Hawaiʻi beachgoers can use smartphones to help researchers study endangered sea turtles

Hawai‘i beachgoers can now help federal scientists study the endangered sea turtles of Hawai‘i simply by taking a picture on their smartphone.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s “Honu Count” initiative launched in 2017, when it first asked “citizen scientists” to report honu (green sea turtles) with temporary alphanumeric markings on their shells.

The reports made by email or phone call helped NOAA researchers track honu movements throughout the major Hawaiian Islands and beyond.

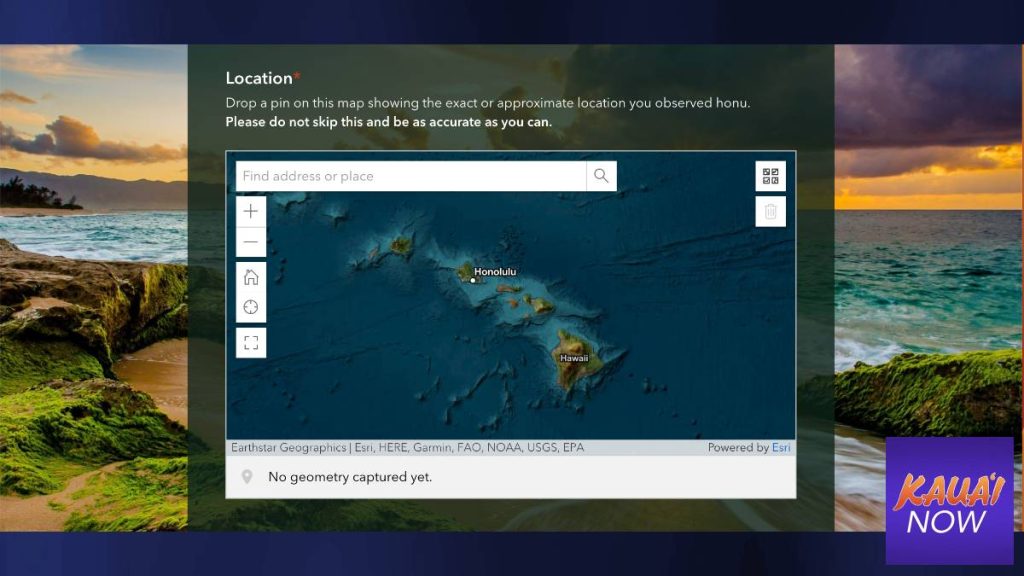

But public feedback indicated the system was inefficient, with some unsure if the Honu Count program was still active. It is. This month participants can now use a new mobile-friendly webpage to document honu sightings in a flash.

“We thought that this would be a really good way to make it easier for the public to help us collect the data, and then also easier for us to look at the data and analyze it more easily,” said research marine biologist Camryn Allen, who is with the Marine Turtle Biology and Assessment Program at the NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center in Honolulu.

Allen is a firm believer in the power of the Honu Count initiative. She thinks the public’s assistance may help solve some of the many scientific mysteries surrounding green sea turtles, including their famous habit of basking on Hawaiian beaches.

“Basking behavior is not something that happens worldwide,” Allen said. “It’s only in Hawai‘i and the Galapagos, so it’s not really well known why they do it. Of course, there’s a lot of hypotheses. People think that it’s because they are cold-blooded, so maybe they’re using it to warm up. Maybe it’s to avoid predators and maybe it’s to rest … We don’t know yet.”

She said he is hopeful the Honu Count will provide some insight.

“Is it the same individuals [turtles] all the time? Does it change by season or change by year? That’s really interesting information to find out,” Allen said.

Most visitors to Kaua‘i have seen a green sea turtle haul itself ashore on one of the island’s many beaches. Kaua‘i has always been frequented by many honu, according to Allen, and their local numbers have only increased in recent years.

Poʻipū Beach Park on the South Shore of Kaua‘i, where dozens of turtles bask every sunset, has become a popular destination for anyone eager to watch the charismatic reptiles.

