Kamehameha Schools management plan for Keauhou Bay draws waves of community opposition

A deadly and devastating magnitude-9 earthquake on March 11, 2011, off the northeastern coast of Honshu, Japan, was the largest ever recorded in the Asian country and third-largest temblor on record since 1900 in the world. It triggered a significant nuclear power plant accident in Fukushima, Japan.

The quake also generated a destructive Pacific-wide tsunami that caused millions in damages in Hawai‘i, especially to the west side of the Big Island. Some places were slammed by waves 10 to 15 feet tall.

The Kailua-Kona area felt much of the terrible wave’s force, including Keauhou Bay.

While waters from the sea surge receded 13 years ago and the destruction was fixed or cleared, echoes from the tsunami are now causing waves of opposition as Kamehameha Schools moves forward with a management plan for land it owns along the shores of the small bay off the Kona Coast.

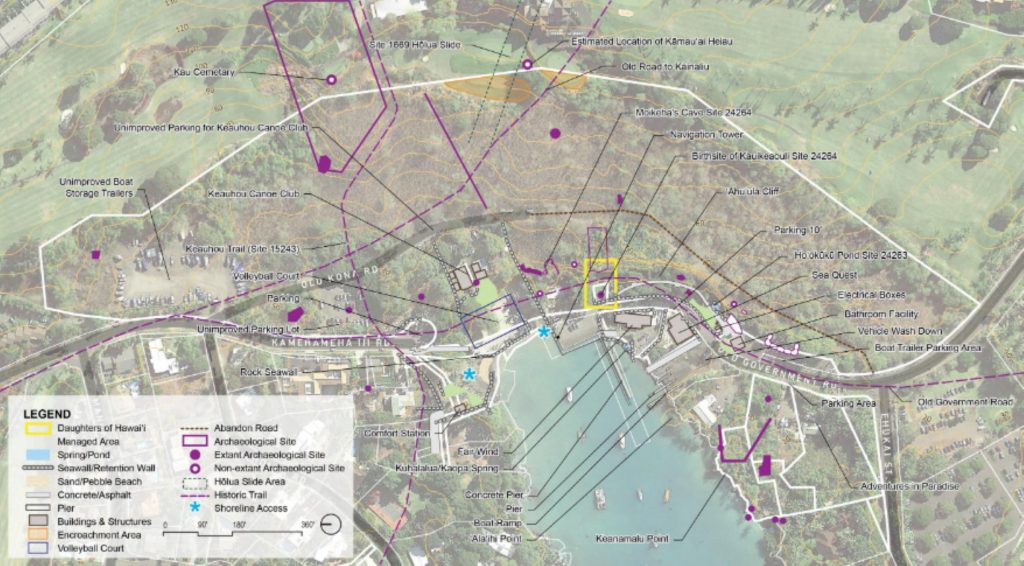

Kamehameha Schools is proposing the implementation of its Keauhou Bay Management Plan on 29.12 acres of its property at the bay. The trust owns a total of 54 acres at the site.

The majority of the land is largely undeveloped, and the project area is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean, the Kona Country Club on the east, a residential subdivision to the north and on the south by the Outrigger Kona Resort and Spa and Hōlua Resort at Mauna Loa Village.

The 2011 tsunami damaged some trust land at the bay, exposing a sewer line. When Kamehameha Schools went to Hawai‘i County for a permit to do emergency repairs, the trust was asked about its future plans for its lands at the bay because there were some nonconforming uses noted according to the area’s zoning.

Trust officials committed at the time to come back to the county with a comprehensive management plan for its land at Keauhou Bay after the emergency repairs were completed.

Those were the inklings of the management plan’s beginnings, but work truly got underway in 2016.

The environmental impact statement preparation notice for the management plan was published in March 2022 and a draft of the plan’s environmental impact statement was published in June.

Kamehameha Schools aims to enhance, revitalize and transform the bay area so place-based cultural education and revenue-generating opportunities are reoriented to better serve the Keauhou community, visitors, cultural practitioners, existing commercial activities and other landowners.

The public comment period runs through the end of today for the proposed management plan’s draft environmental impact statement, which determined the plans proposed projects will have no significant impact on the bay.

“We really wanted to shift the active use at the center of the bay to be focused on culture and education,” said Marissa Harman, Kamehameha Schools director of planning and development for Hawai‘i County who has worked with the private trust for the past nearly 18 years and is also a Kamehameha Schools graduate.

The trust devised a bubble concept, where each use of the bay has its own area.

