Insights: Is Hawaiʻi being left behind?

“Insights” are preliminary materials circulated by University of Hawaiʻi Economic Research Organization to stimulate discussion and critical comment. Views expressed are those of the authors. While “Insights” benefit from active economic research organization discussion, they have not gone through formal academic peer review.

Throughout the United States, a number of regions that once thrived struggle to adapt as their economies change.

These “left-behind places” share a common pattern: a dominant industry stops growing, productivity stalls and incomes stagnate.

Local economy doesn’t necessarily collapse; it simply fails to keep pace as the rest of the country moves ahead, leaving residents with declining relative living standards and frustration with their economic situations.

These conditions eventually fuel what scholars call “geography of discontent” and “revenge of the left-behind places” — communities where mix of slow growth and fading opportunity translates into declining civic trust, sharper political polarization and growing skepticism toward economic development itself.

These dynamics often reinforce themselves.

When growth stalls, public investment erodes and private confidence weakens, making it harder for regions to adapt. At the same time, frustration can fuel political reactions that undermine the very institutions needed to support recovery — slowing growth further and amplifying the sense that opportunity lies elsewhere.

In other words: without careful intervention, it could get worse.

Hawaiʻi at first glance does not fit the image of a left-behind region. It is desirable, expensive and globally recognizable. Yet the economic data tell a more complicated story.

When we look past Hawaiʻi’s high prices and focus instead on long-run growth and purchasing power, and the trajectory for both factors, the islands increasingly resemble regions well-recognized to have fallen behind.

This blog walks through the key evidence.

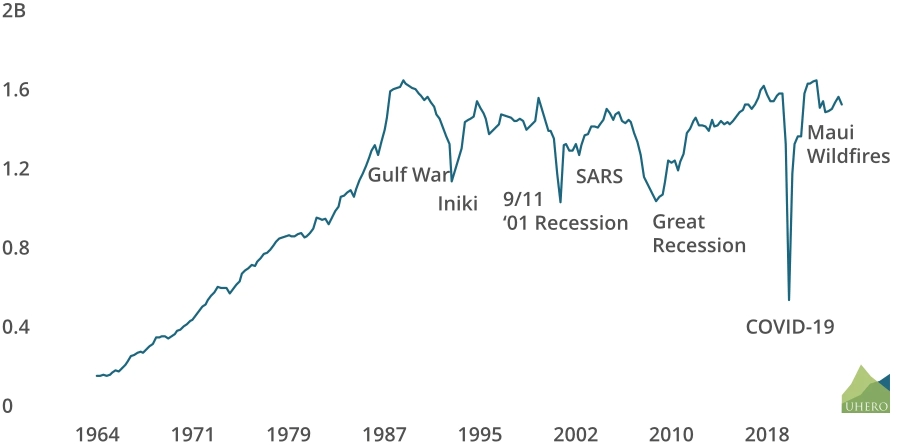

Tourism: A long boom followed by three decades of stagnation

Stagnation begins for most left-behind regions when their anchor industry stops growing. That industry in Hawaiʻi is tourism.

Tourism thrived after statehood, rising rapidly through the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. But by about 1989, the expansion stopped.

Tourism spending has since fluctuated around the same level, interrupted only by major global or local shocks such as the Gulf War, Hurricane Iniki, the Asian Financial Crisis, 9/11, SARS, the Great Recession and COVID-19.

There is no sustained upward trend after the late 1980s.

This matters because tourism is Hawaiʻi’s economic backbone. When it stopped growing, the broader economy struggled to grow.

That dynamic is a hallmark of left-behind regions: the dominant industry matures and the economy plateaus with it.

