Recovery frustratingly slow from 2018 Kīlauea eruption, but continues five years later

At least once a week, 68-year-old Deb Smith and her 69-year-old husband Stan hike 700 feet over black lava — often lugging groceries — to their house. It’s the same ordeal when they want to leave home.

While the elderly couple moved into a surviving home on property next to their original house, which was destroyed during the 2018 Kīlauea eruption, the road still has not been repaired.

Recovery efforts have been frustratingly slow on all fronts during the nearly five years since the catastrophic eruption ended in September 2018, leaving a big wake of destruction. About 8,448 acres of land, 700 homes and structures, several farms, public charter school Kua O Ka Lā, 32.5 miles of public and private roads, and 14.5 miles of water lines all proved to be no match for the molten magma that spewed for 124 days from the volcano’s Lower East Rift Zone.

“There is no playbook for how you recover from a volcanic eruption,” said County Councilwoman Ashley Kierkiewicz.

Recovery processes have been refined for natural disasters such as hurricanes, tornadoes, floods and wildfires, which happen more regularly in the continental United States. In many cases, there’s still something to recover. But lava destruction is different.

“Once lava comes, everything you knew is lost,” Kierkiewicz said. “It is literally under an 80-foot wall of new material.”

Hawaiʻi County officials say the total cost of infrastructure damage totals about $236 million, but little work has been done in this area. The County has instead focused much of its energy and resources in a housing buyout program, acquiring properties from residents impacted by lava.

About 3,000 Puna residents were displaced during the eruption, which started on May 3, 2018, and terrorized the area for more than three months. The Smiths are among the estimated 1,200 people who were directly impacted with the loss or isolation of their homes.

With federal and state aid, the county has received about $300 million:

- $127 million from FEMA for roads, water and park infrastructure

- $40 million loan from state to pay the 25% county match for the FEMA grant

- $107 million from the U.S. Housing & Urban Development for housing buyout program

- $20 million state grant for general disaster response and recovery

- $4.9 million from FEMA for ocean access and parks.

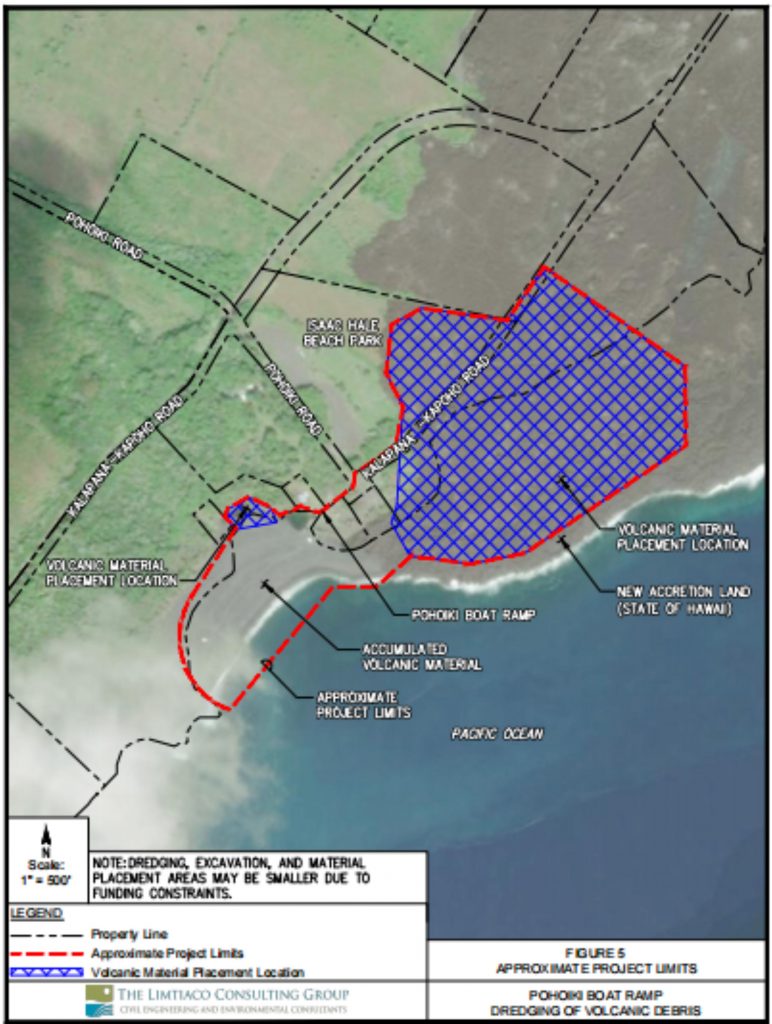

The State Legislature approved an additional $5.4 million that goes to the state Department of Land and Natural Resources for the Pohoiki boat ramp, which now is landlocked due to lava.

All grant funds designated for the County have been received and officially appropriated, meaning they have been accepted and integrated into the County’s operating budget.

County officials say they aren’t seeking additional funding at this time, and are focused on using the funding they have been given.

Of the 32.5 miles of destroyed roads, only 3.1 miles of county Highway 132 has been restored. The project was funded through the Federal Highways Administration’s disaster recovery grant. The road, along with an 1,100-foot section of Old Government Beach Road from Four Corners, reopened in November 2019.

Many residents like the Smiths are frustrated because there seems to be no plan for fixing the roads.