To do that, existing commercial operators — Fair Wind Cruises and Sea Quest Hawai‘i — need to move to a new space, which Kamehameha Schools plans to build on the south side of the bay, near the entrance of Outrigger Kona Resort and Spa.

The space includes two retail buildings — designed after asking both commercial tenants what features they would need — and a pavilion for small gatherings or to simply get out of the sun, especially for those waiting to go on a tour with one of the two businesses, along with a 60-space parking lot.

Special treatments will also be incorporated into areas of the surrounding sidewalks, making sure people know which way to go for safety and directional purposes.

Fair Wind and Sea Quest are the only two tenants Kamehameha Schools has at Keauhou Bay. The trust hasn’t done any pre-leasing of space in the new commercial center, but it has told both its tenants it hopes they stay.

In fact, the two retail buildings and pavilion are the only three structures planned for the space right now. Other retail kiosks and even larger facilities could be built, but right now there’s no intention of building any.

However, when it is time to lease, Kamehameha Schools is open to talking to any business.

The new commercial area will also provide a different location for ocean recreation that now has no formal retail or check-in spots at the bay and will accommodate other support uses, such as truck deliveries, and maybe a bus drop-off area for educational programs.

The latter will help relieve congestion that often crops up near cultural sites and other locations at the bay such as the boat ramp, boat trailer parking lot, pier and harbor, which are owned and operated by the state.

But that traffic along with other state amenities such as 9 moorings, a double-lane, 30-foot-wide launch ramp and vessel washdown; various boating activities including commercial charter, private or commercial fishing operations; and other types of marine recreation such as but not limited to kayaking, snorkeling, stand-up paddle boarding, one-man and outrigger canoe paddling, swimming and fishing put added pressure on the bay itself and all of its cultural sites.

Other historically significant places along the base of the bay’s ‘Ahu‘ula Cliff include the remnants of Ho‘okūkū Pond near King Kamehameha III’s birth site, Ka‘ili‘ilinehe Beach at the bay’s head and Keauhou Canoe Club headquartered about 200 feet mauka (mountainside) of the proposed project area.

Vehicles enter the proposed project area from two single-lane paved roads — Kamehameha III Road and Kaleiopapa Street, both of which are Hawai‘i County roadways and extend from Ali‘i Highway.

“We don’t control a lot of the external forces that impact Keauhou Bay,” said Harman. “We don’t control the access, the roads. We don’t control the commercial permitted users and all of their visitors… But we feel the negative impacts of those uses. So we really felt compelled to what can we do with our land to help facilitate better use, better flow at Keauhou Bay, and also better honoring our cultural sites.”

The project will include a more than 40-foot setback from the bay’s shoreline and is planning for a 4-foot sea level rise by 2050. Kamehameha Schools also took into account the 100-year floods in the area.

One question those who oppose the proposed project asked is how the trust plans to protect nearshore waters and marine life in the bay from possible pollutants and sediments in runoff that are filtered out by earth and existing vegetation now before they reach the bay.

While additional parking is included in the trust’s management plan, which will also lessen the impacts of congestion, opponents are concerned removing the natural elements and replacing them with hard surfaces will only increase runoff and other woes for the bay.

Harman is confident Kamehameha Schools is up to the task of making sure runoff does not damage the bay’s environment or harm any of its plant or animal life — before, during and after construction.

“It was very thoughtful planning that goes into this water retention area,” she said. “We’re going to be required to capture any runoff generated on-site, and that’s standard for any development. … In fact, we feel like much of it may actually improve the current condition because vacant land is not managed. You know, the runoff just happens. Once we touch it and put infrastructure into place, we’re going to be managing that runoff on site and filtering it and slowing it down and all those things.”

Not only is the trust required to do it, it’s committed to best management practices to reduce and minimize all environmental impacts.

Harman wouldn’t expect anything less than the absolute best and added that oftentimes, trust officials and administrators behind these projects are Native Hawaiians, and they do more than is required.

Moving the two existing commercial tenants and repurposing the site on the south side of the bay, which would include other cosmetic and landscape improvements, is the first phase of a bigger vision.

Harman — who has worked on this project since it began in 2016 — said timing-wise, if everything is approved and moves forward without any hiccups, the first part of the proposed project could break ground no earlier than 2 years from now and ideally be finished by 2029.

There are permitting and other approvals needed before any construction can begin. Additional public input will be allowed along the approval process.

It looks like the final environmental impact statement — which would also include a comment period — wouldn’t be finished and approved until at the earliest the end of this year.