Real Tourism Spending, 1964 to 2025 (constant 2024 dollars)

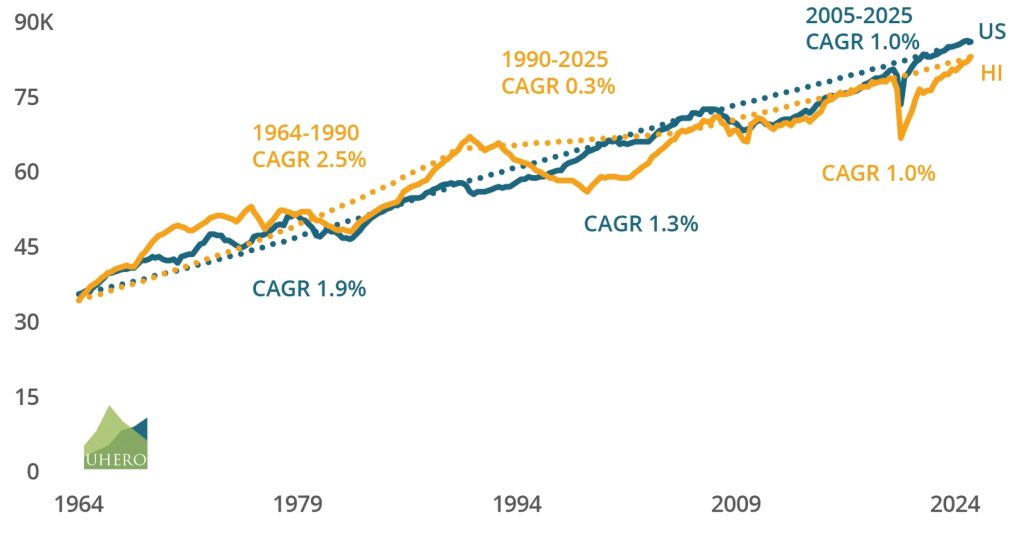

Hawaiʻi’s economy hasn’t kept up, especially once we account for prices

If we look only at real gross domestic product per capita — adjusted for national inflation — the story is familiar.

Hawaiʻi surged ahead of the mainland United States through the 1960s to the 1980s. The “lost decade” of the 1990s hit Hawaiʻi hard. But after 2000, Hawaiʻi roughly matched U.S. growth, although from a lower level.

Hawaiʻi does not look as good as it once did in that view, but it also does not look like a left-behind place. It appears to be a place that suffered a setback in the 1990s, then broadly kept pace afterward.

This picture, however, leaves out a crucial detail: Hawaiʻi’s high cost of living.

Even when prices are stable, a high price level erodes the real value of every dollar earned. A state can appear to keep pace in nominal or inflation-adjusted gross domestic product yet still sit well below once local purchasing power is taken into account — and even tiny price increases chip away at income growth.

To see a more accurate picture, we adjust Hawaiʻi’s gross domestic product per capita for its consistently higher cost of living using University of Hawai‘i Economic Research Organization’s Consumer Price Index-based regional price parities.

Once we make that adjustment, the story changes dramatically.

Price-adjusted data show that Hawaiʻi has not kept pace since the early 1990s at all. The mild recovery after the lost decade continued into a mild recovery from the Great Recession, and another after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hawaiʻi’s real purchasing-power-adjusted gross domestic product per capita, as a result, has barely grown for more than 30 years, diverging steadily from the rest of the country.

Real Gross Domestic Product Per Capita and Compound Annual Growth Rates, Hawaiʻi and the US, 1964-2024

In other words: Hawaiʻi’s economic stagnation is not a recent development.

Once we account for local prices, the “lost decade” did not end in the 1990s; it is ongoing. This is the clearest quantitative evidence that Hawaiʻi is becoming a left-behind economy.

