‘Evil twin’ or not, newly discovered exoplanet will help get closer to answers about why life appeared on Earth

Planets are not born inherently “evil.” It’s all about nature and nurture.

The environment they’re raised in constantly changes them as they grow, which can cause even the best behaved little cosmic chunk — with all the potential in the universe — to become a ruinous rock lethal to life.

Venus and Mars are examples in our solar system of how Mother Nature initially nurtured them to have similar conditions to Earth — those required for life to appear.

They were three peas in a pod until she shifted all of her planet-rearing attention to the golden child we now call home while the other two eventually became Earth’s lifeless “evil twins.”

It might turn out that a newly discovered exoplanet is one of those dastardly doppelgangers, but researchers hope it could someday lead to answers for why life appeared on Earth.

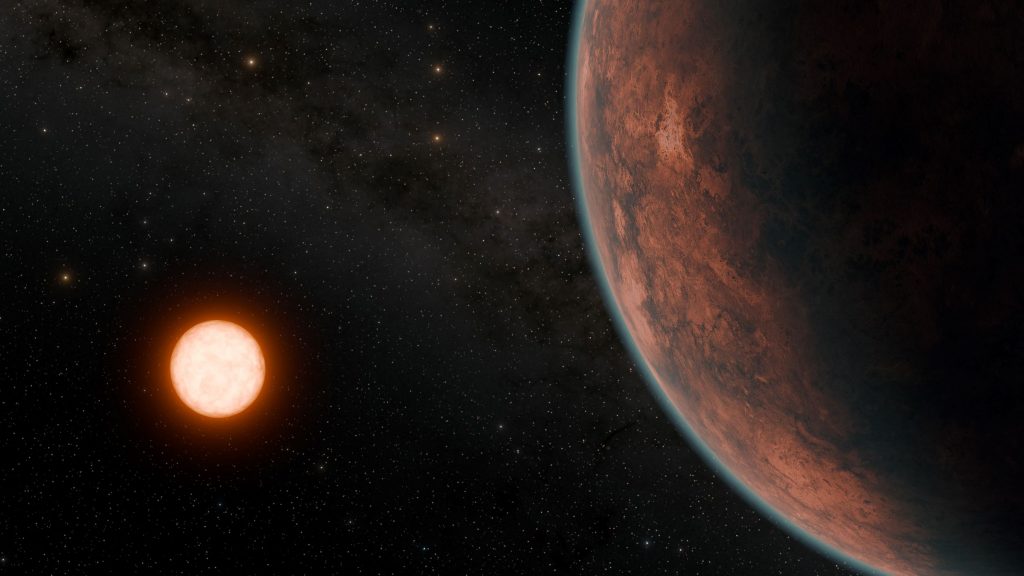

An international team of scientists, with the help of three observatories atop Mauna Kea on the Big Island, discovered the relatively close exoplanet dubbed Gliese 12 b in our galactic neighborhood.

Located 40 light-years away, or 235.1 trillion miles, it would take humans — in the fastest chemical rockets we’ve ever made — between 600,000 and 700,000 calendar years to get there. But even at that distance, Gliese 12 b is closer than a majority of the more than 5,500 exoplanets found and cataloged since the 1990s.

Most are hundreds of light-years away.

Similar in size to Earth and Venus, the characteristics of the newly discovered planet point to the chance it might have retained a certain amount of atmosphere.

That possibility and its closer proximity to Earth make the Venus-like Gliese 12 b ideal for further study.

“Follow-up observations with [NASA’s James Web Space Telescope] and future ground-based observations with 30-meter class telescopes for transit spectroscopy are expected to determine whether Gliese 12 b has an atmosphere and whether the atmosphere contains molecular components associated with life, such as water vapor, oxygen and carbon dioxide,” said Masayuki Kuzuhara, a project assistant professor of the Astrobiology Center in Japan and lead author of the study detailing the research that led to the discovery of Gliese 12 b.

The research was recently published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The team that made the discovery was led by the Astrobiology Center, University of Tokyo, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan and Tokyo Institute of Technology, which found and characterized the planet based on data from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, two multicolor simultaneous cameras and the three Big Island observatories: Subaru Telescope, Gemini Observatory and W. M. Keck Observatory.