Members of Mālama i nā Honu (Protect the Turtles), a statewide nonprofit organization affiliated with NOAA, ensure Poʻipū beachgoers maintain an appropriate distance from the turtles.

Debbie Herrera, Mālama i nā Honu’s volunteer education coordinator, says she and others have learned to identify individual turtles at Poʻipū Beach Park.

“Turtles are recognizable by their facial markings,” she said. “Those facial scales make a pattern (like a fingerprint for you and I) … Now that they are hauling out more and more during the day, we have been able to see those markings and are seeing returning honu showing up.

“In Hawai‘i, the honu will pick a beach that they kind of call their ‘home beach’ and return to it pretty regularly. We believe that’s what’s happening to the turtles at Poʻipū Beach during the day.”

Scientists don’t know why green sea turtle numbers are increasing on Kaua‘i. Some have suggested it’s due to shrinking nesting grounds in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, but Allen – who is tasked with investigating this angle – is not convinced.

“Yes, there is habitat loss in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, and it is nesting habitat that we’re losing,” she said. “What we’re not seeing yet is that any of the turtles are making the change to nesting from there to the main Hawaiian Islands.”

Most mature green sea turtles living around the main Hawaiian Islands travel northwest during the spring to reproduce at Lalo, or French Frigate Shoals, an atoll within the federal Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. Of that number, 50 percent of reproductive females would historically nest on an island called East Island.

However, a 2018 hurricane wiped the island off the map.

“Since then, the island has re-accreted, but it’s smaller than its original size. it’s about the size of three football fields,” Allen said. “It’s pretty small, which means it’s susceptible to high, high tides, or king tides, washing over the middle of the island. And the island is very dynamic … we were seeing nests that were laid early in the season starting to wash out in the later part of the season, because the sand was moving so much.

“Long story short, we’re concerned that the island in its current state is not quite a good nesting habitat.”

Researchers like Allen are concerned East Island is no longer an optimal nesting habitat for green sea turtles. But will the honu, which Allen describes as individualists, continue to lay all their eggs in this poor-quality basket? Or will they begin nesting elsewhere?

Allen is working on an answer. She’s now crunching preliminary data taken from a statewide effort that’s seen researchers perform ultrasounds on honu and equip them with satellite transmitters. But it’s very clear the turtles at Poʻipū Beach Park, which include immature individuals and males, are not nesting.

Green sea turtles, which can grow up to four feet long and weigh up to 350 pounds, can live for at least 70 years. Females don’t reach sexual maturity until 25 to 35 years old.

Green sea turtles are found throughout the world. There are about 3,000 nesting females in the Central North Pacific, the region that includes Hawai‘i.

“If you think about it, that’s not a lot of turtles, especially when they reproduce, on average, every four years,” Allen said. “And every hatchling that grows up to adulthood is usually one in 1,000. So essentially, when each female lays a nest every four years, that’s probably one hatchling every year that survives to adulthood.”

Scientists refer to sea turtle population sizes by nesting females, because it’s easy to count them when they come ashore to lay eggs. Federal researchers estimated there were 3,846 nesting females in the Central North Pacific in 2015. Assuming a one-to-one sex ratio, that means there were approximately 3,846 mature males.

However, it may not be wise to make that assumption. Sea turtles’ sex is determined by the temperature of the sand surrounding their fertilized eggs, and as global warming heats up beaches throughout the world, more and more honu may be born female. It’s yet another mystery Allen is investigating – her team is collecting blood from immature turtles to measure testosterone levels.

In the meantime, any beachgoer in Hawai‘i can help Allen and her colleagues by photographing any sea turtles they come across – although it’s imperative they keep a respectful distance of 10 feet on land or in water. For more safe viewing tips, click here.

If the turtle has alphanumeric writing on its shell, it’s important Honu Count participants record it. However, NOAA scientists may be able to identify some turtles by other indicators, even if the number is not entirely legible.

“If you just tell us it’s a turtle without a number, it’s not always helpful,” Allen said. “So focus on those turtles with numbers, maintain a safe distance and do not disturb them.”

NOAA’s new Honu Count Sighting Survey form can be found here.

Sponsored Content

Comments