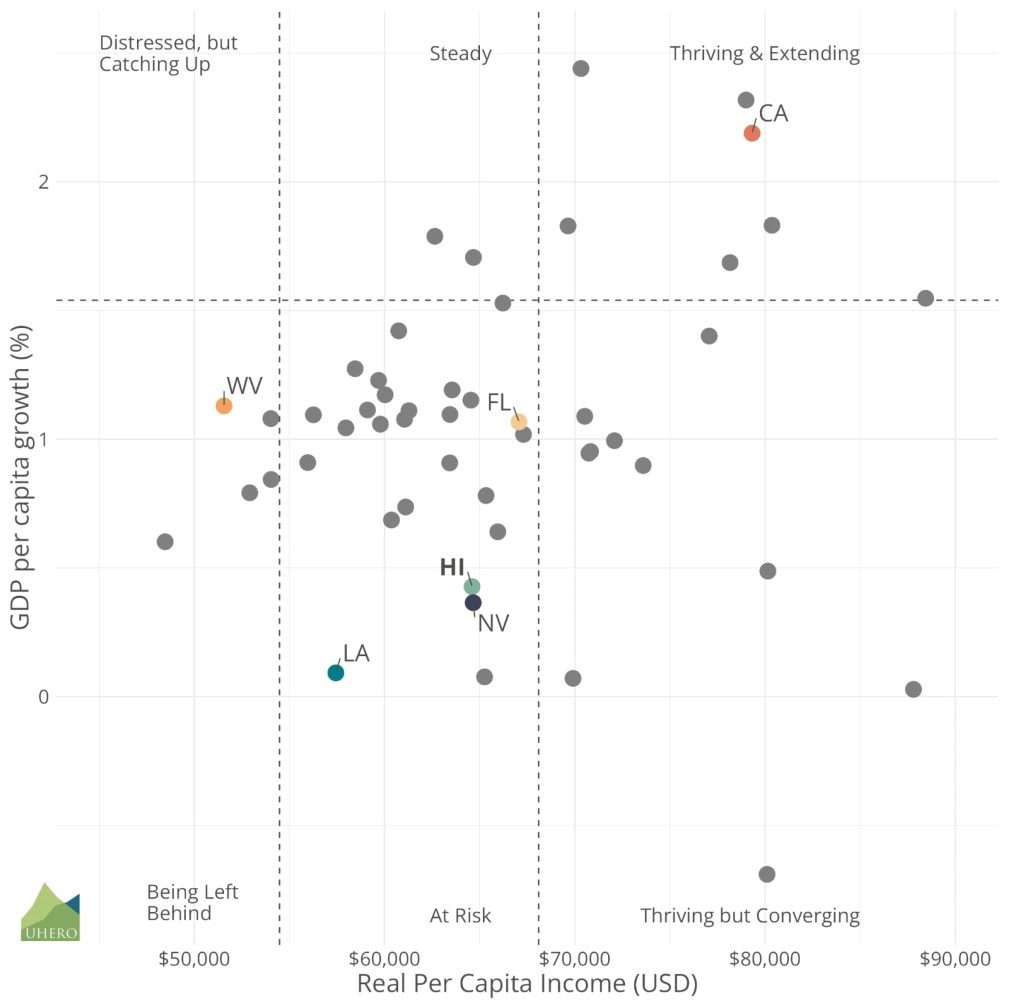

How do states compare?

Economic distress is defined in federal policy using thresholds based on per capita income and unemployment.

Under U.S. Economic Development Administration’s criteria, a region is considered economically distressed if its per capita income is less than 80% of the U.S. average or its unemployment rate is at least 1 percentage point above the national rate for 24 months.

These thresholds determine eligibility for certain federal development programs, including support for Economic Development Districts.

Real gross domestic prouct per capita compound average growth rate by state 2008-2023, and incomes 2023

So how does Hawaiʻi compare to other states when we use this criterion?

Without adjusting for prices, Hawaiʻi looks “at risk.” It’s not especially strong, but it’s not among the poorest-performing states.

Growth is low, but local per capita incomes are only slightly below the national average. As might be expected, Hawaiʻi sits near Nevada and other middling performers. If this were the full picture, we might conclude that the state is underperforming but not fundamentally distressed.

We categorize this group as “at risk.”

When incomes are adjusted for local prices, we also adjust the distress threshold proportionally. Without this adjustment, states with low incomes but also low prices would appear much better off despite being included in the regulated definition of economic distress.

The federal benchmark — per capita income less than 80% of the U.S. average — is defined using nominal incomes, which already reflect that distressed states tend to have lower living costs.

If U.S. Economic Development Administration’s 80% nominal-income rule is a reasonable benchmark for identifying economic distress, the same states should continue to be classified as distressed after adjusting for prices.

