Two UH studies explain how and why erosion is threatening Waikīkī Beach’s shoreline

Researchers from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa published two studies that provide new understanding about how and why the iconic Waikīkī Beach on O’ahu is chronically eroding.

The studies, conducted by the university’s Climate Resilience Collaborative (CRC), will enable coastal managers and policymakers to better manage the coastlines of Hawaiʻi, according to a UH news release.

During a two-year study from 2018 to 2020 that included weekly surveys, a research team led by CRC Geospatial Analyst Anna Mikkelsen found the beach is primarily dominated by longshore transport, meaning that sand is moved from one end of the beach to another. This is contrary to standard beach models that predict cross-shore transport where sand is moved from nearshore to an offshore section of the beach.

“Another surprising finding was that we did not find any clear seasonal signal,” Mikkelsen said. “Instead of seeing high volumes of sand in summer, and low volumes in winter, we saw consistently increasing beach volume the first 12 months of the study and then erosion of the beach the following 10 months.”

The researchers discovered that the primary environmental drivers controlling the amount of sand present and the width of the beach include wave energy from south swell and trade-wind generated waves, and the water level.

In another study led by CRC Geospatial Analyst Kristian McDonald, the team surveyed the beach weekly between April and November 2018, a time that bracketed the Central Pacific hurricane season and the season of powerful southerly swells.

“We found a clear relationship between increases in south swell and beach accretion (gradual accumulation), and on the flipside, increased trade swell was associated with beach erosion,” McDonald said. “In addition, the hurricane activity of 2018 generally increased the surface area and volume of this beach due to the associated increase in south swell wave energy.”

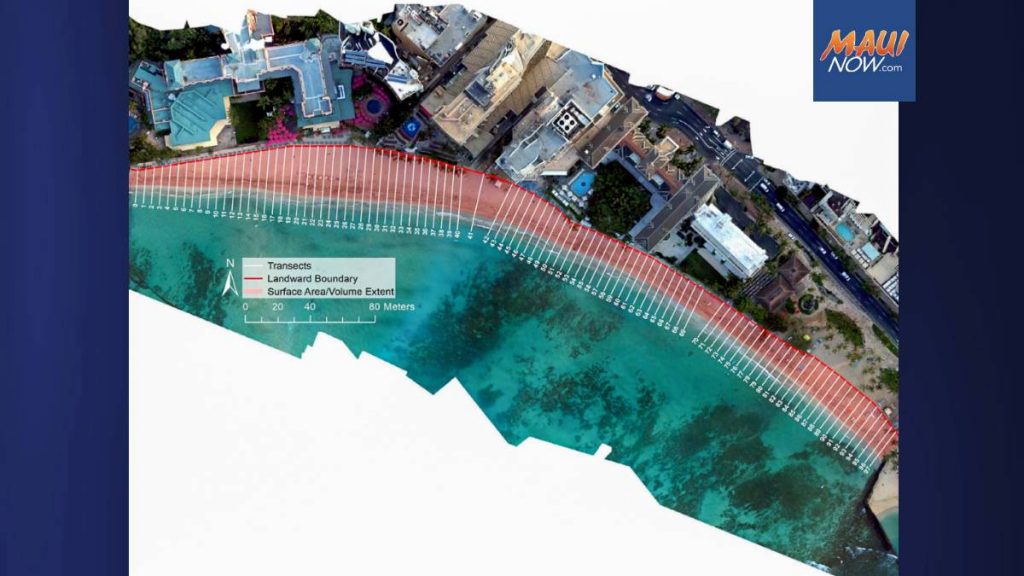

In each study, the researchers used consumer-grade drones, to conduct weekly surveys of Waikīkī Beach. Using photogrammetric techniques, they created 3D reconstructions of the beach, allowing them to derive surface area, volume, beach width and beach slope.

The team then compared these metrics with water level, wave conditions, wind and run-up to figure out what was most important in determining beach behavior, and whether trade-wind generated waves, south swell, Kona storms, high water levels or other conditions build or erode each section of the beach.

“Among the positive outcomes of this work is that it demonstrates that off-the-shelf consumer-grade drones can capture changing beach conditions at a very high resolution,” McDonald said. “These survey methods are relatively inexpensive and can be employed anywhere — even on remote shorelines — to inform communities and scientists of coastal dynamics and changes.”

Mikkelsen said: “In addition to gaining insight into where and how the Waikīkī Beach gets its sand, these studies help our understanding of how the beach may be impacted by sea level rise and changes in ocean conditions and provide information so that this resource can be effectively managed.”

The Climate Resilience Collaborative continues coastal monitoring of Oʻahu’s beaches. They are using drone survey techniques to document every beach on Oʻahu, which will provide a high-resolution baseline of the status of beaches today.

They also will get an idea of how the beaches change daily or weekly, and how they have changed historically by comparing satellite imagery dating to about 1990.

“Together, these two studies will help inform the next generation of our shoreline models and provide insights into short-term, seasonal and long-term changes our shoreline displays,” said Chip Fletcher, CRC director and interim dean of the UH Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology. “To effectively manage our coastline for ecological, societal and economic sustainability, we need this improved understanding of the behavior of our beaches and nearshore dynamics.”