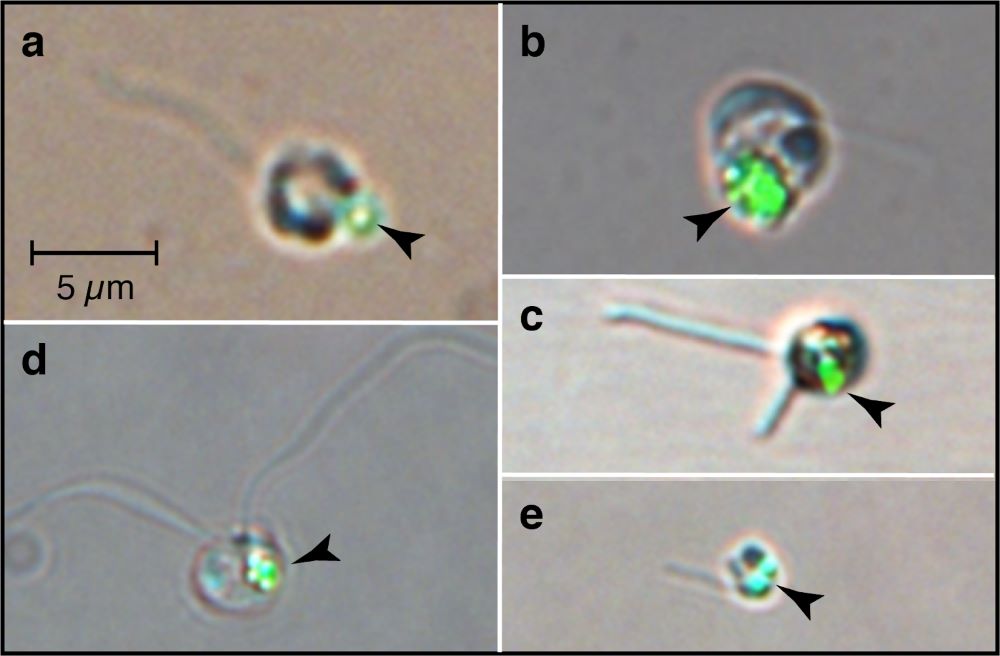

Phytoplankton use light from the sun to photosynthesize and grow, and some photosynthesize and eat prey, just like a Venus flytrap. But, unlike carnivorous land plants, these dual-function phytoplankton are microscopic — each is a single cell less than one-tenth the width of a human hair — and they swim using flagella to catch bacterial prey.

Because these phytoplankton mix two different feeding modes (photosynthesis and predation), they are referred to as mixotrophs.

“Oceanographers have known about mixotrophs for a long time, but interest in them has really been growing over the past decade as we learn just how prevalent and important they are in the ocean’s ecosystem,” Li said in the release.

One of the major contributions of the research, and foundation of the published study, was the cultivation of a large collection of diverse mixotrophs from the open ocean, a process carried out by Christopher Schvarcz while a graduate student and then post-doctoral researcher in the Center for Microbial Oceanography – Research and Education.

“Many of these species in our collection had been detected in seawater using trendy molecular identification methods, but they had never been grown in culture before,” said Schvarcz. “As a result, enormous amounts of data have been accumulating on who is living out there in the open ocean, but we didn’t know what they were doing or how fast they were doing it.”

“Having this unprecedented collection of species in culture is very exciting, and it completely changes the kinds of questions we can ask,” added Edwards, a study co-author.

One of those questions was how quickly do these mixotrophs eat Prochlorococcus — a photosynthetic bacterium and one of the single biggest contributors to photosynthesis in the open ocean. Figuring out what eats these tiny cells is fundamental to understanding the ocean ecosystem.

Mixotrophs appear to be major consumers of bacteria, and that would include photosynthetic bacteria, but until now there has been no direct observation that any mixotroph eats this key player of the marine food web, and no data on the rates at which they do so. That situation has dramatically changed with this new study that compared the feeding rates of dozens of unique phytoplankton isolates and quantified how feeding rates are affected by food availability.

“Dr. Li did an impressive amount of careful experimental work for this study,” said Steward, a study co-author, in the press release. “The number of new oceanic phytoplankton she characterized is extraordinary, and it revealed that different species of mixotrophs vary widely in their feeding rates. These data help fill a large gap in our knowledge about how different mixotrophs fit into the marine food web.”

The authors concluded from their work that mixotrophs are very diverse, abundant and widespread, and collectively they are eating a lot of primary production.

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)