What’s the holdup?

Douglas Le, the disaster recovery officer for Hawaiʻi County, said the Federal Emergency Management Agency must complete an Environmental Assessment for road and waterline restoration along Pohoiki Road and Highway 137 before the county can use the federal funds for recovery projects.

But there now is hopeful news. On Tuesday, Le said the draft Environmental Assessment will be released on Aug. 3. It will be followed by a 30-day public comment period. A final report is expected to be finalized in September.

Water line restoration will follow.

The release of the draft Environmental Assessment, which started in January 2022, comes six months later than FEMA said it would be finished.

FEMA spokesperson Robert Barker said the the Environmental Assessment was drawn out because of the scale, scope and complexity of the work and potential impacts to natural and cultural resources around Pohoiki Road.

The scope of work changed multiple times, Barker wrote in an email, creating new revisions, altering the project’s footprint and its subsequent effects on natural and cultural resources in the area.

Deb Smith was skeptical about the news of the draft assessment, saying: “We’ve been hearing release dates since December and then postponements. This has been part of the unbelievable frustration.”

Kierkiewicz said she thinks roads is the highest priority in eruption recovery for Puna residents. Like the Smiths, many are hiking over lava to get to their homes.

“They’re stuck in limbo, like purgatory essentially, because their waiting to see if they’re going to get the roads back,” the councilwoman said.

Hawaiʻi County Mayor Mitch Roth said the County is ready to start working on roads once the environmental assessment is approved: “We’re impatient and the community is impatient.”

Roads covered under the FEMA grant are Lighthouse Road, Highway 137, Red Road and Pohoiki Road.

Out of the approximate 300 residents in the Vacationland/Kapoho Farm Lands subdivision, the Smiths are the only residents who have returned to live after the eruption. Deb Smith said there are other neighbors who return to check on their property that was isolated by the lava.

After moving seven times since the eruption, the Smiths found a path home when they decided to buy their neighbor’s 5-acre lot in 2021 that had portions of it untouched by the disaster although the main house burned down. It had a second residence that the couple was able to renovate.

The Smiths say they were told that the County, under Mayor Harry Kim’s administration, would repair the 700 feet of Lighthouse Road, which would’ve given them safe and regular access to and from their residence. However, that has yet to be done.

Since Lighthouse Road isn’t a legal access point, Deb Smith said they need the restoration of Highway 137 and Pohoiki Road.

“The County keeps delaying,” Stan Smith said. “I feel like we’re being lied to.”

Regarding ocean access and parks, the County estimated restoration would be at least $23 million four years ago. FEMA has only provided a $4.9 million grant. The State Legislature also approved $5.4 million specifically for Pohoiki boat ramp.

But that doesnʻt come close to the estimated $40 million that is needed for the project to dredge lava that flowed into Pohoiki Bay, landlocking the Pohoiki boat ramp that is vital to area fishermen and others.

What recovery efforts have been done?

The County’s housing buyout program began in 2021 with $107 million in community development block grants from the U.S. Housing & Urban Development. The program was for primary homes, second homes and undeveloped properties inundated or isolated due to lava.

From that funding, Le said the county spent $55 million toward direct assistance to households several years after the event.

Roth said the county has provided about $200,000 per family. The money, he added, has made a difference for some families being able to stay on island after losing everything in the eruption. But for others, it was not enough and they left.

The County received more than 300 applications for primary homes. Le said the County has closed on more than 275 homes with another 10 in the pipeline this month.

“We’re gearing up to begin acquisition of second homes in early 2024 and eventually will move on to the undeveloped properties,” Le said.

Deb Smith said she and her husband ultimately took a buyout on the property they lost.

“We knew we’d never get money back for it was worth so we had to let it go,” she said.

They still maintain the remaining two acres of fruit trees that were untouched by the lava.

A program called Revitalize Puna was created as a partnership of Pāhoa and area community members and the county to work together on recovery and resiliency. At quarterly meetings, updates are provided.

People also discuss and plan beach cleanups, painting businesses in Pāhoa Town and other events that bring residents together to support the growth of their community.

While it’s not getting the roads open tomorrow, Le said the projects help improve quality of life and the economy for the Puna community.

“To spend time together, to get to know one another to actually be working on projects together is really what we’ve been focusing on to rebuild trust in this recovery effort,” Le said.

The bottom line, Kierkiewicz said, is the eruption changed life in Puna forever. Some areas are completely buried under new lava and some residents have what looks like a wall of black lava in their backyard.

“Many people have left and some still want to do that dance with Tūtū Pele,” Kierkiewicz said.

Overall, the peace of mind and quality of life is disrupted for Puna residents impacted by the eruption five years ago.

“I can’t help but feel so much pain for my community,” Kierkiewicz said. “We can’t recreate what was lost.”

Editor’s note: This story is the first in a series about recovery efforts from the 2018 Kīlauea Eruption. We also have a story today about the lives of five Pāhoa residents affected by the lava and how they are doing now. Next week, we will explore more comprehensively the status of roads impacted during the 2018 flow and what are the plans to replace or repair them. And, we will have a Business Monday story about the Zen Garden, which opened in hard-hit Leilani Estates to help the community heal. Hawai‘i County posts regular updates about their recovery efforts at recovery.hawaiicounty.gov.

Other related stories to the 2018 Kīlauea eruption:

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)