Because price adjustment compresses income differences throughout states, however, we also raise the threshold — from 80% to 90% of the U.S. average — to reflect this narrower range and provide a fair comparison.¹

In the adjusted picture, Hawaiʻi’s regional price parities-adjusted income drops significantly because high prices reduce purchasing power.

Adjusting for prices doesn’t change Hawaiʻi’s growth rate much because — while the state is already expensive — prices are steady.

Nonetheless, Hawaiʻi’s long run growth rate is among the lowest in the country.

Regional price parities-adjusted incomes in other states often are adjusted upward, reflecting their much lower prices. When measured on a cost-of-living–adjusted basis throughout all states, Hawaiʻi’s relative position shifts sharply downward.

Hawaiʻi does not look like a high-cost version of Colorado or Washington with the adjustment. It looks like an even slower-growth version of West Virginia.

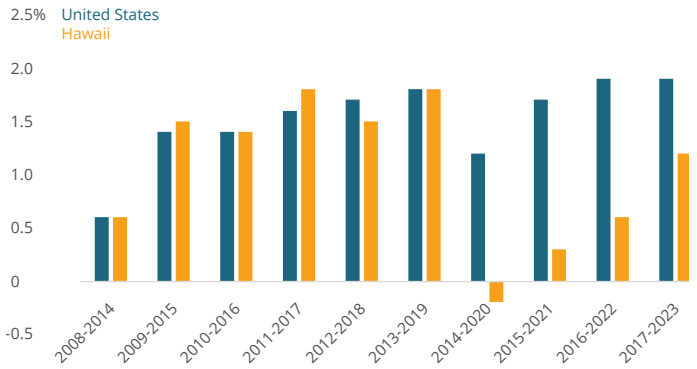

Why this matters

Many narratives about Hawaiʻi focus on its cost of living: housing prices, groceries, energy, child care and taxes.

Those are serious issues. But high prices alone don’t make a region left behind.

Regional price parities-adjusted long run average growth rates adjusted for local price levels, U.S. and Hawaiʻi, Rolling 7-year periods, 2008-2024

Many of the most expensive regions in America — Seattle, Boston, New York, the San Francisco Bay Area — are also among the most productive and highest-income.

What distinguishes Hawaiʻi is not only that it is expensive. It is that incomes and productivity have not kept up, and this has persisted for decades.

When productivity stagnates for this long, regions typically experience slower wage growth, reduced economic mobility, increased outmigration, rising political discontent, difficulty sustaining public services and declining resilience to shocks.

These are all features of left-behind places.

Hawaiʻi is not simply expensive. It has been economically stagnant more than 30 years, and the high cost of living masks the depth of that stagnation.

Key implications are:

- Cost-of-living policies are necessary but not sufficient. Lowering prices helps residents but does not fix the underlying trajectory.

- Productivity and diversification must rise. The tourism plateau limits the growth path unless new high-value industries emerge.

- Stagnation is self-reinforcing. If wages do not keep pace with opportunities on the mainland, outmigration will continue even if prices fall.

- Addressing the “left-behind” dynamic is urgent. The longer growth remains weak, the harder it becomes to reverse.

Is Hawaiʻi being left behind?

Data suggest it is, though not in the same way as traditional left-behind regions.

The high cost of living might even mask these structural weaknesses and extent of Hawaiʻi economic decline. Adjusting for those costs reveals a large and growing gap between Hawaiʻi and nation overall, akin to that of some of the most economically distressed states in the country.

To change course, Hawaiʻi will need to confront the structural sources of its low productivity growth and create space for new economic opportunities beyond tourism.

The alternative is continued stagnation and outmigration — a trajectory that already reshaped the state more than many realize.

¹ In a separate paper (currently in progress), we estimate empirically that the price-adjusted threshold for economic distress is about 94.6%. Using a 90% cutoff here is therefore a conservative adjustment.

These “Insights” were written by University of Hawaiʻi Economic Research Organization assistant professor Steven Bond-Smith and graduate research assistant Erich Schwartz. They focus on a key theme from the comprehensive report “Beyond the Price of Paradise: Is Hawaiʻi being left behind?”

Sponsored Content

Comments

_1770333123096.webp)