Subaru’s infrared spectrograph, Keck’s second-generation near-infrared camera and the Gemini North telescope archive were critical in confirming Gliese 12 b was in fact a planet, ruling out the possibility it was the companion to Gliese 12, the cool red dwarf it orbits, in a binary star system.

“What makes this planet interesting is its size,” said Keck Chief Astronomer John O’Meara. “We have very few direct detections of planets we know to be around the size of Venus, even though [we] believe there to be many because the measurement is so difficult.”

The radius of Gliese 12 b is just 4% smaller than Earth’s. The exoplanet is also less than 3.9 times the mass of our planet.

The planet is so close to its red dwarf star that it only takes slightly fewer than 13 Earth days to complete its orbit. Gliese 12 b receives 1.6 times more radiation from its star than Earth does from the sun. Venus receives 1.9 times more radiation than Earth.

“Because of the distance to the planet’s host star, there is a possibility it has retained an atmosphere and possibly even liquid water on its surface,” O’Meara said.

Size is important. Jim Lyke, the lead for Keck’s Adaptive Optics Science Operations, said observations of other exoplanets show that smaller planets can remain rocky whereas those larger become gas giants, such as Jupiter and Saturn.

All factors — including the amount of energy the planet gets from its star and its atmosphere, if it has one — are keys to determining whether a planet could support life as we know it.

“We don’t know whether Gliese 12 b has an atmosphere, nor what the dominant gases are,” said Lyke. “Certainly, life can exist in environments where nitrogen and oxygen are not the dominant components — like submarine volcanic life.”

With only one planet where life has been confirmed, ours, studying life in the rest of the universe isn’t that easy and it’s hard to say which characteristics of Earth are necessary for life to appear.

O’Meara admitted that scientists have no idea what the exact recipe for life is, but they do have a fairly good sense of a range of atmospheric conditions that can support it. Lyke added that they do know how life works on Earth, so that’s what they try to find.

“Earth’s atmosphere was very different a few billion years ago, and so was the life on the planet then,” O’Meara said. “That said, we know how chemistry works, and so certain atmospheres/conditions just don’t allow for chemical reactions to work in the right way to make life possible.”

Even if they did observe different kinds of life, scientists might not recognize it.

In fact, one of the questions they want to answer is whether the conditions that support life on Earth are rare or not.

“As more and more rocky exoplanets are discovered and their physical properties are characterized, we will be able to apply statistics to likelihood of how many habitable worlds our galaxy has produced,” said Keck staff astronomer Greg Doppmann.

Until a “Terra Nova,” a new Earth or “Earth twin,” is discovered — where the conditions for life as we know it also appeared — the best examples astronomers can turn to are those “evil twins.”

They are planets with initial conditions similar to Earth but would have a hard time supporting life in our solar system today. That includes Venus and Mars and now Gliese 12 b.

The researchers think the newly discovered exoplanet is an “evil twin” because of the data they’ve gotten so far making it look more like Venus than Earth.

Even with a few of these perilous planets to study and our knowledge of how life on Earth works, there’s still much uncertainty about how stringent or lax conditions for life could be.

“We need to understand as much as we can about all planets to understand how planets like our own formed and evolved,” O’Meara said. “For Gliese 12 [b], we can eventually understand something specific: how a planet that is Venus-like in size could be similar or different to our own Venus.”

They can’t rule out the possibility that Gliese 12 b is more like Earth, with liquid water on its surface, but additional observations are necessary. That’s where the James Web Space Telescope and more powerful future ground-based observations will be needed.

Scientists are sure, however, that studying an exoplanet like Gliese 12 b in finer detail will shed light on what a life-friendly environment really looks like. They just had to find one first.

“These discoveries are special because humans have always explored — over those mountains, across that ocean and now looking out across the stars,” Lyke said. “These discoveries are the building blocks that will allow us to answer the question: are we alone?”

Gliese 12 b is another exoplanet that likely will eventually make its way into a new mass catalog of those discovered by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite in collaboration with W. M. Keck Observatory.

The catalog features 126 planets of a fascinating mix of types beyond our solar system. It contains the latest findings from the TESS-Keck Survey, the single largest uniform analysis of planets found by the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite.

Click here to find additional information.

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)