‘Last fishing village in Hawaiʻi nei’ in homestretch for long-awaited community center

At an outdoor pavilion with views of ocean waves and in the shadow of Mauna Loa, keiki in 4th through 8th grade learn reading, writing, STEM education and the historical significance of their rural home, which is carved into a wooden sign in all caps: “MILOLI’I LAST FISHING VILLAGE IN HAWAI’I NEI.”

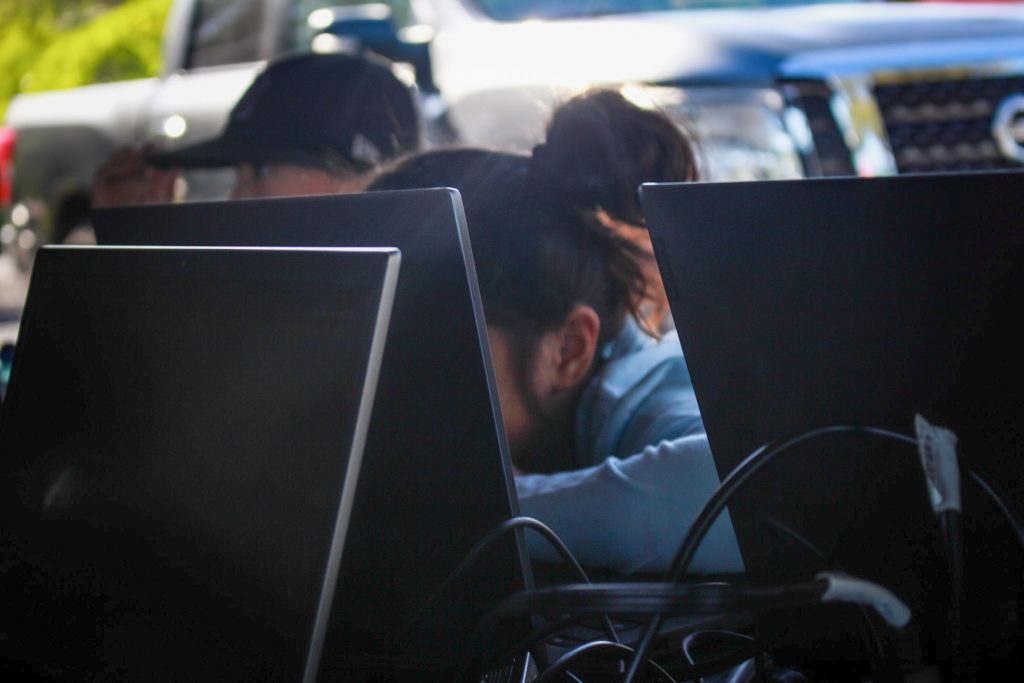

About 30 students are enrolled in the Miloliʻi branch of the Hawaiian public charter school Kua O Ka Lā, the school said. The branch with picnic tables for desks offers a mix of in-person and virtual curriculum, taught through the lens of Hawaiian culture and with community- and project-based learning.

For these Miloli’i kids, it’s the only opportunity to go to school close to home. The Big Island village is about 33 miles south of Kona, and a long drive from just about anywhere. The twisty country road to Miloli’i makes the travel time to the nearest school in Ho’okena or Kealakekua about an hour, and even longer on some days.

Lifelong Miloliʻi resident Leivallyn Kaupu remembers those hour-long bus rides as a kid. It is one reason she worked with others in 2012 to convince Kua O Ka Lā, located in Hilo, to establish a branch in the village. Kaupu was the branch’s first teacher.

For the past decade, the students who have attended the branch have had one-of-a-kind educational opportunities, such as manta ray diving and a culinary class. They also have an annual Lawai’a ‘Ohana Camp, where students learn traditional Hawaiian fishing methods in three days and participate in cultural-exchange programs in areas such as Tahiti.

The students and teachers are passionate about their school. They are happy. But there are a few problems: No permanent bathrooms. No kitchen.

Students must use porta johns and the teachers buy their own sanitizers and wet naps to provide to the children. Local families donate food from their kitchen. And often there are WiFi and technical challenges.

Kua O Ka Lā kumu (teacher) and lifelong Miloli’i resident Ka’imi Namaielua Kaupiko said these problems will be solved with the opening of the Miloli’i Enrichment and Historical Center.

The new community center, located just up the street from the outdoor pavilion of Kua O Ka Lā, is nearing completion — nearly 20 years after the late U.S. Sen. Daniel K. Inouye visited the rural Hawaiian village and launched an initiative to build it.

The project took so long due to a saga that includes a nearly lost federal grant, years of dealing with environmental assessments and permitting, code violations and changes in project leadership.

“This is what happens when the community doesn’t have control on projects that affect and impact them from the beginning,” Kaupiko said.

She estimates the facility will be ready to open for students and the community by next year.

The facility will be ready to open for students and the community by next year, said Melveen Kaupiko, the new project manager and cousin of Ka’imi Namaielua Kaupiko.

She says lessons have been learned from the experience that, in many ways, left the remote community feeling left out.

“The project began breaking ground on a bad note,” she said.

Melveen Kaupiko says she hopes the experience raises awareness about the importance of this unincorporated community of about 200 residents, of which many are related and whose families have lived there for generations. It’s also known for its aloha spirit, and for its ‘Ōpelu fishing technique and other ancient fishing practices.

Kaupu remembers the days when there were only five houses on the block, and when her family land extended beyond the now public access trails. She remembers the old gas station and grocery store that no longer exists, and the stories her kūpuna told her.

The village is along the seacoast, next to the fishing village of Hoʻopūloa whose houses were buried beneath lava during the 1926 Mauna Loa eruption. The village was selected for background in the 1962 Elvis Presley movie “Girls! Girls! Girls!” According to the Paʻa Pono website, the King stayed in the Magoon House, one of three existing structures that was identified in the 1970s for the “Hawaiʻi Register of Historic Places.”

But through its history and changes, Miloliʻi has been home for generations of tight-knit families.

That is why the teachers at Kua O Ka Lā and community members are pushing to finalize the decades-old project.

“We don’t need another house up the road. We don’t need more development up the road,” Kaupiko said. “What we need is a facility for our children and our community.”

The 3,200-square-foot community center just needs one last thing – a contractor to finish up the last needed touches.

The near-complete center includes enclosed and open-air classrooms, a historical library, kitchen, restrooms, workshop, parking lot with ADA stalls, water, Native Hawaiian landscaping and a photovoltaic power supply system, according to the Paʻa Pono website.

Pa’a Pono is a nonprofit group that has been involved with the project over the years. It aims to preserve and protect the cultural, historical and archeological heritage of Miloli’i.

When the project first started, it was a vision to have a space for community and children. But that vision was then burdened by outside obstacles. At one point, the entire project was estimated to be completed in 2015.

Kaupiko and Kaupu are optimistic the end is near and look forward to the day the students can flush a toilet.

“This is a good project,” Kaupiko said. “What we went through was a learning process. We are a small organization and had to learn about all the politics and permitting processes and had to fix it and move forward. And now we have everything we need to move forward.”

In the meantime, Kua O Ka Lā is fundraising for its programs, and a new vehicle, media center, marine lab and boat.

For more information visit www.kuaokala.org or email [email protected].