The second part — and the entire reason for the development as a whole — is the proposed ‘āina hānau (birth land) education and heritage center.

This will be a reimagining and renovation of existing facilities and surrounding grounds, including the stagnant Ho‘okūkū Pond which will be dredged and rejuvenated to as close to its original footprint as possible, on the south-central side of the bay’s shoreline near the state pier.

There would be major cosmetic changes to several acres surrounding the facilities to transform it into a cultural corridor at the bay, including special stone treatments like those across the sidewalks in the commercial center to help direct and keep pedestrians safe.

Existing landscaping will be pulled back and the land turned into a space available for ceremonial use such as hula. A new courtyard with some stone treatment will also be created.

Native Hawaiian landscaping will be added, some fencing will be removed and low rock walls will be installed in some places that can double as seating.

It’s all in honor of the historic landscape of Keauhou and the kūpuna and ali‘i of the area while having a space for keiki to enjoy Kamehameha Schools and community programming and others — including island visitors — to learn about Hawaiian culture and history.

The nonprofit Nakoa Foundation, which now operates a sailing program out of the bay, has already reached out to the trust to inquire if a marine activity or program could be started at the new education and heritage center.

The site also includes Mo‘ikeha Cave, and the Hōlua Kāneaka Slide, the largest and best-preserved slide in the state.

The trust plans to keep a large buffer around the slide to allow for its future restoration, perhaps with a community collaborator.

Jeff Caufield is an environmental attorney with more than 30 years of experience who has been a part-time resident of Keauhou Bay for nearly just as long. He has been a frequent user of the bay for the past 20 years and spent more than 200 hours observing the bay’s use for the past 2 years.

He’s also an avid beach volleyball player and has played hundreds, if not thousands, of games on the Keauhou Bay court, and he and his wife raced with the Keauhou Canoe Club a number of years ago.

Now, they’re just old people who sometimes paddle out with the “gray hairs” in the mornings during the week when everybody else is working. They take it slow, but it’s still exercise.

“Keauhou Bay is a magical place,” said Caufield, “and it is unique, even on the Big Island.”

Not only is it the home of the kings, the bay offers a calm environment — there are no waves, it’s easy to launch boats, and it offers abundant food sources in and out of its waters.

It also still has freshwater springs, which is extremely unique in the islands.

Caufield said it’s understandable why the royal family chose Keauhou Bay as a place to live and of such importance.

The bay also offers a quiet, peaceful and serene piece of accessible coastline — a sparse amenity in the 8.3-mile hotel-, resort-, development- and tourist-laden stretch heading north along the Kona Coast until you get to Old Kona Airport State Recreation Park on the outskirts of Kailua-Kona.

Caufield said the Kamehameha Schools proposed project, especially with the low-impact housing portion included, creates the prospect that Keauhou Bay will just become another Kahalu’u Bay or Magic Sands Beach — another tourist trap, a big development that caters to the service industry and high-end travelers.

“That’s disturbing and it’s unfortunate,” he said. “It’s not just a resort. It’s a resort, it’s parking lots, it’s paid parking lots, it’s commercial kiosks, it’s a restaurant, it’s commercial retail, it’s a cultural center. I mean, they’ve got a lot of things they’re doing at one time.”

A proposed third phase would include reclaiming an overgrown road and the construction of 43 buildings that would house 150 low-impact lodging units on a bluff above the bay on Kamehameha Schools property zoned for resort.

Harman said the trust could have designed the project with 745 units but decided to keep the number low: “We’re not trying to maximize,” she said.

Planning and construction for that phase, however, wouldn’t start for at least another 5 years.

“I just want to reiterate, this is about a comprehensive plan. This is about the county asking us, what is your whole long-term plan,” Harman said. “So this is not happening tomorrow. The improvements to the commercial, the change in the cultural education, those will all be pieces that get in place first with this approval. But most importantly, it is a package. We were asked to look at it comprehensively so they know anything and everything we want to do on these lands for the long term.”

The third phase isn’t even set in stone. Harman said it’s it’s to be determined and would be based on updated financials and outlooks.

The trust included it in the draft environmental impact statement because it wanted to get it permitted now. The actual timeline, if it does move forward, could be pushed back depending on how the books look.

It would also largely hinge on rebuilding Old Kona Road, a former street that is overgrown and no longer in service owned by Kamehameha Schools. The roadway would be an important key to congestion relief if the lodging is constructed, which is another main concern of project opponents.

Much of the opposition is based on the “resort” part of the proposal, which refers to the low-impact lodging.

