Why Maunakea is sacred to many Native Hawaiians from their beginning to today

For years Kealoha Pisciotta, a Native Hawaiian practitioner, ocean advocate and a leader in the Maunakea protectors’ movement, has been visiting Hawaiʻi’s tallest mountain in prayer.

Sometimes she carries water to Pu’uhuluhulu, where she gently drips it over the rocks, whispering a prayer, tears in her eyes, stating an appreciation and recognition for an area known to hold the story of the beginning for Native Hawaiians.

Maunakea is the first-born mountain son of Wākea and Papa, progenitors of the Hawaiian race, and is symbolic of the piko (umbilical cord) of the island child, the Big Island, and that which connects the land to the heavens. Now, Maunakea towers above all else in the middle of the Pacific Ocean at 13,803 feet.

Pisciotta participates in annual solstice ceremonies and stands in aloha despite years of aggression and criticism for her stance on protecting the mountain, continuing to hold true to her belief that Maunakea is a sacred place.

“Our job is to have reverence for creation and when we don’t have reverence for creation, when we get stuck in subterfuge and politics and all those things we can see what happens — creation begins to unravel. Most of the sacred sites in the world are not only sacred to the people, but important to the earth,” she said.

And she’s not alone.

Maunakea is a place where Native Hawaiian cultural practitioners today engage in a variety of practices in Wao Akua, or the realm of the Akua-Creator — as did their ancestors for generations.

Ali’i and Kahuna (Hawaiian spiritual priests) often visited the mountain. There are stories of Gods and Goddess in ancient oral chants such as the Hawaiian creation story, the Kumulipo.

These handed down cultural practices are very much alive today.

Native Hawaiian practitioners can be seen gathering in a circle with their families and loved ones on Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea, the Sovereignty Restoration Day, or joining in dance and chant at the end of Merrie Monarch.

Meanwhile, speeding cars zoom along the mountain access road off Daniel K. Inouye Highway, astronomers and tourists come up and down the mountain, and sounds from the telescopes at the top interrupt the silence found in these rites.

Despite the surrounding noise, Native Hawaiian cultural practitioners stand in peace, to worship and show gratitude for the world’s second highest peak of an island. They bring balance and harmony to a place that doesn’t hold the same understanding for those outside of the culture. Some cars honk in support of the ceremonies as they pass by.

For Pisciotta, it holds her genealogical ties to her ancestors.

“We have a vertical cosmology, from the bottom of the ocean, the po, to the highest realm in the sky. The po is where creation and where Earth came out of and emerged from and when we pass we go back to,” she explained.

It’s these reasons and more that she’s been opening up about the various spiritual practices that take place there, and that are very much personal, in an effort to help others understand what the mountain is, and what it is not.

“Any person who is trying to claim it, control it, occupy it, is best described as subterfuge and a distraction to its sacred purpose and origin,” she said. “Like many other sacred sites they are sacred to life because they contain the majority of the biodiversity of the planet, which is needed to become resilient to climate change.”

Maunakea is also the island’s largest aquifer. It is home to Lake Waiau, which the Department of Land and Natural Resources has advocated for its protection. It is one of the highest lakes in the world and whose reason for existence is still unknown to modern scientists. There are also many native species that are endemic to the mountain, such as the the native Mauna Kea Silversword or ‘Ahinahina, and the Palila, an endangered bird.

During ceremonies, certain protocols take place, such as providing offerings or hoʻokupu (gifts) or water (wai), but there seems to be one underlying commonality that is often missed by outsiders — and that is to first ask for permission before entering the mountain.

