New bacteria species identified off coast of Hawaiian Islands

A new species of bacteria has been discovered off the coast of Oʻahu.

Researchers at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa believe this discovery will shed light on how unseen microbial life connects Hawaiʻi’s land and sea ecosystems.

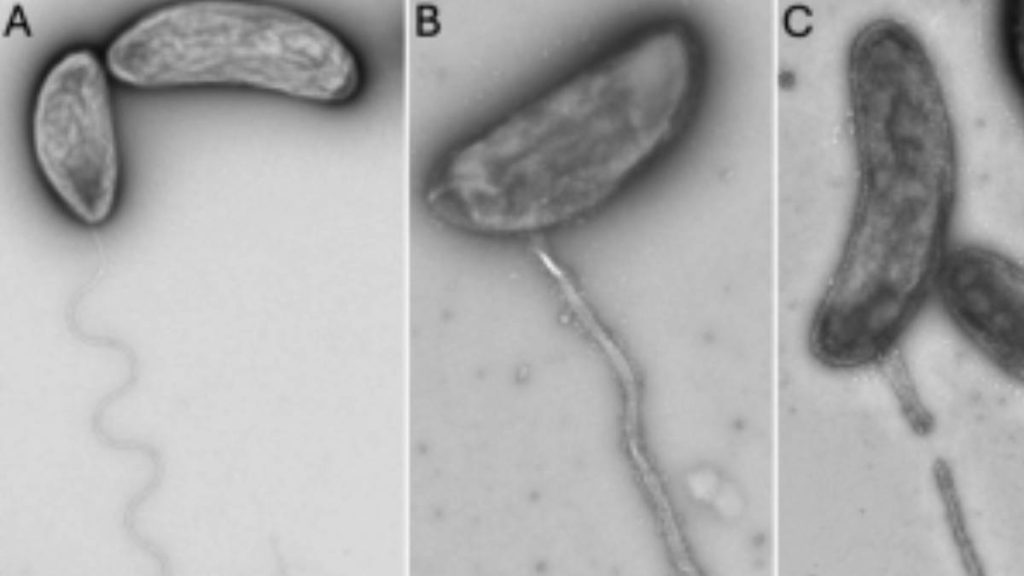

The bacteria, identified Caulobacter inopinatus, was a previously unknown species of bacteria found in seawater collected near a beach on Oʻahu’s south shore, according to a news release from University of Hawai‘i. It was discovered when an undergraduate marine microbiology class began a routine demonstration on how to grow bacteria from seawater samples.

When one colony growing on a Petri dish looked different from all the other colonies, further testing confirmed it was something entirely new.

The finding was published on Oct. 16 in the International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology — was unexpected because all other known species in the Caulobacter genus (a scientific group that includes closely related species) are from freshwater or soil environments, not the ocean.

The species name, inopinatus, comes from the Latin word for “unexpected,” reflecting both the chance nature of its discovery and its surprising characteristics.

“Understanding how microbes move between land and sea helps scientists track the flow of nutrients and contaminants that can affect coastal water quality, fisheries and coral reef health—issues that directly impact Hawaiʻi’s communities and economy,” said study co-author and University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa School of Life Sciences Professor Stuart Donachie. “Discoveries like C. inopinatus help us better trace how land-based activities and natural processes influence marine environments at a microscopic level.”

According to the research, scientists found that C. inopinatus cannot survive in salt concentrations typical of seawater, despite being isolated from it.

“This paradox led researchers to investigate how it ended up in the ocean,” the release stated. “They determined it was likely transported from land by submarine groundwater discharge — the natural movement of fresh groundwater through the seabed into the sea.”

These discharges are known to carry nutrients and pollutants into nearshore waters; in this case, they may also move land-based microorganisms. Microbial exchanges are important because bacteria play critical roles in nutrient cycling, water quality and coastal ecosystem health.

The research was part of ongoing microbial diversity studies led by Donachie. Undergraduate researchers Austin Dubord and Mia Sadones contributed to the project through UH Mānoa’s Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program, which supports student-led research and creative work. Collaborators included UH Mānoa faculty Michael Norris and Jennifer Saito, graduate students Chiyoko Onouye and Thi Hai Au La, and University of Mississippi Assistant Professor and UH Mānoa PhD graduate Rebecca Prescott.

The study is dedicated to the late UH Mānoa Earth Sciences Professor Craig Glenn (1954–2024), whose pioneering research on submarine groundwater discharge in Hawaiʻi helped illuminate how freshwater and seawater interact along island coastlines, and to former UH undergraduate student Justin Bukunt (1983–2011), whose early research on groundwater discharge at Kawaikui Beach Park informed this discovery.

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)