In fact, a website set up by Rebecca Melendez, a dive master with a 100-ton captain’s license who moved to Kailua-Kona in 1992 and is a frequent user of Keauhou Bay, specifically says it is “NOT against the educational center they want to build in the already developed land.”

“This page is against the bungalow resort development they want to build by clearing the ONLY land that helps protect Keauhou Bay from golf course pollution,” says the website.

A petition Melendez started in April 2022 against the Kamehameha Schools development plan had 6,299 signatures as of about 9 p.m. Tuesday, the night before the public comment period ended for the draft environmental impact statement.

The concern is that additional runoff will contain pollutants and sediment that will harm the environment of the bay and further threaten endangered or threatened species such as Hawaiian monk seals and green sea turtles and the coral that make the bay their home. Even the manta rays and spotted eagle rays that commercial entities rely on to make a living.

They also worry additional foot and vehicle traffic — which Caufield estimated might be upward of about 100,000 extra people a year based on visitor numbers at the nearby City of Refuge — would damage the air, noise and water quality of the bay area.

The additional traffic could also cause safety issues for the extra people visiting the bay, especially those who might have to walk from one part to another for snorkeling, manta ray dives and other ocean activities after the commercial center is moved to its new location.

Harman said the plan calls for those special inlay treatments to help direct pedestrians and also looking at raised walkways to help with those safety concerns.

The trust is going to work with the state as well to tweak traffic flow in and out of state-owned facilities, including the boat ramp, pier and boat loading area, and offer additional boat trailer parking space so congestion becomes less of an issue.

Reopening Old Kona Road and having some extra available parking will further alleviate more of the expected pressure of the space as well.

Opponents, including Caufield, say Kamehameha Schools hasn’t done enough homework on the existing conditions of the bay and more research is needed before development plans can move forward and they forever change the area’s ecosystem and atmosphere.

“This development will change this entire ecosystem,” said Melendez, “and it doesn’t have to be changed.”

She and other opponents say the trust has other land that is undeveloped and not being used. They also say trust lands that have been developed could be used more.

Melendez is skeptical about how long the Keauhou Bay project will take to develop since it’s taken Kamehameha Schools more than a decade to finish a project on land at Kahalu‘u, which she said is yet another property the trust could use to generate revenue if it needs it.

“We don’t want this,” she said. “We don’t. We come here for this beautiful peace, this beautiful atmosphere, this tranquility, the marine life. That’s why the tourists come to this area, because that’s what’s here, and if they change it and make it into another Waikōloa Hilton. … That’s north. They can stay there.”

Melendez is specifically disappointed in Kamehameha Schools for doing what she sees as wanting to cater to tourists and other opponents see as a money grab instead of doing what it’s supposed to according to what they say Princess Ke Ali‘i Bernice Pauahi Pākī Bishop entrusted it to do — provide first and chiefly a good education for the Hawaiian people.

“Not to develop a bungalow resort for high-end tourists and educate the high-end tourists on Hawai‘i state land that was endowed to them for the Hawaiian people for their education and educate these high-end tourists on the culture of Hawai‘i,” she said.

When Bishop was born, about 124,000 Native Hawaiians were living. By the time she wrote her will, which is what created the trust for Kamehameha Schools, there were only 44,000 left. She thought education was the key to her people’s success.

So she established the trust, which came with a large land endowment. That consists of property inherited by her from her family lineage, most of which, more than 80%, is on the Big Island and is land conquered by Kamehameha I.

Kamehameha Schools has just more than 300,000 acres on the Big Island alone.

The trust has a $14.6 billion endowment, yes, but it does not have access to that in cash. Much of it is tied up in real estate holdings and other financial investments.

It also purposefully has a conservative spending policy so it can be here for Native Hawaiians in perpetuity like the princess wanted.

It spends between 4% and 6% of a rolling average of the value of the endowment each year, so for the year ending June 23, Kamehameha Schools budget was $486 million, of which the majority, $272 million went directly to its education programs at its 3 K-12 campuses statewide that serve about 7,000 students.

Only about 1% of trust lands are dedicated to preschools and other trust campuses.

The trust spends another $96 million reaching another 70,000 students through its post-high school scholarships and stipends to other community educators for students who can’t attend classes on Kamehameha Schools campuses or want to go to school in their own community.

About two-thirds of the total 371,000 acres of land the trust owns statewide are stewarded for conservation, with many supporting watershed efforts and conservation programs.

Another 29% of its lands are used for active agriculture, with 900 farmers and ranchers leasing land from Kamehameha Schools statewide. About 75% of Kona coffee is grown on trust lands.

