Hawai’i Researchers Study Box Jellyfish Treatments

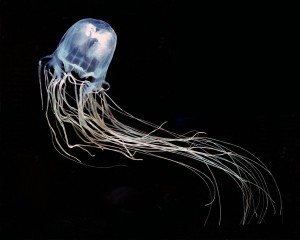

Yanagihara collecting jellyfish:

Dr. Angel Yanagihara collects Hawaiian box jellyfish (Alatina alata) at 3 am along Waikiki Beach, Honolulu, HI. Credit: University of Hawai’i.

Jellyfish stings no more? Hawai’i researchers have developed a collection of experiments that will allow the testing of first-aid measures used for box jellyfish stings.

The research paper was published recently in the journal “Toxins.”

More people die from box jellyfish stings on a yearly basis than they do from shark attacks. Scientists have even called the creatures among the deadliest on Earth. Still, more research on the most effective way to treat and manage jellyfish stings is necessary.

Researchers at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa developed the experiments, which allow the ability to rigorously assess the effectiveness of various treatment on inhibiting tentacle firing and venom toxicity, two aspects that a sting affects, causing the severity of a person’s reaction.

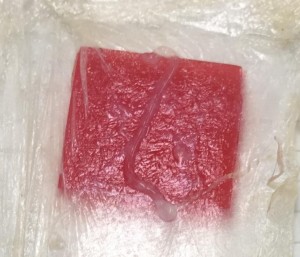

Skin blood argarose model:

Alatina alata tentacles stinging during a test of the tentacle skin blood agarose model. Credit: Christie Wilcox, © Yanagihara Lab/Department of Defense H922.

“Authoritative web articles are constantly bombarding the public with unvalidated and frankly bad advice for how to treat a jelly sting,” said Dr. Angel Yanagihara, lead author of the paper and assistant research professor at the UH Manoa Pacific Biosciences Research Center and John A. Burns School of Medicine. “I really worry that emergency responders and public-health decision makers might rely on these unscientific articles. It’s not too strong to point out that in some cases, ignorance can cost lives.”

Dr. Yanagihara and the research team have tested various methods, including the tried-and-true vinegar and hot water immersion, finding that they work on Hawaiian box jellyfish.

Another finding in the group’s study was in a new therapeutic, Sting No More solution, developed by Yanagihara with Department of Defense funding. Sting No More was developed to quickly treat stings in United States Special Operations Command combat divers. The solution inhibits venom directly.

Blood cells destroyed by stinging cells:

Blood cells destroyed by stinging cells create a clear halo around an Alatina alata tentacle (right) in the blood agarose model. Credit: Angel Yanagihara, © Yanagihara Lab/Department of Defense H922.

Yanagihara, aided by Dr. Christie Wilcox, a postdoctoral fellow at JABSOM, set out to test which first-aid measures actually help reduce the venom delivered when a tentacle stings or lessen the harm caused by venom that has been injected. But because box jelly stings can be life threatening, experimentation on people was out of the question.

“What we needed were innovative models that would allow us to test how different options might affect the severity of a sting without putting anyone at risk,” Yanagihara said. “So we designed a set of experiments using live, stinging tentacles and live human red blood cells which allowed us to pit first-aid measures against one another.”

The living sting model is comprised of human red blood cells suspended in an agarose gel and covered with lanolin-rubbed sterile porcine intestine, used as mock skin. Data in the study showed that Sting No More products and hot water were both effective treatments, with the Sting No More products acting faster and better.

“People think ice will help because jelly stings burn and ice is cold,” said Wilcox. “But research to date has shown that all marine venoms are highly heat sensitive. Dozens of studies, including our recent work, have shown that hot water immersion leads to better outcomes than ice.”

The new experimental models hope to allow for more rigorous testing of first-aid measure for venomous stings from other Cnidaria species, according to Wilcox.

“The science to date has been scattered and disorganized,” Wilcox said. “We strived to design methods that were straightforward and inexpensive, so that others can use them easily. The field has suffered from a lack of standardized, rigorous and reproducible models. Our paper outlines a way to change that.”

Currently, the study has only been used to test first-aid measures using the Hawaiian box jellyfish, however, researchers say they are working on seeing how the treatments will work for strings from other common Hawaiian species, including the Portuguese Man O’ War.