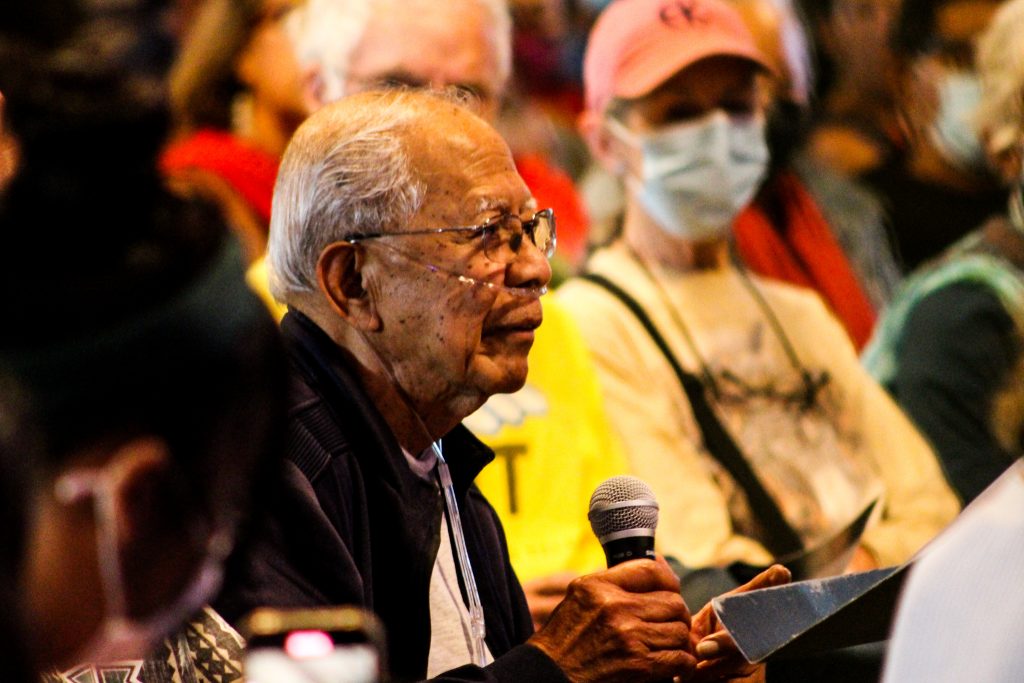

“You have to chant. You have to pray from Pu’uhuluhulu before you go up,” explained Kimo Pihana, 80, of Hilo.

Pu’uhuluhulu is located across from the Maunakea roadway where an ahu (shrine) can be seen from the highway.

“And then you stop at the visitor’s center and then you do another kahea (call) and ask permission,” he said. “When you leave the visitor’s center and go up the mountain, you have another area you have to ask permission to get to the summit and that area is not a place that many people know where it is. From there, the last place is the summit, from the very top is to akua — that made it the most sacred top of the mountain.”

Pihana was the first Maunakea ranger. He was recently featured in a University of Hawai’i article about his contributions to the mountain and said he started getting involved on the mountain to understand his own connection to the place.

“I was in search of the mountain,” he explained. “We are so fortunate as Hawaiian people to have the most sacred mountain and closest mountain to the heavens. Heaven on Earth, you could say. It’s the first place of the sunrise and the first nightfall of the setting sun.”

And, like others in the culture, he said right now there’s a need for balance there.

“It brought awareness to all of us to give that mountain some time to rest from human curiosity,” he said of the COVID-19 pandemic.

And, he added: “Without knowing the past, you risk the danger of not understanding the present and the future.”

It’s these reasons and more that many are drawn to the mountain, with thousands from around the globe joining the 2019 protests of the construction of another telescope. It is why people like Pihana and Pisciotta speak out about the culture and about the mountain’s importance, and to help others to feel the same love and appreciation for the one and only Maunakea.

As a result of the movement, the Hawaiʻi State Legislature created a new Maunakea Stewardship and Oversight Authority, which on July 1 began a five-year transition to take over from the management of the summit area from the University of Hawaiʻi.

However, cultural practitioners continue to voice their connection to the mountain and say as it stands that the “authority” remains with Akua and the people.

“Right now, they don’t have authority,” Pihana said. “It’s the Hawaiian people.”

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)