In fact, Kamehameha Schools is the largest private landowner in the state that is actively involved in agriculture.

Then there’s about 4% of trust land that is actually in a commercial real estate portfolio, which includes hotels, retail centers, shopping centers, industrial and some residential.

“So we just want to be clear for folks,” Harman said. “We are much more than a school. We are much more than just Keauhou Bay. But most times people only know us for that sliver of [Kamehameha Schools] that is in their backyard or their community.”

Keauhou Bay is an area that is high in demand. Harman said it’s almost a big event every day whenever a commercial operator is going out.

So the trust was compelled to do what it could with its land to help facilitate better use and better flow at the bay — also better honoring the existing cultural sites there.

Kamehameha Schools isn’t shy about saying its assets are underperforming financially either.

“I think as part of our fiduciary responsibility to ensure that we are here in perpetuity is to also be conservative in how we are spending our mission funds towards stewarding our assets that enable us to then keep paying for our mission, which is educating students,” Harman said.

Concerns from the community also include the project replacing an existing unsanctioned sand volleyball court on the bayfront that is now heavily used by the Keauhou community with a proposed green space and what ramifications the development might have on the Keauhou Canoe Club facilities by reorienting them.

Caufield said removing the volleyball court will cause congestion at other sand volleyball courts in the area as well.

Kamehameha Schools has been meeting during the past couple of years with leadership of a group that represents volleyball players who use the court. There is no land use agreement for anyone to use the court.

Harman said the group was told that for now, they can stay, but there is no plan to keep the court because it constitutes an exclusive use of the shoreline and people have said they don’t necessarily feel welcome there.

Plus, the volleyball court and canoe club in the same vicinity don’t leave much space for other people to be there.

Concerns about loss of public access at the bay also have been expressed by opponents. Harman said there already are many public access areas at the bay and that will not likely change.

“Most folks know regulators would not allow these things to slip under their radar,” she said. “There’s no way that a regulator would approve a project in this day and age that cuts off public access. In fact, they demand more of it.”

And despite what some opponents claim that the draft environmental impact statement doesn’t include alternative projects, the 434-page document does contain 4 alternatives to the proposed project. You can find them starting on pages 1-19.

During the early stages of planning for the management plan, the trust hosted a public scoping meeting for the environmental impact statement preparation notice.

Throughout the past 8 years, it’s hosted more than 100 meetings with community members and stakeholders including kūpuna, lineal descendants from the bay area, the Daughters of Hawai‘i who the trust works with to care for the cultural sites at the bay, the Keauhou Canoe Club, commercial operators including those who are not tenants at the bay and others.

Those meetings ranged from audiences of 2 to 20 people.

Kamehameha Schools also hosted one large meeting about the proposed management plan at the Sheraton for all the people who live on north side of the bay — the immediate stakeholders in the area including every homeowner and condo association member from that area.

There have even been site visits with individuals, including Melendez.

The trust is now in the early stages of planning a kind of community open house to discuss the project and management plan. More details are to come.

“It’s not required, but we felt like it would be helpful to get people more information,” Harman said.

She called the Keauhou Bay development plan a “catalyst project,” and Kamehameha Schools is committed to reaching its goals for the bay.

The trust’s leadership wants the plan to jump-start discourse of spatial legitimacy, which noted Native Hawaiian scholar Konia Freitas from the Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies explained is a need to respond and challenge certain assumptions that Native Hawaiian values can’t be authenticated in contemporary urban form.

“Freitas postulates that planning for places that are inclusive of Native Hawaiian perspectives, in response to these questionable assumptions, must begin through an inclusive framework that goes beyond an aesthetic response but seeks to be ‘generative of social, economic and political meaning,'” says the management plan’s draft environmental impact statement.

Opponents have concerns about whether the bay’s infrastructure can handle an increase in services necessary for the proposed development, but Harman said the county is supportive of the project and grateful for the services and upgrades it would bring.

But for some, parts of the project simply go too far and it seems they will continue to ride the waves of opposition.

“We’re trying to be loud right now to say if we can stop this now, change Kamehameha Schools’ mind and let Kamehameha Schools know there are other alternatives they can do, they have property that’s already developed, there is a lot of the community that does not what this and if we can be loud now, then hopefully we can stop it now and change Kamehameha Schools’ mind,” Melendez said.

For more information about the Keauhou Bay Management Plan and read or leave a comment on the draft environmental impact statement, click here.

To read more about the opposition or to sign the petition against the plan and proposed projects, click here.

Sponsored Content

Comments